I had just begun.

When I was two

I was nearly new . . .

Now We Are Six

A. A. Milne

Next week, on Tuesday September 17, SleuthSayers celebrates its second anniversary. Since that date falls on a Tuesday Terence Faherty and I (who share that day on a bi-weekly basis) were asked to kick off the festivities. We pondered how best to do this, and ultimately decided to let SleuthSayers speak for itself. (Err, ourselves!) So this week and next week you are getting our nominees for memorable articles of years one (today) and two (next week).

When Terry and I decided on this approach it was our goal, going in, to identify three to five articles for each month of each year, articles that when viewed in the context of each twelve month period would show what SleuthSayers is all about. Terry is still working on the next installment, but I have to say at the beginning of mine that, as is evident below, I failed. There are too many great articles out there to whittle a year into 60 or fewer entries. In fact, there is a good argument that each of us should have just thrown up our hands and said “hey, gang, go back and read, or re-read, them all.”

The list set forth below is therefore both too long and too short. I've had recurring worries as to the articles not included, and all I can say is that my list (and, I suspect, Terry’s next week) is highly subjective. Ultimately I tried to identify articles that were timeless -- that will always bring out a smile or a nod of agreement from the reader. If I missed a favorite, well tell me -- that's what the Comments feature is for.

So, herewith, SleuthSayers, the First Year: September 17, 2011 through September 16, 2012. And, as a result of the wonders of our blogger program, together with a good dose of tedious rote work on my part, all of the titles set forth below have click-able links that will get you back to the underlying article. So discover, re-discover, and have fun.

So, herewith, SleuthSayers, the First Year: September 17, 2011 through September 16, 2012. And, as a result of the wonders of our blogger program, together with a good dose of tedious rote work on my part, all of the titles set forth below have click-able links that will get you back to the underlying article. So discover, re-discover, and have fun.

SleuthSayers -- The First Year

SEPTEMBER 2011

Plots and Plans -- John Floyd starts the ball rolling with the first posting on Sleuthsayers.

Should classic novels be re-written for modern tastes? What happens when we start down that slippery slope. Dale Andrews looked at this in Rewrites.

Desperately Seeking Detectives --Writing characters with real-life flaws? Janice Law took a look at this, with particular emphasis on Alice LaPlante’s excellent Turn of Mind, a story narrated by a character descending into Alzheimer.

OCTOBER

The Crime of Capital Punishment -- Leigh Lundin spins the history of gallows, “old sparky,” and capital punishment generally over the years.

Different Strokes -- John Floyd (who has more published stories than many of us have read) gives pointers for writing and submitting mystery stories.

Speaking of Lists and Series -- Fran Rizer expounds on the best mystery stories of all times, and some other matters!

Do Writers Write to Trends? Should they? -- Elizabeth Zelvin offers advice concerning whether trends should be followed or ignored by budding authors.

The Death of the Detective -- Janice Law discusses authors’ decisions to kill off their detective. And what do you do when later you change your mind?

My Uncle the Bootlegger -- Louis Willis’ colorful recollections of growing up in the hills and hollows of the east Tennessee back-country.

NOVEMBER

Ideas Are Us -- At a loss concerning how to start a project? Jan Grape tells how she finds ideas for books and stories.

Digitally Yours -- Neil Schofield take a tongue-in-cheek look at how computers worm their way into each of our lives.

When the Grammar Cops Comma Calling -- John Floyd takes a look at the trouble we can get into when we drop a comma in the wrong place. As the title suggests, be ready for some humor in this one.

Twin Peaks -- Leigh Lundin turns back the way-back machine for one more look at one of the strangest mystery shows ever to grace network television.

My Name is Fran and . . . -- Fran Rizer offers up a primer on one of the things she does best -- writing cozies.

Wellerness -- What is a wellerism? Generally it’s a cliche applied with humorous effect. Want some funny examples and a discussion of the origin of the word? Check out Leigh Lundin’s column.

Flying Without a Parachute -- R.T. Lawton takes us inside one of his police investigations. And tells a neat story while he is at it.

Metaphor Hunting -- Louis Willis celebrates Thanksgiving and at the same time offers some of his favorite literary metaphors -- some from fellow SleuthSayers.

When We Were Very Young -- Why do we write? When and how did we take that first step that sent us down this road? David Dean ruminates on all of the above.

Digging Up Old Crimes -- Attending the fourteenth annual Biblical Archaeology Fest in San Francisco Rob Lopresti discusses mysteries covered in presentations on archaeology and early Judaism.

