|

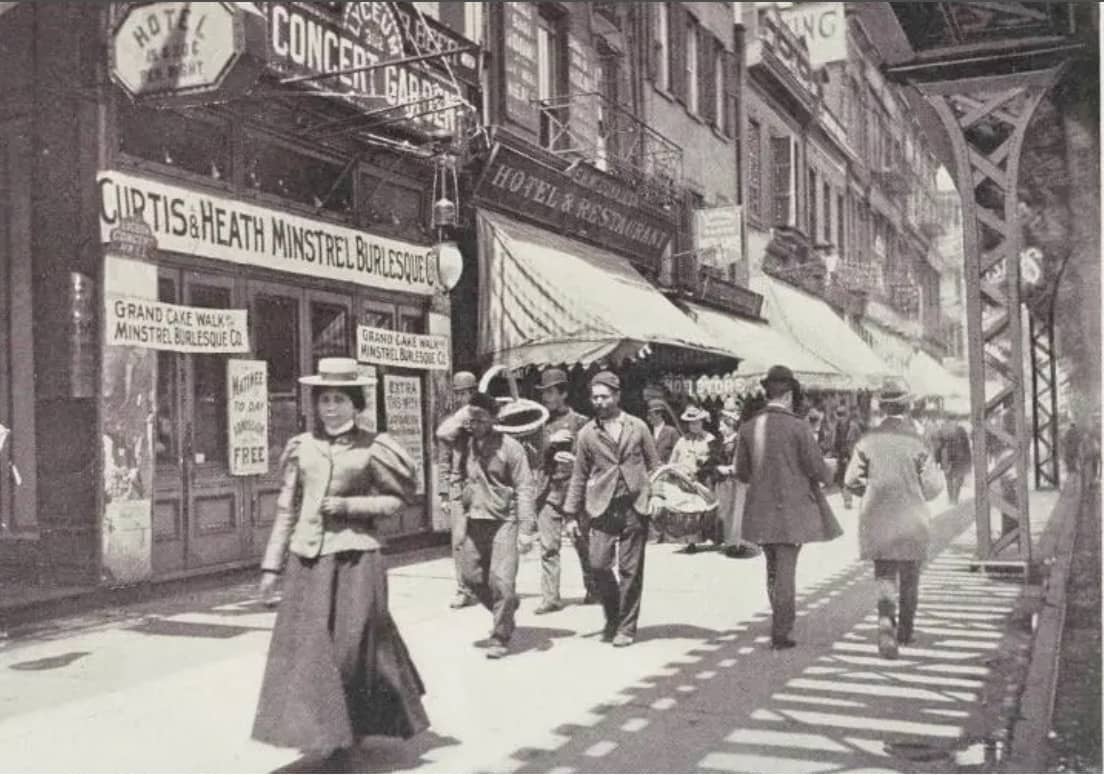

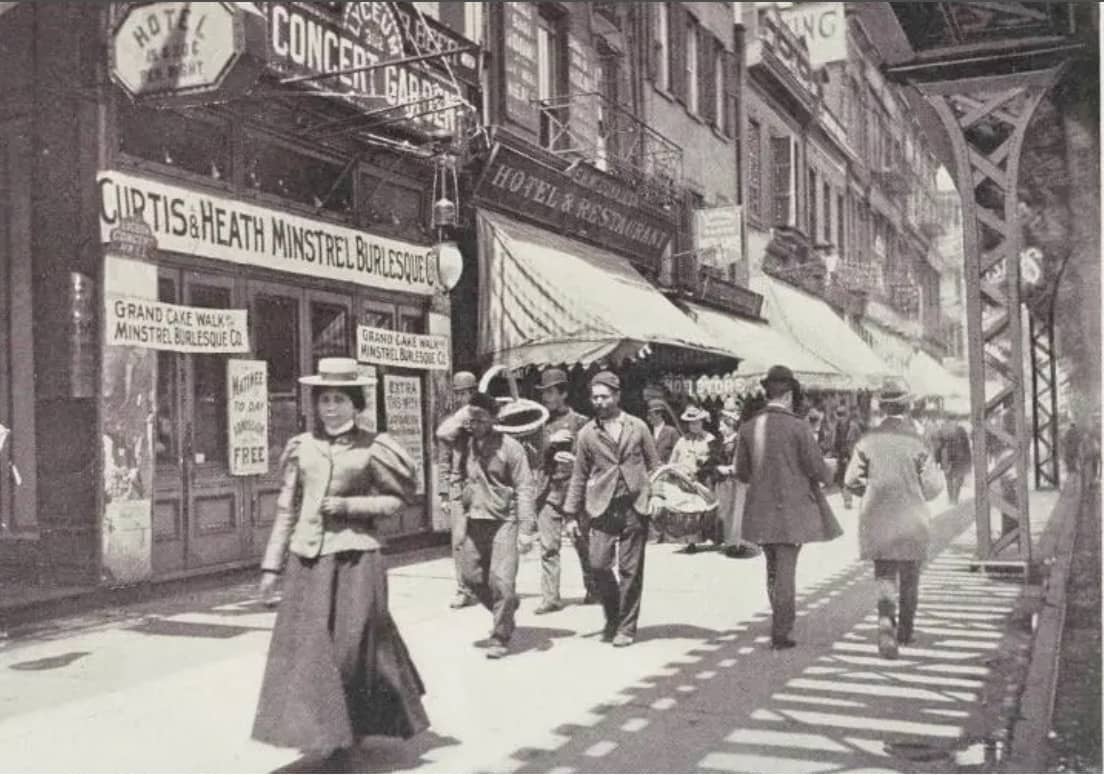

| Bowery, NYC, 1910 |

I recently remembered this piece which I put up at Criminal Brief in 2009 and thought it was worth repeating. Frederic DeWitt Wells was a magistrate in New York City. In 1917 he published a book called A Man in COurt, trying to explain the legal system to the layman. Remember that people in those days didn't get weekly doses of legal dramas on TV. MOst of the book is didactic and not very interesting today, but the first chapter, describing a session of Night Court still has the power to fascinate.

Before we get to that, a couple more things about Wells. In 1913 he wrote a letter to the New York Times about a woman who had stored all her family’s belongings in a storage warehouse. She wound up in the hospital for the insane. Her daughter Mary Shriver, paid fifty cents a month for the next two years to keep up the fee on the storage. As the Times reported: “All of her worldly possessions were in the trunks, but because of the fact that they were stored in her mother’s name and because of the latter’s mental condition, there was no way in which to obtain their release. She sought relief in the courts, with the result that, through the law’s delays, she lost her employment and her condition has been rendered even more precarious.” Because of Wells' letter an anonymous person donated the $200 needed to get Schriver's property out of storage.

Two months after the stock market crash in 1929 Justice Frederic DeWitt Wells was hit by a car in Manhattan and died at age 56.

A NIGHT COURT

In the Night Court the drama is vital and throbbing. As the saddest object to contemplate is a play where the essentials are wrong, so in this court the fundamentals of the law are the cause of making it an uncomfortable and pathetic spectacle.

The women who are brought before the Night Court are not heroines, but the criminal law does not seem better than they. It makes little attempt to mitigate any of the wretchedness that it judges; in many cases it moves only to inflict an additional burden of suffering. The result is tragedy.

The magistrate sits high, between standards of brass lamps. His black gown, the metal buttons and gleaming shields of the waiting police officers, the busy court officials behind the long desks on either hand tell of the majesty of the law.

