Okay, so it's the day after Valentine's Day, which means that my turn for an article comes up one day late to land directly on the 14th, but I hope you'll allow me a little leeway here. See, Valentine's Day is my wedding anniversary, so just pretend that everything is correctly aligned. Naturally, I'm supposed to be sentimental during this holiday of the year and thus, shall we say, exposing my softer side to my significant other. One further fact to know, if all goes according to plan, she and I should be lounging in Maui for the umpteenth time even as you read this. (I strongly suspect that Kiti slipped that little clause into the fine print of our marriage contract when I wasn't looking.)

Anyway, Valentine's Day speaks of lovers, romance, flowers, chocolates, roughly anything that melts the female heart and makes it go all gooey. At this point, you, the reader, will have to reflect back into your own Valentine's Days of the past and dwell pleasurably for a couple of moments on whatever worked for you.

In my case, my wife has a little red book stashed away in the lingerie drawer of her dresser. This particular hard-bound book is filled with hand-written poems composed by yours truly whilst gripped in the all encompassing embrace of infatuation. I'm sure most of you have been in some form of that condition at one stage or another of your life. To that end, I wrote all these poems in order to win the hand and heart of my lady love, and in the process filled up every page in that little red book. And no, you can't read it.

Most of the poems are very personal and/or have meaning only to the two of us. Realize that these scribblings aren't exactly sonnets by Shakespeare. Furthermore, need I remind you that when I returned to college shortly after my twelve month tour of Southeast Asia, I took my war poems into the WSU English Department seeking further guidance along these lines and was promptly not encouraged to continue any efforts in the field of poetry. But due to persistence (some would politely suggest hard-headedness) it turns out that the heart likes what the heart likes.

As a sample of my beginning strategy in this win-the-heart endeavor, here's part of an early poem during the courtship:

Please forgive my muddled mind,

it's seldom on the path.

It's not so good in English

and even worse in math.

But as I recall the contract

or the game as it is played,

one poem for one kiss

was the bargain that we made.

* * (okay, skip to closing) * *

I have no fear about the debt

for as I can plainly see,

you are a lady on your honor

and would not a debtor be.

Oh yeah, working on getting that kiss. Okay, so you had to be there. Shelley or Byron, it's not. Probably not even as good as the first recorded Valentine poem written by Chaucer in 1382 for King Richard the Second to give to his intended bride, and that one was composed in the language of Middle English, but mine are at least a step up from the "Roses are red, Violets are blue..." category. My main point being, hey, give the love of your life some personal hand-written poetry and watch their eyes light up. Go ahead, it's not too late even if Valentine's Day was actually yesterday. It doesn't need to be a professional job, it just needs to be from you, from your heart.

Yep, you can bet I got kissed with them poems. A lot. A whole book full, you might say.

15 February 2013

A Day for the Heart

by R.T. Lawton

14 February 2013

References, Anyone?

by Eve Fisher

I know that you can get everything on the internet any more, but I still think it's handy to have a shelf of reference works. I still have a big fat dictionary, a Roget's thesaurus (the on-line ones are awful), Bartlett's Quotations (the on-line ones are almost all modern), a Dictionary of Science, of Language, of Foreign Terms, of Japan, of various other things, as well as the following foreign languages: Spanish, French, German, Gaelic, Greek (Demotic and ancient), Latin, Chinese, Japanese, and (my personal favorite) Colloquial Persian.

There are history textbooks, of which I have shelves, and also certain history books that I consider mandatory for giving you the real flavor of a time and place (what I call time-travel for pedestrians").

Liza Picard has written a whole series (and I have them all) about London: "Elizabeth's London", "Restoration London", "Dr. Johnson's London", "Victorian London."

Liza Picard has written a whole series (and I have them all) about London: "Elizabeth's London", "Restoration London", "Dr. Johnson's London", "Victorian London."

Judith Flanders has written many works on Victorian England, of which I have: "Inside the Victorian home : a portrait of domestic life in Victorian England", and "Consuming passions : leisure and pleasure in Victorian Britain." What she doesn't tell about Victorian daily life isn't worth telling. Her most recent work - just out, which I have got on order even as I write - is "The invention of murder : how the Victorians revelled in death and detection and created modern crime." Woo-hoo!

Speaking of every day life, there's the "Everyday Life in America Series", which includes "Every day Life in Early America," "The Reshaping of Every Day Life 1790-1840", "Victorian America", "The Uncertainty of Everyday Life 1915-1945", etc. I have them all.