DECEMBER

How Can a Martian Wax VentuVenusian? -- Dixon Hill offers up an insightful and at times humorous look at the differences between male and female audiences.

Editorial Crimes -- Liz Zelvin gives us a fine discussion on finding the right voice for fictional characters.

Mr. Swann Toasts Mr. Wolfe -- Guest columnist (and sort of the grandfather of SleuthSayers) James Lincoln Warren gives us the written remarks he delivered when his novella Inner Fire was awarded the 2011 Black Orchid Novella Award.

Do You See What I See? -- Jan Grape uses the holiday season as a catalyst for a discussion on getting dialog right.

At the End of Your Trope -- Rob Lopresti presents a great discussion of tropes. What are tropes? As Rob points out they are “a catalog of the tricks of the trade for writing fiction.”

to e or not to e -- R.T. Lawton discusses taking the leap into e-publishing.

What’s in a Word? -- Fran Rizer takes the first of several SleuthSayer looks at how the English language grows.

Crime Family -- David Dean shows us that sometimes our criminal antagonists are fashioned on someone, well, . . . close to home.

Hugo and Shakespeare -- Leigh Lundin recounts the struggles we all face at times trying to make a story work.

Dickens’ A Christmas Carol -- Dale Andrews' holiday essay on one of the favorite yuletide novels of all time.

My Thoughts on the Big Lie -- Santa Claus -- Louis Willis’ title says it all.

JANUARY 2012

Janus -- New Year reflections by Jan Grape.

Nothing But the Best -- Rob Lopresti offers his annual list of the previous year’s best mystery stories.

The Brazilian Connection -- The only SleuthSayers guest article by the great (and sadly, now late) Leighton Gage. A must read.

Profiled -- Deborah Elliott-Upton discusses profiling -- real life and fiction.

No, No, I Really Am . . . -- Undercover stories from R.T. Lawton, who has been there and done that.

Tricky Diction -- John Floyd’s hilarious piece on “saying it right.”

Red Rum -- Fran Rizer gives us a two-for. First, her reflections on real-life South Carolina murderers, and second Evelyn Baker’s chilling account of “The Good Twins.”

Character Flaws -- Jan Grape talks about how to make fictional character real.

FEBRUARY

RSI -- A SleuthSayers classic by Rob Lopresti. No spoiler here -- just go and read it!

Computers? They're not my Type -- Guest columnist Herschel Corzine grouses humorously about being dragged, kicking and screaming, into the future. Err, present!

Mind Control -- David Dean looks at mind control and, in the process, re-examines Patty Hearst and the Symbionese Liberation army.

Waging Love in Ink -- Dixon Hill’s salute to Valentine’s Day.

Before Stalking had a Name -- Liz Zelvin's personal (and chilling) account of stalking.

Beginnings -- Janice Law talks about how to get the first paragraph right.

No Name Blog -- Jan Rizer on the curse of all mystery writers -- rejection.

Daturas -- An article discussing a beautiful flower that is also a dangerous narcotic and poison. The mystery to the author, Dale Andrews, is how this article, which garnered only a few comments, became the most widely read in the history of SleuthSayers

MARCH

Lawyers and Writers, Oh My! -- Deborah Elliott-Upton’s send-up of lawyers generally and lawyer authors particularly.

The Sixth Sense -- R. T. Lawton discusses where those premonitions may be coming from.

A Familiar Face -- John Floyd provides a road-map for spotting all those cameos by Alfred Hitchcock.

APRIL

Florida’s Right to Kill Law -- A serious piece by Leigh Lundin, and one of a series, exploring real life crime in Florida. This provides early insight into the Travon Martin case and Florida’s “Stand your Ground” statute.

Young at Heart (and Death) -- Fran Rizer looks at fairy tales over the years.

Evil Under the Sun (Part One and Two) -- David Dean’s riveting account of a murder and subsequent investigation in the Bahamas. In two parts.

Easter Eggs -- the Sequel -- Dale Andrews explores the recurring, obscure and perplexing references to Easter that occur throughout the works of Ellery Queen.

Close, but no Springroll -- Neil Schofield's personal account of how things sometimes get lost in translation when mysteries cross the Pacific.

Outrageous Older Woman: Getting the Music Out There -- Liz Zelvin shows that she sports more than just a literary hat.

Rewrite, Rewrite, Rewrite -- Jan Grape warns us to do exactly what the title orders.

Paraprosdokia -- Dale Andrews' humorous collection of those sayings that, like many mysteries, sport a surprise ending.

