What good is a wet blanket against a cannonball?

What good is a wet blanket against a cannonball?

We'll come back to that one.

Before I decided to try my hand at fiction, I spent a fair amount of time pursuing the tenure track as a "professional historian." I got my MA, published scholarly articles, and strongly considered going on to earn my PhD.

|

| An actual blanket soaked in water |

During that time I encountered all manner of apocryphal, anecdotal stories concerning the great and small, the wise and the foolish, the lucky and the unlucky. Some of them were just what they seemed: terrific stories, and nothing more, with little in the way of available evidence to support them. Others were well-documented with all manner of primary sources to serve as bonafides.

The ones that drove me nuts as a practicing historian were the ones I'd find in secondary sources, with primary sources to detail how exactly the incident in question came to be recorded, laid down for posterity, if you will.

|

| Self-explanatory |

Oh, and I should have clarified this earlier for those of you non-historians playing at home: when I say "primary," I mean a source who either witnessed or otherwise participated in the historical events being discussed. "Eye witness" stuff. A journal entry. A letter. A videotape. A blog entry/social media entry. "Secondary" means literally everything else: Someone at a remove of one or of several people in the communication chain. For example, if you're writing about your grandfather's experiences growing up in Seattle in the 1950s and using his diary as a reference, the diary is "primary," and your writing about it, "secondary."

The primary source can also be in certain instances, secondary, as well: like if your grandfather writes movingly about his father's experience as a young immigrant coming through Ellis Island a generation before the grandfather himself was born, your grandfather's account, even though it's related in a source that is mostly "primary" in nature, is in this case, "secondary."

Clear? Hope so.

With that clarifying digression out of the way, back to the type of history that drove me nuts as a professional historian.

Back when I was still working on my Master's (we're talking nearly thirty years ago now), I wrote a paper about the role of the Hudson's Bay Company in the exploration and settlement of the Pacific Northwest. I even got the chance to present said paper at a scholarly conference. I still have a copy. It was good work, solid analysis. I was pretty satisfied with it.

The only problem is that I had a series of events I wanted to include in my paper, but couldn't. Because I could only find secondary sources about them. These events culminated in a bloody confrontation between agents of the Hudson's Bay Company and members of a Native American tribe called the S'Klallam, in Dungeness Bay, on what is now Washington's Olympic Coast, bordering the Straits of Juan de Fuca on July 4, 1828.

I'm talking about the now infamous Cadboro Incident.

The Cadboro was a schooner built in England in 1824, bought by the Hudson's Bay Company, and sent to support HBC activities in the Oregon Country in 1826. The Cadboro will be important later.

As with many things, the causes of the so-called Cadboro Incident were many. The inciting factor though? Really just a single one. A man. a fur trader named Alexander MacKenzie.

MacKenzie was, like so many HBC employees in the Northwest at the time, a Canadian of Scots heritage who came out to the Oregon Country already an experienced fur trader. That's not to say he was good at his job, just that he had experience at it.

He was also possessed of a terrible temper and fiendish disposition. And of course, he viewed Native Americans as inferiors. This much shows in his actions.

In the Spring of 1828 MacKenzie was on a trading mission, having led a party of four men and a woman who walked from Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River, up to Puget Sound, and all the way to the territory of the S'Klallam (who were widely considered hostile to whites at the time). Once there, he hired two teen-aged S'Klallam boys to carry his party in a couple of canoes to several points in Puget Sound, then across the Strait of Juan de Fuca to Vancouver Island, and back to their point of origin at what is now Port Gamble, Washington.

Things did not go well. MacKenzie beat and cursed the two boys when they asked for their agreed-upon pay. That night his party was attacked and all four men killed, with the woman (presumably a Native American) taken captive. It was assumed the attack was undertaken by elders of the S'Klallam, the tribe to which the two boys MacKenzie had so abused belonged to.

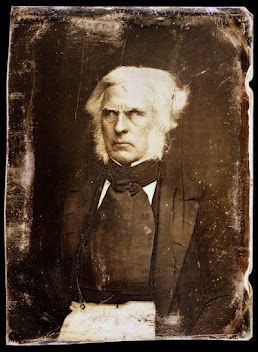

|

| The formidable Factor: John McLaughlin |

When Chief Factor John McLoughlin, ranking HBC employee at Fort Vancouver, got wind of the attack, he dispatched the Cadboro to punish the killers and negotiate the return of their captive. After all, it would never do for local tribes to think they could kill HBC traders with impunity. Not only was it bad for business, there was also considerable outrage among the white denizens of the Oregon Country (British and American citizens alike) that Native Americans had dared attack a party of white men.

Long story short: the Cadboro arrived at the S'Klallam village on modern day Dungeness Bay, where it rendezvoused with a detachment of sixty-some HBC employees under the command of HBC trader Alexander Mcleod. After linking up, the HBC representatives entered into negotiations for the release of the kidnapped woman. The Cadboro carried three cannon onboard. In the middle of these negotiations, all three cannon opened up on the village.

By the time the smoke cleared the village was leveled. Forty-six of the tribe's canoes were destroyed. Twenty-seven people, men, women and children, were killed. The captive woman was "rescued" and a portion of MacKenzie's trade goods were retrieved. The Cadboro returned to Fort Vancouver by sea, and Mcleod's expedition returned south by the overland route, but not before burning another S'Klallam village for good measure.

Mcleod expected a warm welcome upon his return to HBC Headquarters. Instead the same superiors who had dispatched his force and schooner in the first place were put off by the actual extent of the punishment his men and the cannon of the Cadboro visited upon the S'Klallam. Apparently being too violent when meting out retribution was also considered "bad for business" by the braintrust running the HBC. It later cost Mcleod a promotion to Chief Factor.

I have found considerable evidence supporting the facts as related above regarding this incident. The problem? They're all secondary sources. I've looped in colleagues still in the business over the years: folks with tenure, who know the field, and they have had no more luck than I in tracking down any primary sources about the so-called Cadboro Incident.

So I couldn't justify using it in my paper all those years ago. And it's a shame, because this is a story that deserves to be told. And retold. And remembered.

Of course, I write fiction these days…

Oh, and the question above about wet blankets and cannonballs? The S'Klallam, not at all understanding the destructive power of a cannon, soaked their blankets in water and hung them from the walls of their homes in an effort to defend them from the cannonballs of the HBC.

Let that one sink in.

See you in two weeks.