As some of you may remember, I used to teach Asian history at SDSU. I have TONS of books on Japanese and Chinese history, and making a list of them... Well, what do you want to know? Let's just hit some highlights about Japan for today:

The first thing to read is Ivan Morris' "The World of the Shining Prince", about Heian Japan, specifically the 11th century Heian Japan of the Lady Murasaki Shikibu, author of "The Tale of Genji" (Note about Genji - there are 3 good English translations, and I have them all. I LOVE THIS BOOK. Feel free to e-mail me any time to discuss it; it's one of my obsessions.)

first thing to read is Ivan Morris' "The World of the Shining Prince", about Heian Japan, specifically the 11th century Heian Japan of the Lady Murasaki Shikibu, author of "The Tale of Genji" (Note about Genji - there are 3 good English translations, and I have them all. I LOVE THIS BOOK. Feel free to e-mail me any time to discuss it; it's one of my obsessions.)

"Legends of the Samurai" by Hiroaki Sato - from the 4th century to the 19th, these are the stories the samurai told about themselves, building the mythos of the samurai - slowly - over time.

"Japan Rising: The Iwakura Embassy to the USA and Europe 1871-1873" compiled by Kume Kunitake. See the USA and Europe through the eyes of Japanese who had never been West before - and weren't particularly impressed. (And who foresee the need for Japan to oversee the Pacific Ocean.)

"Memories of Silk and Straw: a Self-Portrait of Small Town Japan" by Dr. Junichi Saga - Japan before WW2.

John Gunther (1901-1970) wrote a series of "Inside" books in the 1930s and 40s which are snapshots of Europe and Asia. I am the proud possessor of two: "Inside Asia - 1939"; "Inside Europe - 1938". I consider these priceless because they were written, fairly objectively, before World War II: and not all the portraits are recognizable by today's standards, especially those of Hitler and his gang. This is BEFORE the world was willing to accept that they were crazy. Did you know that Mussolini was considered an intellectual? Did you know that Putzi Hanfstaengl played piano to put Hitler to sleep every night?

Don't forget diaries. St. Simon's diary of the Versailles under Louis XIV and Louis XV; the diary of Colonial midwife, Martha Ballard; Lady Murasaki and a host of other upscale women of Heian Japan all kept diaries, and let us never forget Sei Shonagon's "Pillow Book"; Parson Woodforde's diary of 18th century rural Britain; Samuel Pepys, of course; and any others that you can get your hands on for the period/time/place you're interested in. WARNING: what I've found is that reading a diary of a period/time/place I'm not particularly interested in can generate a whole new passion...

And then there are maps. Besides collecting all this other stuff (and I didn't even get to the Chinese daily life histories, etc.) I have atlases galore, including a couple that are very old. (One came with a church insert that explained the League of Nations, which in itself was worth the price of the book!) I have regular atlases, an Atlas of World History, of the British Empire, of the Middle Ages, of War, of Ancient Empires, etc. And a bunch of plain old road atlases. If nothing else, when I'm really stuck, I can pull them out and plan my next road trip...

I'm not sure where it is, but I'm interested in going there...

There are history textbooks, of which I have shelves, and also certain history books that I consider mandatory for giving you the real flavor of a time and place (what I call time-travel for pedestrians").

Liza Picard has written a whole series (and I have them all) about London: "Elizabeth's London", "Restoration London", "Dr. Johnson's London", "Victorian London."

Liza Picard has written a whole series (and I have them all) about London: "Elizabeth's London", "Restoration London", "Dr. Johnson's London", "Victorian London." Judith Flanders has written many works on Victorian England, of which I have: "Inside the Victorian home : a portrait of domestic life in Victorian England", and "Consuming passions : leisure and pleasure in Victorian Britain." What she doesn't tell about Victorian daily life isn't worth telling. Her most recent work - just out, which I have got on order even as I write - is "The invention of murder : how the Victorians revelled in death and detection and created modern crime." Woo-hoo!

Speaking of every day life, there's the "Everyday Life in America Series", which includes "Every day Life in Early America," "The Reshaping of Every Day Life 1790-1840", "Victorian America", "The Uncertainty of Everyday Life 1915-1945", etc. I have them all.

As some of you may remember, I used to teach Asian history at SDSU. I have TONS of books on Japanese and Chinese history, and making a list of them... Well, what do you want to know? Let's just hit some highlights about Japan for today:

The

first thing to read is Ivan Morris' "The World of the Shining Prince", about Heian Japan, specifically the 11th century Heian Japan of the Lady Murasaki Shikibu, author of "The Tale of Genji" (Note about Genji - there are 3 good English translations, and I have them all. I LOVE THIS BOOK. Feel free to e-mail me any time to discuss it; it's one of my obsessions.)

first thing to read is Ivan Morris' "The World of the Shining Prince", about Heian Japan, specifically the 11th century Heian Japan of the Lady Murasaki Shikibu, author of "The Tale of Genji" (Note about Genji - there are 3 good English translations, and I have them all. I LOVE THIS BOOK. Feel free to e-mail me any time to discuss it; it's one of my obsessions.)"Legends of the Samurai" by Hiroaki Sato - from the 4th century to the 19th, these are the stories the samurai told about themselves, building the mythos of the samurai - slowly - over time.