The Court Reporter’s Tale -- Forget about television depictions. Eve Fisher shows us the criminal justice system from the inside.

No, Thank You -- R.T. Lawton discusses drug use among police officers and why it is a rare occurrence.

Deja Vu All Over Again -- John Floyd’s discussion of commonplace redundancies in the English language.

My Two Cents Worth -- Louis Wills discusses the ever-present debate concerning the literary worth of genre versus literary fiction.

MAY

Tough Broads -- Deborah Elliott-Upton’s advice on writing strong female characters.

Cowboy Days -- R.T. Lawton re-visits the rodeo experiences of his childhood.

Dream On -- John Floyd addresses the glory and the tedium of book signing events.

Crime and PUNishment -- Leigh Lundin continues a spate of literary humor that infected us all that spring.

Worst of the First -- The groans continue with Fran Rizer’s collection of the worst introductory passages ever written.

A Word about Crime -- Turning the tables, Rob Lopresti offers a collection of some of his favorite quotes from crime fiction.

Silence is Golden -- Dixon Hill addresses various audible intrusions that are just going to happen. So don’t pretend that they won’t in your stories.

Hell’s Bellows -- Dale Andrews proves that lawyers have long memories when he finally serves up a response to Deborah’s March column on lawyer authors.

It’s Alive! -- David Dean recounts the travails, obstacles and joys encountered in writing his first novel, The Thirteenth Child.

Notes from the Penitentiary -- Eve Fisher gives us a look at what it is like, everyday, inside.

Trifling through “Trifles” -- Deborah Elliott-Upton addresses the early lack of meaningful women characters in detective stories, and the fight to overcome the "trifles" characterization.

JUNE

How do you Write a Crime Novel? -- Jan Grape collects the best advice from some who have done it.

The Asparagus Bed -- Nearly a full year of essays and -- finally -- a real story! A gem by Eve Fisher.

It’s a Long Story -- John Floyd discusses the novella -- one of the most difficult types of story to market.

Professional Tips -- Ray Bradbury -- Leigh Lundin offers a collection of story telling tips from the master.