In front of the desk but at a lower level is a space of ten or twelve feet running across the court-room in which are patrolmen, plain-clothes men, detectives, women prisoners, probation officers, reporters, witnesses, investigators, and lawyers. Beyond in the court-room a large crowd is on the benches. There are witnesses, brothers and sisters, friends of the prisoners waiting to see whether they go out through the street entrance or back through the strong barred gate seen through the door on the left. Also there are the “sharks” waiting to follow out the released prisoners, to prey upon them as the circumstances may favor; and a number of curiosity seekers watching intently. For them it can be nothing but a morbid dumb show, for they are so far from the bench that not a word of the proceedings could be heard. Only once in a while the shrieks and imprecations of a struggling hysterical woman as she is hurried out of court can enliven the scene.

Fortified with a letter of introduction to the judge and a disposition that will not be too easily shocked at seeing conditions of life as they actually exist, the spectator may find his way past the policeman at the gate in the rail. It clicks behind him ominously and he wonders whether he will have difficulty in getting out. Finally through clerks and officials who become more kindly as they learn he is a friend of the judge, he is seated in a chair drawn up beside the bench. The magistrate is a hearty round-faced man who seems almost human in spite of his gown and the dignity of his surroundings. The court looks different from this point of view and he may easily watch the judicial enforcement of the law supreme.

The organization of these courts is simple. There are not many rules or technicalities. The judges are patient, hard working, understanding, and efficient. The trouble is with the laws they are called upon to administer: Laws which are as absurd, as farcical, and as impracticable as the plot of the lightest musical comedy.

At first the visitor can hardly understand what is going on. A pale-faced man is in the witness chair, on his left a bedraggled little woman is standing before and below the judge, her eyes just level with the top of the desk. Clerks are coming with papers to be signed: “commitments,” “adjournments,” “bail bonds”; others are trying to engage his attention. In the meanwhile the case proceeds.

“I inform you,” says the judge to the woman, “of your legal rights, you may retain counsel if you desire to do so and your case will be adjourned so that you may advise with him and secure witnesses, or you may now proceed to trial. Which will you do?”

She murmurs something. She is pale-faced with sullen eyes, drooping mouth, an over-hanging lip. A sad red feather droops in her hat.

“Proceed,” says the judge; and to the policeman who is called as a witness, “You swear to tell the truth, the whole truth mm-mm-mm–you are a plain-clothes man attached to the 16th Precinct detailed by the central office, what about this woman?”

“At the corner of Fifteenth Street and Irving Place,” says the witness, “between the hours of 10:05 and 10:15 this evening I watched this woman stop and speak to three different men. I know her, she has been here before your Honor.”

“What do you say?” the judge asks the woman. She is silent.

“What do you work at?”

“Housework, your Honor.”

“Always housework; it is surprising how many houseworkers come before me.” She smiles a sickly smile.

“Take her record. Next case,” says the judge. Outside it is a cold sleeting night in early March.

“Witnesses in case of Nellie Farrel,” calls the clerk.

Nellie Farrel stands before the desk beside a policeman; she is tall with fair waving hair. She must have been pretty once; even now there is a delicate line of throat and chin. But her eyes are hard and on her cheeks there are traces of paint that has been hastily rubbed off. She looks thirty; she is probably not more than twenty.

A callow youth, who seems preternaturally keen, swears that on Thirteenth Street between Fifth Avenue and University Place the woman stopped and spoke to him; and he tells his story as though it were learned by rote.

“Do you know the officer who made the arrest?” the judge asks him.

“I do.” A suspicion arises that there may be an interest between the witness and the policeman.

A dark-haired, smooth-faced woman who is standing by the prisoner says: “Your Honor, she’s my sister. I’m a respectable woman, my husband is a driver. I have three children. It’s disgrace enough to have the likes of her in the family. If you’ll give her another chance I’ll take her home with me; my husband is here and he’s willing.” The accused looks down piteously.

“Discharged on probation,” says the judge, and the family go out.

“That’s the third time that’s happened to her,” whispers a clerk. “Every time the sister comes up like a good one.”

A horrible old woman with straggling gray hair, shrivelled neck, and claw-like hands grasps a black shawl about her flat chest. “Mary,” says the judge, “thirty days on the island for you.”