"Japan Rising: The Iwakura Embassy to the USA and Europe 1871-1873" compiled by Kume Kunitake. See the USA and Europe through the eyes of Japanese who had never been West before - and weren't particularly impressed. (And who foresee the need for Japan to oversee the Pacific Ocean.)

"Memories of Silk and Straw: a Self-Portrait of Small Town Japan" by Dr. Junichi Saga - Japan before WW2.

John Gunther (1901-1970) wrote a series of "Inside" books in the 1930s and 40s which are snapshots of Europe and Asia. I am the proud possessor of two: "Inside Asia - 1939"; "Inside Europe - 1938". I consider these priceless because they were written, fairly objectively, before World War II: and not all the portraits are recognizable by today's standards, especially those of Hitler and his gang. This is BEFORE the world was willing to accept that they were crazy. Did you know that Mussolini was considered an intellectual? Did you know that Putzi Hanfstaengl played piano to put Hitler to sleep every night?

Don't forget diaries. St. Simon's diary of the Versailles under Louis XIV and Louis XV; the diary of Colonial midwife, Martha Ballard; Lady Murasaki and a host of other upscale women of Heian Japan all kept diaries, and let us never forget Sei Shonagon's "Pillow Book"; Parson Woodforde's diary of 18th century rural Britain; Samuel Pepys, of course; and any others that you can get your hands on for the period/time/place you're interested in. WARNING: what I've found is that reading a diary of a period/time/place I'm not particularly interested in can generate a whole new passion...

And then there are maps. Besides collecting all this other stuff (and I didn't even get to the Chinese daily life histories, etc.) I have atlases galore, including a couple that are very old. (One came with a church insert that explained the League of Nations, which in itself was worth the price of the book!) I have regular atlases, an Atlas of World History, of the British Empire, of the Middle Ages, of War, of Ancient Empires, etc. And a bunch of plain old road atlases. If nothing else, when I'm really stuck, I can pull them out and plan my next road trip...

I'm not sure where it is, but I'm interested in going there...

13 February 2013

Herbert O. Yardley: The American Black Chamber

by David Edgerley Gates

Herbert Yardley was never a household name, but among his peers, he was almost godlike. He was, in effect, the father of American codebreaking. (He was also, it happens, one hell of a poker player. You do the math.)

Yardley started out as a code clerk at the State Dept., in 1912. His first significant coup de theatre came when he intercepted a coded message to President Wilson from Wilson's close personal aide, Colonel House. This was before America entered the European warm and House had been sent to meet the Kaiser: here was his confidential report. On a dare, we might say, Yardley broke the encrypted traffic in two hours, and realizing just how vulnerable American diplomatic cipher systems were, he took the results to his boss. The fuse was lit. In 1917, with America now in the war, Yardley got a commission and went to work for the War Dept., heading up MI-8, codes and ciphers, and eventually turned it into the first real U.S. cryptographic intelligence operation. 1918 found him at Versailles for the peace conference, and his shop encoded American traffic, while secretly decoding those of their Allies. Of course, the French and the British were doing the same thing, and Yardley by this time was no innocent in duplicity.

The war over, Yardley headed home, assuming he was out of a job. But meanwhile, Military Intelligence and the State Dept. had decided to pool their resources, and establish a full-time clandestine eavesdropping organization, with a black budget, hidden from the Comptroller General. Yardley was given the mandate. They were up and running by May of 1919, and in December, Yardley hit the jackpot, when he cracked the Japanese encipherment protocols, and opened up their coded military and diplomatic cables. This was a big deal, and it gave the American negotiators at the 1921 disarmament conference an enormous advantage. The object of the conference, between the five major naval powers, the U.S., Britain, France, Italy, and Japan, was to stabilize the ratio of seapower tonnage. Basically, each navy would agree to a limit on warships, relative to the navies of the other countries. Japan was aggressively pursuing a higher limit for the Imperial Navy, and even at this stage, U.S. and British military strategists were disturbed by Japanese ambitions in the Pacific. But what Japan's admirals said publicly at the negotiating table was undercut by their secret instructions from Tokyo, which conceded political realities. Yardley, knowing his way around a game of stud poker, compared this to knowing your opponent's hole card, and in the end, the Japanese caved. It was high-water mark for American intelligence capacities, and for Yardley, personally, who never minded the attention.

