I thought I'd lighten it up a little, and get away from all that deep thinking, wading around in shallow waters.

My dad got me my first real job when I was fifteen. It wasn't my idea, but he obviously thought it was high time I didn't spend my summer idle, and I was getting too old for camp. I was going to start boarding school in the fall. Boy needed some life lessons. So he cooked it up with Mrs. McCartney to hire me at her garage.

Some back story. Hazel McCartney and her husband Sewell left a small town in Maine and came down to Cambridge, Mass., during the Depression. They started their business on a shoestring, but made out. Then, a few years later, from what I hear, he decided he didn't like it in the city, and went back upcountry. She stayed.

S.H. McCartney's was a fixture, outside of Harvard Square. Everybody used it for car repair, and I remember getting air for my bike tires there from the time I was off training wheels. It wasn't an unfamiliar work environment. What was unfamiliar was work.

The shop floor itself was guys, entirely guys, and tough working-class guys, Irish, Italians, Polacks. [Years later, I wrote a story called "The Blue Mirror," and used one of my personal heroes, Stanley Kosciusko, who survived the bombing raids over the Ploesti oil fields in WWII, but cancer killed him, in the end. He was the body man, not a mechanic. It's a special skill set.] They didn't treat me too rough, even though I was the FNG, and just a kid, but they didn't baby me along, either. Nobody sent me to find a left-handed wrench, or some other tom-fool errand, but they expected me to sink or swim, and get up to speed. I thought they were awesome. It was the first time I'd been put in a situation where everybody knew their business back to front. They were professionals. They could lean down and listen to an engine running, and tell you all it needed was a new set of points. To me, it was a different world.

Now. Mrs. McCartney. I think, by then, she must have been into her early sixties. And here in her shop, you have this overwhelmingly male presence, all of them people who knew their stuff, but I never heard a disrespectful word from any of them, in or out of her hearing. She came to work at 7 AM, and slipped into a white duster. We had a uniform service, so all the guys wore coveralls with their name over the pockets. I got a set of my own, too, after a month on the job. The boss had her name stitched to her uniform. It read MRS. MAC, and that's what we all called her. She was, maybe, the iron hand in the velvet glove, or more to the point, the iron hand in the iron glove. I admired her beyond words. If you asked me who my first and strongest role model was, I'd have to say it was her.

Now, a digression. Or not. Anybody who's ever run a small business knows that it stays afloat on endless paperwork, invoicing and payroll, tax liabilities, all that crap. So aside from the mechanics working on the floor, and the body shop, and the parts department, the nuts and bolts, no pun intended, there was an office upstairs, and it was run by a gal who was the first true Butch I'd ever consciously met. Not that I snapped to it, then. She was a chain-smoker, Camels or Luckies, and she smoked them down until the ashes fell behind her teeth. She was an intimidating figure. I didn't know at the time that she and Mrs. Mac owned a house together. What used to be called a Boston marriage. I have no idea what went on between the two of them, outside of work, and it's none of my business. The point is that Mrs. Mac trusted this woman absolutely, to handle the money end. Their relationship, in that sense, was transparent.

So we fast-forward about ten years. I'd dropped out of college, I'd been in the military, I'd had my heart broken. I slink back to my hometown, Cambridge, Mass., licking my wounds. I take my mom's car into Mrs. Mac's, and the first thing, she offers me a job. She needs a front-end guy. I say yes, don't even think about it. She wants somebody who knows their ass from a hole in the ground, and I need a comfort zone. I start the next day.

Here's the deal. Every morning I come in at 7, and take over from the night guy, Harry Truman, who's there to keep things safe. ('Mr. Truman.' she calls him, carefully formal. The only black guy on the payroll. Not somebody who tugs his forelock, either. Along with Stanley, another of my private heroes.) Then the shop foreman hands me the day's tickets. Out front, we got maybe fifty cars, stacked up with only enough room to get to the gas pumps. My job is to rearrange those cars. Which ones go to the tire station, who's in for an oil change, who has to get on the lift for a muffler job. You know that little hand-held puzzle, from when we were kids? It's a plastic pad, with thirty-five tiles, and thirty-six spaces, so you've only got one empty space, and you have to shuffle the tiles around and get 'em in order. Sort of a two-dimensional Rubik. Not all that hard. But that's what I did in the parking lot, first thing in the morning, shift the cars and line up the customers for the shop, by work order. Who's on First? Not rocket science, but attention to detail. If a hole opened up on the shop floor, you wanted to fill it.

