|

| A young Karl Gutzlaff |

I talked a while back about the opium trade in China, run by Western "trading companies" like Jardine-Matheson and Russell & Company, who smuggled and sold opium (then illegal) all up and down the coast and rivers of 19th century China. And how that led to two Opium Wars, which eventually forced the Chinese (who lost) to make opium legal. And Christianity. Both legalizations merged in the person of the one and only Karl Gutzlaff (1803-1851), missionary, journalist, translator...

What do you do with a person like Karl? He started out as a missionary when he was 23, sent to Java by the Netherlands Missionary Society in 1826. (Karl was German, born in Pomerania.) He left them after 2 years, and spent the rest of his life in the mission field as an independent operator, earning his living in a variety of ways, some of which were highly unorthodox. Please remember this: Karl Gutzlaff was never "officially" affiliated with any organized church ever again.

He moved around a lot: from Macau, to Singapore, and eventually Hong Kong. He was a superb linguist, speaking/writing Chinese, Thai, Cambodian, Lao, and perhaps Japanese. He translated the Bible into all of these languages and wrote dictionaries for at least three of them. He also - and this is VERY key - married a very wealthy English missionary, Maria Newell, who died in childbirth within a year, leaving him all her money. In 1834, he remarried, to missionary Mary Wanstall, who at that time ran a school and home from the blind in Macau. (She died in 1849, and Karl remarried, one last time, in 1850 to an English woman in England.)

|

| Karl, in native dress |

In 1840 his Chinese translation of the Bible was published. It would be the text adopted by the leader of the Taping Rebellion, God's Chinese Son Hong Xiuquan (and I hope to write about that wildly improbable man some day). It was also the year that the First Opium War began, and Gutzlaff translated for the British throughout, assisted at the negotiations for the peace treaty, and got an official government position afterwards for his trouble. NOTE: He did not work for free.

In 1844, he set up his own training school for native missionaries and an organization - the Chinese Union - to send them out. It succeeded well enough that Gutzlaff went on a hugely popular European fund-raising tour from 1849-1850. Back in China, though, things were nowhere near as rosy as Gutzlaff proclaimed: Most of his native Chinese "missionaries" were criminals and/or opium addicts who faked their conversion figures, taking the Chinese Bibles that Gutzlaff had given them to distribute and selling them back to Gutzlaff's own printer, who then resold them to him. (Jessie Gregory Lutz, Opening China: Karl F. A. Gutzlaff and Sino-Western Relations, 1827-1852, p. 276) A huge scandal erupted, forcing him to return to Hong Kong in 1851. It was still going on when he died in 1851.

Despite the scandal, Gutzlaff's legacy was wide-spread and varying. His idea of native missionaries and foreign missionaries speaking the native language, wearing native dress, living as the natives did, caught on, and was continued through the founding of the China Inland Mission under Henry Hudson Taylor. This (now the Overseas Missionary Fellowship, a/k/a OMF International) became the primary missionary organization in China.