There were, however, clouds on the horizon. Wartime cable censorship was over. Communications were supposed to be private. Yardley, or high-ranking military surrogates, approached the major telegraph companies, and strong-armed them into continuing to supply their cable traffic. This was, of course, completely illegal, unless you got a search warrant, and Yardley couldn't blow his cover by doing any such thing. His operation flew under the radar. He turned to the Signal Corps, but State spiked the idea of setting up Army listening posts. Yardley had started his operation with fifty people, and expanded with the heavy demand. By 1929, with the Depression, his staff was down to seven, and badly demoralized, their astonishing successes forgotten. Times had changed. Hoover was president, now. Yardley gambled it all on one last throw of the dice. He went to the Secretary of War, the newly-appointed Henry Stimson, and put his chips on the table. Here, for example, are the recent Japanese decrypts, he told Stimson. And perhaps as a joke, or just to show off, Yardley said he could read the Vatican's private communications. Exaggeration for effect? We don't know. The joke apparently fell flat. Yardley had bet into a stronger hand.

We imagine a moment of stony silence.

Stimson then comes up with a next to legendary line, in the clandestine world. He looks at Yardley, and says---wait for it---"Gentlemen don't read other gentlemen's mail." And with this, Yardley is put out to pasture, his operation dismantled, and their efforts ignored, if not disgraced.

Yardley, in his uppers, writes a book, THE AMERICAN BLACK CHAMBER. Published in 1931, it's a sensation. Washington hunkers down. William Friedman, another big-time cryptologist, now chief of Codes and Ciphers, is in a fury, because Yardley's book gives up sources and methods. He has a point, since the Japanese immediately change their encipherment programs. Friedman won't break the Purple Code until late in WWII. But the government can't embargo Yardley's book. He's not in violation of any existing security laws. And it's something Yardley's thought about. He himself wonders if he's letting the genie out of the bottle. But, he decides, men like Stimson have their heads in the sand. He goes ahead with publication, in spite of his own doubts, and the ship pushes slowly back against the iceberg. Inertia bows to necessity.

Yardley works for the Canadian government, and later the Nationalist Chinese. He writes another book. Suppressed, for whatever reason, by the U.S. government, but afterwards declassified. Not exactly a victim, like Alan Turing, but sort of forgotten. Yardley was a tireless self-promoter, a guy who never shunned the limelight, and maybe took credit for other people's labors, but for all that, he's still the man behind the curtain.

NSA is the largest of the American intelligence agencies, dwarfing CIA. National Reconnaissance had the bigger budget, because they put satellites in orbit, but Ft. Meade has the personnel, and the brute mainframes, and the black budget. They can suck the air out of a room. This is perhaps Herbert Yardley's legacy. Not that he thought of it that way. I doubt if he imagined a world where they can read all our mail.

He would have preferred to read all the cards.

[Many of the specifics here are taken from David Kahn's book THE CODEBREAKERS, and James Bamford's THE PUZZLE PALACE, two excellent resources.]

Herbert Yardley was never a household name, but among his peers, he was almost godlike. He was, in effect, the father of American codebreaking. (He was also, it happens, one hell of a poker player. You do the math.)

Yardley started out as a code clerk at the State Dept., in 1912. His first significant coup de theatre came when he intercepted a coded message to President Wilson from Wilson's close personal aide, Colonel House. This was before America entered the European warm and House had been sent to meet the Kaiser: here was his confidential report. On a dare, we might say, Yardley broke the encrypted traffic in two hours, and realizing just how vulnerable American diplomatic cipher systems were, he took the results to his boss. The fuse was lit. In 1917, with America now in the war, Yardley got a commission and went to work for the War Dept., heading up MI-8, codes and ciphers, and eventually turned it into the first real U.S. cryptographic intelligence operation. 1918 found him at Versailles for the peace conference, and his shop encoded American traffic, while secretly decoding those of their Allies. Of course, the French and the British were doing the same thing, and Yardley by this time was no innocent in duplicity.

The war over, Yardley headed home, assuming he was out of a job. But meanwhile, Military Intelligence and the State Dept. had decided to pool their resources, and establish a full-time clandestine eavesdropping organization, with a black budget, hidden from the Comptroller General. Yardley was given the mandate. They were up and running by May of 1919, and in December, Yardley hit the jackpot, when he cracked the Japanese encipherment protocols, and opened up their coded military and diplomatic cables. This was a big deal, and it gave the American negotiators at the 1921 disarmament conference an enormous advantage. The object of the conference, between the five major naval powers, the U.S., Britain, France, Italy, and Japan, was to stabilize the ratio of seapower tonnage. Basically, each navy would agree to a limit on warships, relative to the navies of the other countries. Japan was aggressively pursuing a higher limit for the Imperial Navy, and even at this stage, U.S. and British military strategists were disturbed by Japanese ambitions in the Pacific. But what Japan's admirals said publicly at the negotiating table was undercut by their secret instructions from Tokyo, which conceded political realities. Yardley, knowing his way around a game of stud poker, compared this to knowing your opponent's hole card, and in the end, the Japanese caved. It was high-water mark for American intelligence capacities, and for Yardley, personally, who never minded the attention.

