|

| Photo by Shane Leonard |

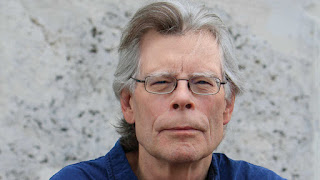

Once upon a time, an underpaid, overworked schoolteacher from Maine wrote some books. A lot of books. He loved horror, but he also knew that might limit him. So, on horror he put one name, using another for decidedly not-horror books, with one exception. As his first published novel was a story about a teenage outcast with telekinetic powers, you can tell which type of story he liked to write.

The novel was Carrie by Stephen King. But the other books, three dystopian thrillers and a noir story about a guy who ain't givin' up his house, didn't really fit the King mold. Not when he had a major streak of successes with his first four novels: Carrie, Salem's Lot, The Stand, and The Shining. All these are not just horror classics but, in the case of The Stand and The Shining, literary masterpieces the snooty MFA-prof-having-dirty-thoughts-about-student set cannot bring themselves to acknowledge. Maybe King will have to die first for them to accept him. Except he's already rejected him, so it'd be like inducting the Sex Pistols into the Rock Hall.

But what of those other books? King originally took his mother's maiden name and the name of someone he knew and combined them into "Gus Pilsbury." Now, I have a hard enough time selling books as "Jim Winter" (a Star Trek reference only one person in 30 years ever figured out. Captains April and Pike would be so disappointed.) Stephen King is an easy-to-remember name. Gus Pilsbury makes me think of biscuits or cinnamon rolls or... Oh, look. Laura Lippman (another market-friendly name and one, like King, gracing her birth certificate) has a new one out!

King picked up on this. After Carrie and Salem's Lot, he wanted to see if he could do it again. So out went "Gus Pilsbury" and in came "Richard Bachman," complete with a fake bio and a picture of one of his editors as the author photo. King even listed a religion for Bachman. (Rooster worship, for the curious.) As Bachman, King had four books in the trunk. Actually, he had five, but he wasn't happy with one until he took it out in the 2010s. What were they?

Rage - Inside the mind of a mass shooter. When King wrote this, he was a schoolteacher and one not that far removed from the high school angst and anger that power this story. Also, mass shootings were rare. Then came Columbine. The shooters admitted in their journals they took inspiration from this story. So King decided to kill his own novel. But how is it as a novel? Meh. There are little King flourishes in it. His catch phrase, "friends and neighbors," shows up. But it's a lurid trip into the mind of a teenager who loses it with fatal consequences. You can still get it in older copies of The Bachman Books, but otherwise, no recent reprintings. It will probably stay that way for decades to come.

The Long Walk - King embraces his inner Ray Bradbury, then gets dark. Really dark. Every year, a select group of teenage boys participate in the Long Walk, starting at the US-Canadian border and following US 1. In theory, they could make it all the way to Key West, but no one can stay awake that long. Why do they do it? The Prize. In a gambit King will repeat in The Running Man, the boys risk getting shot in order to get the Prize, implied to be more money than God has and never having to worry about food, housing, health care. It's a sham run by a militaristic figure called "the Major." The America depicted in it could be taken straight from The Handmaid's Tale. As a non-horror novelist, King is finally finding his groove.

Road Work - Probably my least favorite of the Bachman books, but I understand where it comes from. King wrote this as his mother was dying. A single mom who had to keep as much of her struggle from her kids as possible, she was the center of his universe, at least until he met Tabitha Spruce, aka Tabitha King these days. The novel is a bitter, angry story about a man who resent eminent domain long before it was abused to put in shopping malls and overpriced housing. In this case, a fictional Midwestern city is adding a bypass which will go through where his job and his house both sit. Rather than move and take the money, he sits on his hands and ignores the warnings. He loses his job and his wife, and it doesn't end well when the construction crews finally show up.

The Running Man - Probably the best known Bachman book. Soon after King was unmasked as Bachman, he sold the film rights. It became an Arnold Schwarzenegger action romp. King wasn't happy with the movie, but both are fun dystopian stories. In the book, Killian is a black man who is a grinning, sleazy figure arranging for the poor to participate in fatal gameshows to keep the masses entertained. Had they followed the book, one might picture Laurence Fishburne channeling his inner Marvel villain in the part. In the movie, Killian is the host, played by Richard Dawson of Family Feud fame. In both, Ben Richards kills him off, only more directly in the movie. While it has the dark dystopian themes of the earlier Bachman books, it's probably the most fun to read.

Thinner - Really, a thinly disguised Stephen King book, and the one that unmasked him. Billy Halleck runs over an old Romani woman and is cursed by her son to grow ever thinner. At first, this is great for the overweight Halleck, but soon, he starts resembling a concentration camp survivor. This hasn't aged well, but is the novel which blew his cover. While the references to Gypsies and their culture have not aged well, there's no mistaking Portsmouth, NH is really Derry. It reads and looks like a King book. Yet sales of the book suggest the next Bachman book scheduled, Misery, would have broken through and put "Bachman" on the bestseller list. Instead, King got an inspiration for The Dark Half.

The Regulators - King's not even trying to hide it now, especially since the four-volume Bachman Books collection had been out for years. It's a sequel to Desperation, which is not my favorite King novel. There's a meta-story here where Bachman, whose bio now says he died of cancer in 1987, wrote the sequel without meeting King or reading Desperation. It doesn't really work, and King puts Bachman to bed for close to two decades.

Blaze - King calls this a trunk novel. It isn't even dystopian, nor is it a thinly disguised King novel. When Stephen King did not know what kind of writer he wanted to be, he penned this noir novel about a slow-witted, brutal man nicknamed Blaze. Blaze does some horrible, evil things, yet he isn't evil. He is a victim of circumstances. Ironically, King had even less faith in this story than he did Carrie, but once he dug it out, he rewrote it in American Typewriter font to recreate the vibe he had when he wrote the original. It's probably the best of the six books, but maybe because he wrote it with an innocence one eventually loses writing over time.