|

| Harry Parkes, Consul |

|

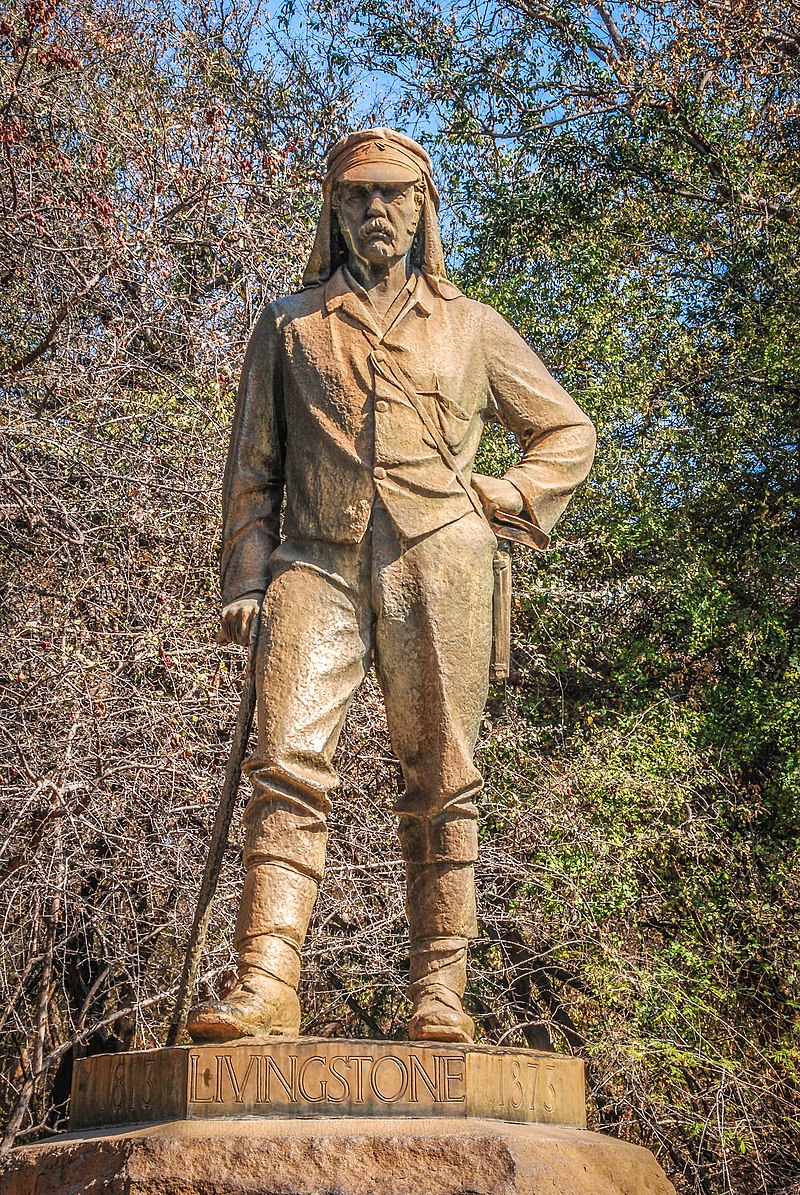

| "Dr. Livingstone, I presume." |

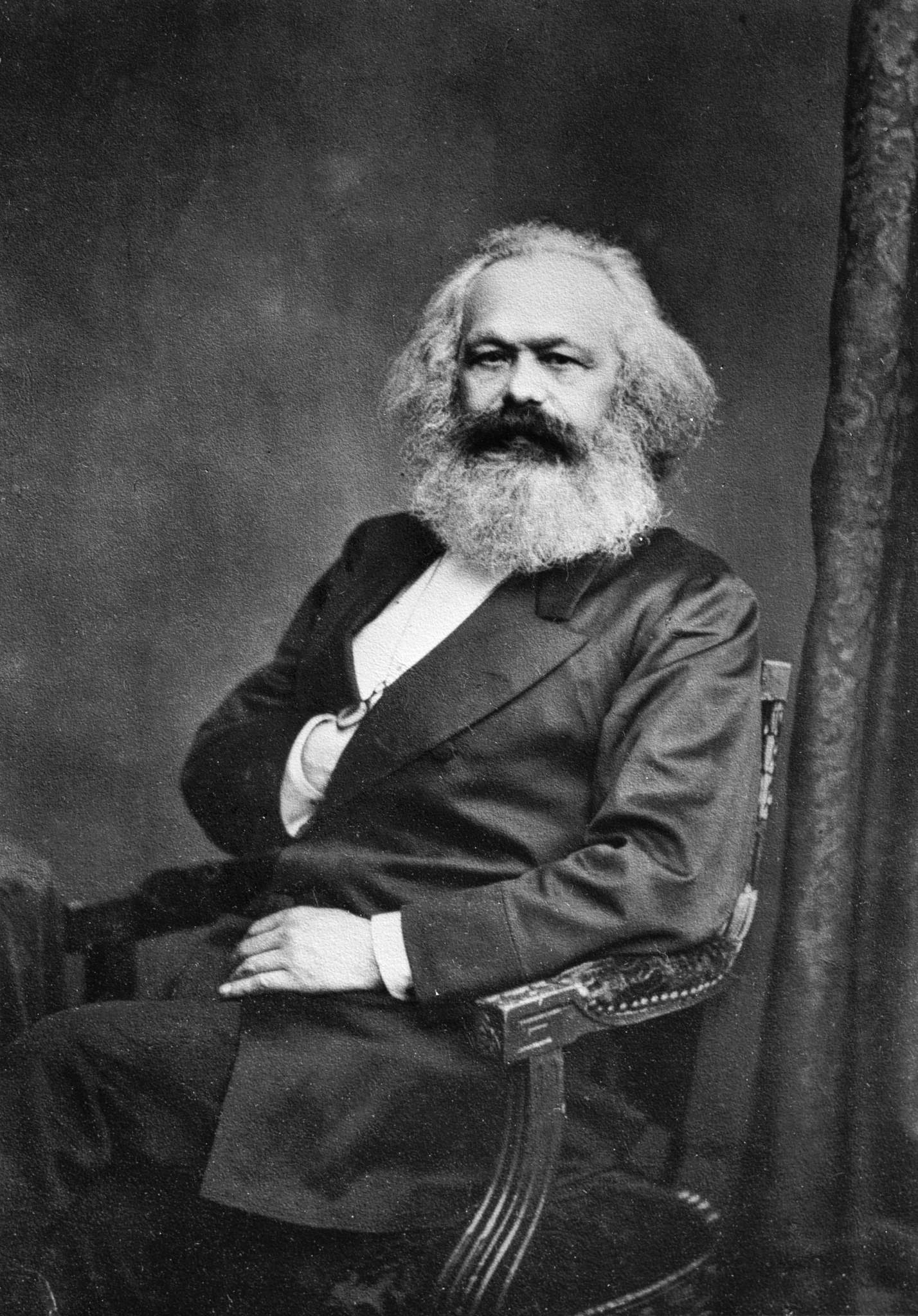

Remember the European fund-raising tour that Gutzlaff went on to raise money for the Chinese Union? Karl Marx went to hear him speak in London (David Riazonov, "Karl Marx on China", 1926). He also read Gutzlaff's many writings, which became sources for Karl Marx' articles on China for the London Times and the New York Daily Tribune in the 1840's and 1850's, all of which are anti-imperialist and anti-religion.

(Alas, I have searched for, as yet in vain, for a direct written-in-Karl-Marx'-hand connection between Gutzlaff and Marx's well-known statement, "religion... is the opium of the people." All I can say is, it was written in 1843, nine years after Gutzlaff's "Journal of Three Voyages..." was published. Who knows?)

|

| "HK Central Gutzlaff Street sign near Wellington Street" by Wenlensands - Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: HK_Central_Gutzlaff_Street_sign_near_Wellington_Street.JPG#/media/File |

A very influential man. And also, in many ways, a mystery: a profoundly earnest missionary, who would use any means that came to hand, including the opium trade. A man of great pride and presumption, who was convinced that the Chinese were inferior to Europeans, and yet was the first to train (or at least try to train) native missionaries. A great linguist, who made sure he got paid very, very well for his translating work. As you can see above, there's a street in Hong Kong named for him. There's his writings. And there's the image of him, in his twenties, handing out Bibles from the back of the opium ship as the traders are handing out opium from the front... Karl, Karl, Karl...