There were, however, clouds on the horizon. Wartime cable censorship was over. Communications were supposed to be private. Yardley, or high-ranking military surrogates, approached the major telegraph companies, and strong-armed them into continuing to supply their cable traffic. This was, of course, completely illegal, unless you got a search warrant, and Yardley couldn't blow his cover by doing any such thing. His operation flew under the radar. He turned to the Signal Corps, but State spiked the idea of setting up Army listening posts. Yardley had started his operation with fifty people, and expanded with the heavy demand. By 1929, with the Depression, his staff was down to seven, and badly demoralized, their astonishing successes forgotten. Times had changed. Hoover was president, now. Yardley gambled it all on one last throw of the dice. He went to the Secretary of War, the newly-appointed Henry Stimson, and put his chips on the table. Here, for example, are the recent Japanese decrypts, he told Stimson. And perhaps as a joke, or just to show off, Yardley said he could read the Vatican's private communications. Exaggeration for effect? We don't know. The joke apparently fell flat. Yardley had bet into a stronger hand.

We imagine a moment of stony silence.

Stimson then comes up with a next to legendary line, in the clandestine world. He looks at Yardley, and says---wait for it---"Gentlemen don't read other gentlemen's mail." And with this, Yardley is put out to pasture, his operation dismantled, and their efforts ignored, if not disgraced.

Yardley, in his uppers, writes a book, THE AMERICAN BLACK CHAMBER. Published in 1931, it's a sensation. Washington hunkers down. William Friedman, another big-time cryptologist, now chief of Codes and Ciphers, is in a fury, because Yardley's book gives up sources and methods. He has a point, since the Japanese immediately change their encipherment programs. Friedman won't break the Purple Code until late in WWII. But the government can't embargo Yardley's book. He's not in violation of any existing security laws. And it's something Yardley's thought about. He himself wonders if he's letting the genie out of the bottle. But, he decides, men like Stimson have their heads in the sand. He goes ahead with publication, in spite of his own doubts, and the ship pushes slowly back against the iceberg. Inertia bows to necessity.

Yardley works for the Canadian government, and later the Nationalist Chinese. He writes another book. Suppressed, for whatever reason, by the U.S. government, but afterwards declassified. Not exactly a victim, like Alan Turing, but sort of forgotten. Yardley was a tireless self-promoter, a guy who never shunned the limelight, and maybe took credit for other people's labors, but for all that, he's still the man behind the curtain.

NSA is the largest of the American intelligence agencies, dwarfing CIA. National Reconnaissance had the bigger budget, because they put satellites in orbit, but Ft. Meade has the personnel, and the brute mainframes, and the black budget. They can suck the air out of a room. This is perhaps Herbert Yardley's legacy. Not that he thought of it that way. I doubt if he imagined a world where they can read all our mail.

He would have preferred to read all the cards.

[Many of the specifics here are taken from David Kahn's book THE CODEBREAKERS, and James Bamford's THE PUZZLE PALACE, two excellent resources.]

12 February 2013

Gone South (with Travis McGee)

by Dale Andrews

|

| Sunset, Gulf Shores Alabama |

Just like last year, this month finds my wife and me transplanted from Washington, D.C. to the sunny south. February, despite those limited number of days, is clearly the longest month in the year when spent in North Eastern climes, a fact that Boston has recently seen underscored.

It always seemed to me that whoever made February the month with the fewest days was on to something. Better still, it should have had 21 days – allow it three weeks and no more. Then slip that extra week into June where it would be appreciated instead of cursed.

Anyway, when Pat and I retired back in 2009 we vowed to never spend February in the District of Columbia. That is why on this “Shrove Tuesday” (or “Fat Tuesday,” as it is more popularly referred to) we find ourselves ensconced in a rented condo unit on the beach in Gulf Shores, Alabama.