“Oh, your Honor, your Honor, not the workhouse. Oh, God, not the workhouse,” and she is borne out screaming and fighting and invoking Christ to her aid. The judge turns and says in explanation, “an old case, an example of what they all may come to.”

A dark-haired little French woman is brought in with crimson lips, bold black eyes, and expressive hands. A detective testifies that he went with her into a tenement house on Seventeenth Street west of Sixth Avenue. Charge: Violation of the Tenement House Law.

“Qu’importe,” says the woman. “I go in ze street. I am arrested. I stay in ze house. I am arrested. I take ze room. I am arrested. Chantage—Blackmail. C’est pour rire.”

Who are these women who are brought in a crowd together? One of them older than the rest is a foreigner plainly dressed in black silk with a gold chain. She does not seem particularly evil, but rather respectable. The others are in long cloaks or waterproofs hastily donned and through which are glimpses of pink stockings. They have hair of that disagreeable butter color which speaks of peroxide. There has been a raid on a west-side street of a house of ill repute. Some testimony is given and the older woman, the “Madam” is held in bail for the action of the Grand Jury while the rest are held for further evidence. The judge tells us there will probably not be enough testimony and they will be released in the morning. But unless bail is found they will spend the night in cells.

A nervous, excited woman comes in—two policemen are with her. She has been arrested for disorderly conduct on Sixth Avenue near Thirty-first Street. She has been fighting with a man who has also been arrested and taken to the men’s Night Court. Hers is a hard, tough face of the lowest type.

“Why should you try to scratch the man’s face? What did he do?” the judge asks. “Is he your husband?”

“My husband, your Honor? Yes, I guess you can call Al that. We lives up town and when I went out he says to me, ‘Hustle, kid, you got to hustle, the rent’s due and if you don’t get the money I’ll break your neck.’ The slob won’t work. Well, a night like this you couldn’t make a cent and I only had half a dollar and I wanted to get a bite to eat. I hadn’t had a thing since four o’clock, and then I met Al going down Sixt’ Avenue an’ he tries to swipe me fifty cents off me and I was that wild I wanted to tear him. I’m sorry; I guess it was my fault. I don’t want to see him jugged, so please let me off, your Honor, and I won’t make no trouble.”

“Take her record,” said the judge, “and hold her as a witness against the man.”

A string of women are brought in for sentence who have been having finger prints taken in the adjoining room. The judge proceeds to impose sentences according to the previous records which are shown. Some of the women are those who have passed in front before. The little bedraggled woman with the red feather has been arrested seven times in sixteen months. Another has spent eight weeks in the workhouse out of a period of seven months; another has been sent already to the Bedford Reformatory; another has been twice to houses of reform. Before the judge gives his sentence he refers the prisoners to the probation officer, who talks with them in a motherly way.

After talking with the little prisoner she addresses the judge. “She says its no use, your Honor, she does not want to reform—it will not be worth while to put her on probation.”

“Committed to the Mary Magdalene Home,” says the judge, and the name brings a startling surmise as to what He of Galilee would have said.

The foregoing is only a typical session of the court. Night after night, from eight o’clock until one in the morning, the scene is repeated. The moral effect and its reaction upon those who conduct the proceedings—the judges, officers, and the police, cannot but be deplorable; the evil done to those forcibly brought there could not be over-estimated.

Substantially the law is that the women may not loiter in the streets nor solicit in the streets, or in any building open to the public. They may live neither in a tenement house nor in a disreputable house. The law makes it a crime for the women to walk abroad or stay at home. Their existence is not a crime, but only in an indirect way the law makes them outlaws. Anyone wishing to prosecute or persecute finds it easy to do so. The worst enemies of these unhappy women are to be found, curiously enough, among both the best and the most evil people in the community. The unspeakably depraved are the men who, either as procurers, blackmailers, or the miserable men who live on a share of their earnings. The excellent people who oppose any remedial legislation which might relieve the situation, seem equally responsible for the present condition, however well-intentioned they may be.