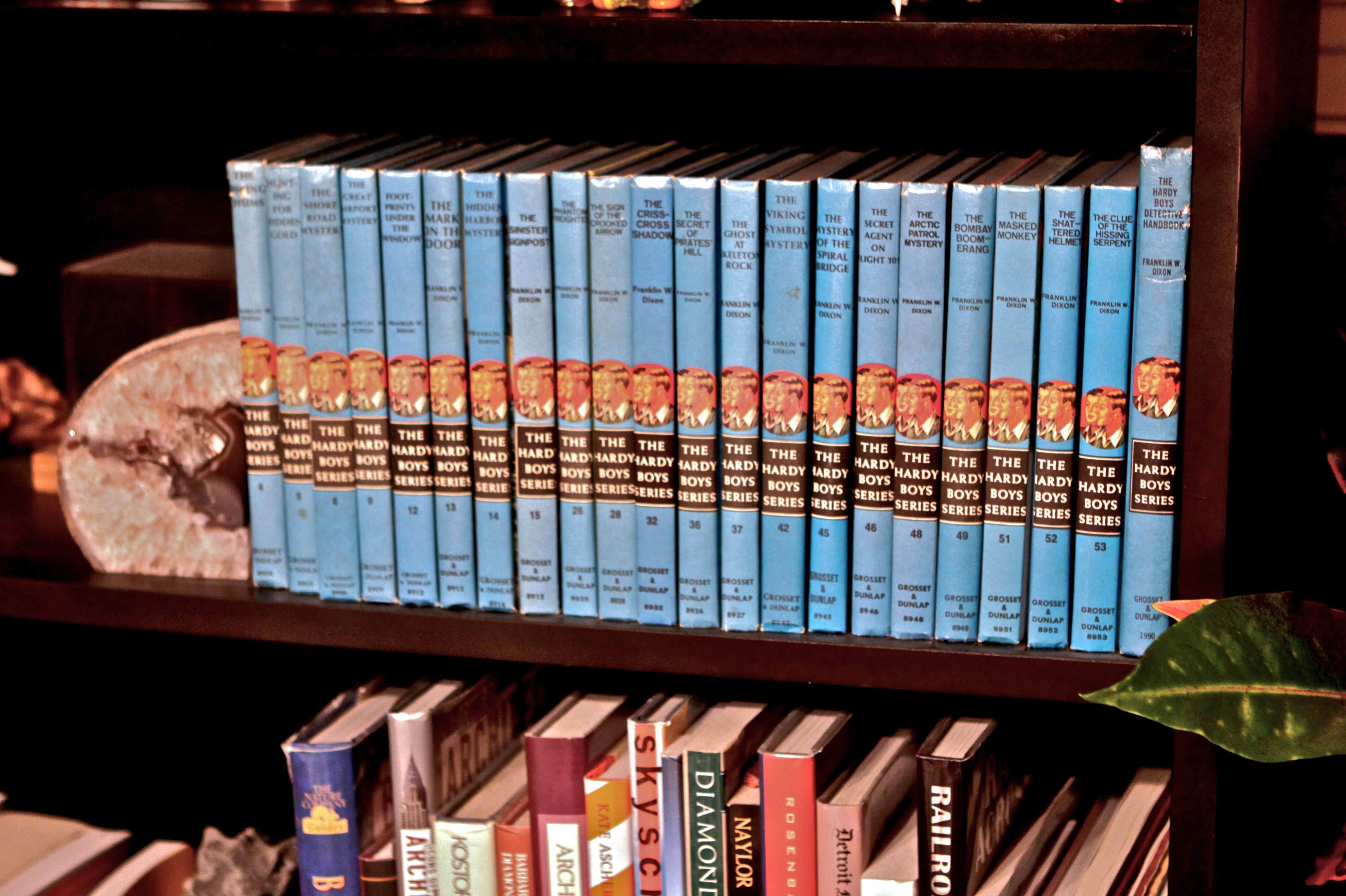

Do Books Change over Time or Is it Me? -- Liz Zelvin explores a recurring theme on SleuthSayers -- returning to the books of our youth.

ABC -- Idle thoughts on Auden, Bradbury and Christie by Neil Schofield.

Summertime and the Heat is Killing Me -- That’s what heat will do to you, as Deborah Elliott-Upton explains.

Guys Read -- Among kids it’s easier to find girl readers. Dixon Hill discusses motivating boys to become lifelong readers and a project aimed at accomplishing that.

The Unmaking of Books -- As always, an entertaining glimpse inside the thought process of Rob Lopresti.

Selling Short -- Looking for a market for your short story? An invaluable guide by John Lloyd, who has sold hundreds.

AKA -- Fran Rizer discusses early women writers who decided to publish under male pseudonyms.

JULY

The Writing Life -- Janice Law gives us a two-bladed essay on Latin words that stick to the English language like glue and trying to fathom why some stories work for the writer but not for the reader. Or at least not for the reader writing those rejection letters!

E-Volution -- Dale Andrews’ essay on Michael S. Hart, the founder of Project Guttenberg.

Forty Whacks -- Yep, David Dean tells us all about Lizzie Borden.

Summer Love -- Rob Lopresti begins writing a novel and falls in love.

Brain Exercises -- Jan Grape explains how writers can hone their craft by paying attention to what works of other writers.

AUGUST

Two Golden Threads -- Rob Lopresti’s loving memorial to John Mortimer.

Sovereign Citizens -- Strange characters? Sometimes they are all around us. Ask Eve Fischer.

Me and the Mini Mystery -- R.T. Lawton offers tips on how to tackle the mini market..

John Buchan: The Power House -- David Edgerton Gates’ first SleuthSayers article tells us all about the author of The Thirty Nine Steps and one of his best books -- The Power House.

A Woman’s World Survivors’ Guide -- John Floyd’s hornbook on what Woman’s World looks for in a mini-mystery.

She Said What? -- Fran Rizer’s tribute to Helen Gurley Brown.

The Name is Familiar -- Rob Lopresti looks at eponyms -- people whose names became words.

What Do You Do? -- Jan Grape talks about tackling writers’ block.

Ellery Queen’s Backstory -- Well, it’s complicated, as Dale Andrews explains.

My Favorite Characters -- Eve Fisher discusses how she finds inspiration for characters all around her.

Copyedited by Tekno Books -- R.T. Lawton explains how it wasn't all fun after his short story was accepted for inclusion in the latest MWA anthology.

SEPTEMBER

The Fires of London -- Janice Law discusses her newest novel on the day before publication.

A “Feyn” Idea -- Dixon Hill’s intriguing article on famed physicist Richard Feynman.

Locke and Leather -- Leigh Lundin explores some of the darker sides of self-publishing.

The Washed and the Unwashed -- John Floyd takes another look at differences between literature and genre fiction.

And that is it for year one! Next week Terry will post his take on the highlights of SleuthSayers -- Year Two!