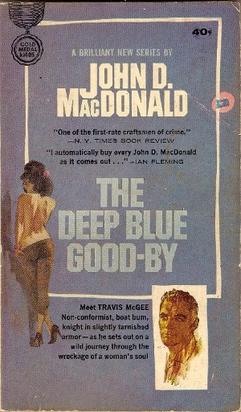

| John D. MacDonald |

Two weeks ago in my article on Francis Nevin’s new Ellery Queen work The Art of Detection I quoted Mike Nevin’s observation that as a general matter “when the author dies, the work dies.” In a similar vein, Jonathan Yardley’s article in the Washington Post noted that while

[t]he McGee novels have remained in print in mass-market editions . . . most of the other books by this prodigiously proficient writer long ago vanished. . . . To be sure, some characters in suspense fiction have long outlived their creators – think Lord Peter Wimsey, Sam Spade, Miss Marple and Philip Marlowe – but mostly they just fade away, a fate that surely seemed in store for Travis McGee.What a shame that would have been. Kurt Vonnegut once predicted that “[t]o diggers a thousand years from now . . . the works of John D. MacDonald would be a treasure on the order of the tomb of Tutankhamen.”

And what has been the catalyst for this MacDonald (and McGee) revival, saving us (at least in the near term) from such excavation? Well, according to Random House it is (counter-intuitively) the blooming e-book market. The anticipated new appetite for e-book versions of the McDonald library is projected to be strong enough to propel new issues of e-books and paper versions as well. So this rising tide appears to be enough to lift all boats.

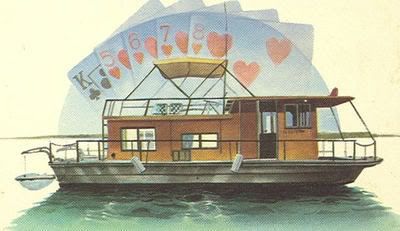

And that happily includes the Busted Flush. For any of you unfamiliar with the series, the Busted Flush was Travis McGee’s 52 foot houseboat, on which he resided at Slip F-18 in the Bahia Mar Marina in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. The ship’s name is derived from the poker hand that allowed McGee to win the Busted Flush from its previous unnamed owner.

And that happily includes the Busted Flush. For any of you unfamiliar with the series, the Busted Flush was Travis McGee’s 52 foot houseboat, on which he resided at Slip F-18 in the Bahia Mar Marina in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. The ship’s name is derived from the poker hand that allowed McGee to win the Busted Flush from its previous unnamed owner.And Travis McGee? Well, McGee advertises himself as a “salvage consultant.” He recovers otherwise hopelessly lost property for a fee of one-half the value. As McGee explains it in The Deep Blue Good-by, the first volume in the series, “I like to work on pretty good sized [projects]. Expenses are heavy. And then I can take another piece of my retirement. Instead of retiring at sixty, I’m taking it in chunks as I go along.” As McGee also explains, there is always a need for the services he offers. We live, McGee notes, in “a complex culture . . . . The more intricate our society gets, the more semi-legal ways there are to steal.” His simple role is putting things back to right.

What made these novels such great reads? Well, principally the taut writing and prolific imagination of John D. MacDonald. The books follow a formula, but a pretty wild one. All the reader really knows is that the hero, our friend Travis, will prevail and will still be around by the last page. This is also true of his sidekick, Meyer, an economist who lives (first) on his neighboring ship the John Maynard Keynes and later on the successor vessel, the Thorstein Veblen. But aside from those two compadres, all bets are off, and virtually every other character struts and frets the pages in danger of extinction.

The success of the series also rests on the likeable shoulders of the characters MacDonald created. Some writers leave their central character to the imagination of the readers (Ellery Queen, for example, unraveled mysteries for decades virtually un-described; Bill Pronzini’s hero doesn’t even have a name.) By contrast, we know a huge amount about Travis McGee, including what he looks like and how he thinks..

McGee, we are told, is a shambling brown beach bum with a 33-inch waist, who wears a size 46 long jacket, and a shirt with a 17½" neck and 34" arms. He is likely to rail against anyone abusing the fragile ecosystem of his beloved Florida, and he wears his views on his shirt sleeve. MacDonald, writing for the first-person narrator McGee, describes our hero’s views as follows in The Deep Blue Good-by:

I do not function too well on emotional motivations. I am wary of them. And I am wary of a lot of other things, such as plastic credit cards, payroll deductions, insurance programs, retirement benefits, savings accounts, Green Stamps, time clocks, newspapers, mortgages, sermons, miracle fabrics, deodorants, check lists, time payments, political parties, lending libraries, television, actresses, junior chambers of commerce, pageants, progress, and manifest destiny.

I am wary of the whole dreary deadening structured mess we have built into such a glittering top-heavy structure that there is nothing left to see but the glitter, and the brute routines of maintaining it.

. . . .

I am also wary of all earnestness.We get the picture.

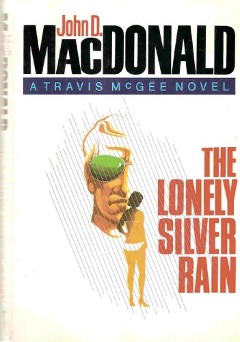

The Travis McGee series spanned 21 volumes, beginning in 1964 with The Deep Blue Good-by and ending in 1985 with The Lonely Silver Rain. Each volume sported its own color.

The Travis McGee series spanned 21 volumes, beginning in 1964 with The Deep Blue Good-by and ending in 1985 with The Lonely Silver Rain. Each volume sported its own color.Rumors persisted for years that a final volume, usually titled A Black Border for McGee, had been completed and that the book would kill off McGee. MacDonald himself alluded to the volume in several interviews, saying that it would be published following his own death. Almost certainly no such volume was ever written, and McDonald stated in later years that he would never kill off McGee since this would create a brooding ending hanging over the heads of new readers discovering the series. We do know, according to letters written by McDonald to Mickey Spillane and to Stephen King that at the time of MacDonald's death following heart surgery in 1986 he had completed four chapters of what was to have been the 22nd Travis McGee adventure. MacDonald also said that the story would be in two parts, spanning twenty years, and that it would end with with McGee still very much alive but slipping the lines off the pier and moving the Busted Flush to new moorings. The completed chapters alluded to by MacDonald have never been found.

Since MacDonald’s death in 1986 various offers to otherwise end the series, including one from Stephen King, have been rejected by MacDonald’s heirs. Just last year MacDonald’s son Maynard explained this decision to leave the series at the 21 volumes written by MacDonald:

[T]he offers to extend my father's work have run from a tacky, blatant, commercial knock-off to a respectful, professional postscript to his work by a true friend [i.e., King]. And between those extremes there have been many well-crafted manuscripts that were done with warm regard and sincere admiration for my old man.

As these offers and manuscripts continued, and the enthusiasm from Random House snowballed, I was forced to finally define and face my own personal resistance to the idea of a sequel.

Given that I am not immune to the money, why refuse?

It is because I have never seen a really good imitation, be it art, literature, or music, that carries that poignant echo of the original artist- as a man. Even if the work itself is excellent, there is an inevitable flatness on that most intimate level, the level where the artist reveals himself.

To me, a work of art is a souvenir of the artist. It is a reflection of his inner and outer experience. It represents who he is and where he has got to at that moment of his life. In this sense, the creative process defies copying. I enjoy my father's work immensely. Part of him is still there, present on each page. Trying to echo that by imitating it is like trying to paint like Van Gogh by cutting off an ear. It also strikes me as a question of fairness. The dead cannot answer back and I feel it is presumptuous and disrespectful to play with their work.As someone whose published mystery output consists solely of pastiches I have some perhaps understandable quibbles with Maynard’s view. But hey, it’s not my decision. So while we can expect no new McGees, we, in any event, will soon have new editions of all 21 existing McGee novels. As for what might have eventually happened to McGee, we are left to our own musings and those of others, including Carl Hiaasen:

Welcome back, McGee![P]ossibly the old houseboat is tied there still; McGee on deck, tending to fresh bruises, sipping his Boodles; watching the sun slide from the sky over Las Olas Boulevard. Anyway, that's what I want to believe. If he's gone, I prefer not to know.

Slip F-18, Bahia Mar, Ft. Lauderdale

Labels:

Dale C. Andrews,

John D. MacDonald,

Travis McGee

Location:

Gulf Shores, AL

11 February 2013

Travel In Style

by Jan Grape

On

most Tuesday and Wednesday evenings, I go to a nearby restaurant on Lake Marble

Falls to hear live music. (That's opposed to Dead Music, which I can’t seem to

ever understand because they're dead.) On Tuesday nights, it's Mike Blakely and

friends singing Tex-Americana. Mike not only writes and sings his original

songs, he is also an author of Western Historical fiction, and has won Spur

awards for a book and also for a song. He has a new book due out early summer,

written with Kenny Rogers about the music business (www.MikeBlakely.com).

On

most Tuesday and Wednesday evenings, I go to a nearby restaurant on Lake Marble

Falls to hear live music. (That's opposed to Dead Music, which I can’t seem to

ever understand because they're dead.) On Tuesday nights, it's Mike Blakely and

friends singing Tex-Americana. Mike not only writes and sings his original

songs, he is also an author of Western Historical fiction, and has won Spur

awards for a book and also for a song. He has a new book due out early summer,

written with Kenny Rogers about the music business (www.MikeBlakely.com).

On Wednesday nights,

it's john Arthur martinez (small caps on first & last name is correct). jAm

was on Nashville Star a few years ago and placed second behind winner Buddy

Jewel. Miranda Lambert came in third this same season. jAm sings a wonderful

mix of original Tex-Mex-Americana-Blues-country-funk ( www.johnArthurmartinez.net). Anyway, another fan of the

live music nights is Lenora, who happens to be a great travel agent. She set up

a Texas Music Cruise with Mike and jAm on Carnival Triumph, which left

Galveston last Saturday, February 2nd, and sailed to Progresso and Cozumel. The

cruise was for friends, family and fans of the musicians and I signed up last

summer to go.

I

drove with my cabinmate, Lottie Issacks, to Galveston last Friday as we planned

to spend the night in a hotel before boarding the ship on Saturday. We followed

the instructions to the hotel, which was located on Seawall Blvd, but I think

we got turned around when we stopped to refill the gas tank so we ended up lost

in the dark, driving around for about an hour. I mean, Seawall Blvd runs for

blocks and blocks along the beach but we just couldn’t seem to find it. Adding

to the confusion was the fact that many of the downtown streets were blocked

off because Galveston has a mini Mardi-Gras celebration and parade. Every time we

thought we could get somewhere we'd run into blocked dead-end. Finally, after

passing a parked taxi the second time, we pulled over and asked the driver for

directions. He hemmed and hawed and started to tell us three different times

then said, "Ladies I'll have to show you, I can't direct you from

here." He led us through several turns and eventually we wound up on the

back parking lot of the hotel. We got checked in and into our room a 9:15 pm.

We washed our faces, smoothed our hair and headed down stairs to the bar for a

much needed glass of wine. We asked our server about dinner and were told that

the dining room closed at 10:00. Since it was only 9:35 at this time, we did

get food. The next morning, we watched the Mardi-Gras parade from our eighth floor

balcony.

At

1:30 we hopped on the shuttle which took us to the Pier. Aboard the Carnival

Triumph, we had a wonderful cabin with a balcony so we were excited about being

able to watch for dolphins. This was Lottie's first cruise and at first she

couldn't believe all the food was included. There were two dinning rooms that

served three meals a day. If you didn't like what your ordered, say your

grilled fish wasn't all that good, all you had to do was send it back and order

Lasagna. Or, if your lobster tail and shrimp didn't fill you up, you could

order a prime rib. And the desserts were out of this world! My favorite was the

molten chocolate cake which is sort of a pudding cake with vanilla ice cream on

the side. Yummy. Besides the dinning room, the aft deck had deli food, burgers

& fries, hot dogs, soups, Chinese, Italian and pizza. If you were still

hungry, you could order room-service 24/7. No wonder people complain about

gaining weight on a cruise.

Our

musicians put on a two-hour show on Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday. They were

listed as private functions but we could invite anyone we wanted and if someone

wondered in, that was okay. The music was super and everyone had a great

time.

Our

first port of call was Progresso, Mexico. Lottie and I accompanied jAm and his

wife, Yvonna, and we walked to the oldest restaurant in town and had a

wonderful meal. We were sitting near an open window with a wonderful view of

the water and beach. After lunch, we walked over to the beach and while jAm got

a massage, we gals sat under a palapa and drank margaritas. A young man came

along, selling silver jewelry. We each bought something and within seconds, we

were set upon by people selling everything. They hit like vultures to fresh

roadkill! Our next port of call was Cozumel. Since I had been there twice

before, I stayed on board ship and read one of my books.

Later,

we all dressed up for formal dinner night and enjoyed a great meal. Then it was

on to the casino, where I managed to win enough to keep playing for a while.

That last night at sea, we experienced a rather wild storm that had the boat

rocking. It wasn't enough to make us sea-sick, but it was a little scary for

Lottie who said that if the first day had been like this she would have put on

a life-jacket and swam back to shore! Because of the storm, our captain put the

pedal to the metal and we docked two hours early at Galveston Pier Thursday

morning.

To me, this is a fantastic way to

travel. Even without our musicians, there's so much to do on a cruise ship:

bingo, trivia, Broadway shows, comedians, magic shows, shopping, card-playing,

swimming, sunning, fitness room…the list goes on and on. However, you are

constantly walking while on a ship. It seems like everything I wanted to do was

almost always at the other end of the boat from our cabin. Good thing, as it

keeps you from gaining too much from all that wonderful food!

Then, just tonight on the

news I heard that the Carnival Triumph, the ship we were on for five days, and

that put out to sea for a new cruise just hours after we disembarked, had a

fire in the engine room and was adrift in the Gulf! No one was injured and all

the passengers are safe but the ship will have to be towed back to Galveston. I

didn't know anyone going on board the ship, but the stewards and wait persons

we met and who befriended us are on board. May they all be safe. But please,

don’t let that deter you from taking a cruise...it’s one of the best ways to

travel.

Location:

Cottonwood Shores, TX, USA

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)