Mind you, this place was right on Mass. Ave., and there were gas pumps, so I'm the gas jockey, too, and basically your first point of contact. I'm representing, not my strong point, I admit. I caught some odd details. There was a grocery store, right next door, for example, and this woman comes, threading between the cars, and she's got a three-year-old boy in tow, baffled, and a girl, six or seven, who's scrubbing her eyes and collapsing in tears. Not hysterics, although the mom's near crazy. "I think she must have touched a pepper in the supermarket, and rubbed her eyes." I reach over a car and scoop the kid up and get her into the bathroom, and have her splash water in her face. The mom is right behind me, wringing her hands. It passes. I give the little girl some soap, to clean up. Everybody takes a deep breath. The kid, her face red, a little embarrassed, I guess, thanks me. Her brother is looking at me with enormous eyes, like, What just happened? Their mom is of course relieved. Not that serious. The kids are okay, nobody's delinquent, she's not a bad mother, her daughter's not going to go blind. Today's good deed.

Then there was the bum.

Because we were on the main drag, there was a lot of foot traffic, as well as cars going by. College kids, hippies, street musicians, office workers, stoners, who knows? Jeans and tie-dyed T-shirts the fashion. It was a parade. Hell, it was a zoo. I mean, come on, this was back in the day, everybody smoking dope and careless of the future. We thought we were the heroes of the Revolution.

And this one particular morning, a guy shows up, somewhere past fifty, but hard to tell, the mileage on his tires. Burned brown as walnut, clothes worn but clean, not walking wounded. You get a read on people. He might have been down on his luck, but he had self-respect. He asks me if he can use the Men's Room.

Well, okay. I hesitated. And then I thought, gimme a break. He's just a guy on his uppers. I say sure.

Goes in, takes a leak, cleans up after himself, washes his face, doesn't piss on the seat. We're cool. He comes out, thanks me for the kindness, and then as he's going out the door, he turns back and flashes me this enormous grin.

"It's a great life if you don't weaken," he says.

I think about that encounter. I think about it a lot. What if you didn't have a pot to piss in, or a window to throw it out of? And what if some kid in a gas station paid you the courtesy of treating you like you weren't some piece of gum on his shoe? You could be there.

It's a great life if you don't weaken.

DavidEdgerleyGates.com

25 June 2014

Skid Marks (for Carole Langrall)

24 June 2014

Kill My Landlord, Kill My Landlord (or How Eddie Murphy Sparked a PI Novel)

by Jim Winter

by Jim Winter

One afternoon in 1999, I was watching reruns of Saturday Night Live from when Eddie Murphy was the only reason to watch the show. Outside, my upstairs neighbor was up on a ladder doing some balcony work for our landlord. On SNL, Eddie Murphy began doing one of his most famous bits as a prison poet. The poem had the refrain "Kill my landlord, kill my landlord." Most people would just laugh and say, "Wow. Eddie Murphy used to be funny before Pluto Nash." And that thought did cross my mind.

But I also wondered if my landlord instead of my neighbor did the balcony work, could one getting away with shoving him off the ladder?

Kill my landlord, kill my landlord.

Naturally, I started scribbling notes. What was the landlord's name? (Not mine. I usually dealt with his wife, who was a very nice lady.) How do you shove him off the ladder and make it look like an accident? I spent the evening banging out the basics of a story and had 14 pages of an outline by the time I got shut down the computer. I even tacked on Eddie Murphy's poem at the beginning for inspiration.

Kill my landlord, kill my landlord.

All this went into my first novel, Northcoast Shakedown. I guarantee when people finally read it, they weren't thinking of Eddie Murphy. They might have wondered if my landlord looked over his shoulder or if I had a blonde neighbor who entertained me with chicken wings. (I had a blonde neighbor. Never saw her eat wings.)

It's one of the more unusual places someone has found an idea for a story. Pink Floyd's The Wall might be the most odd. The classic album sprang from an incident where Roger Waters spat on an obnoxious fan. It wasn't even the most memorable incident that night. (Waters hurt his foot later horsing around backstage.)

I talked before here about where stories come from. There were the usual sources: Snatches of conversion, ripping from the headlines, what if scenarios. It's these strange moments that grab a writer's mind that are the most interesting. Sometimes, there's not even a story in the beginning. There are only disparate elements that a writer finds interesting and keeps mixing them up until he has a story. Think Caddyshack. The original story about a caddy trying to get a scholarship is still there as a polite suggestion, but Harold Ramis had no clue what his movie was about until he realized the real conflict was Bill Murray vs. the gopher.And that was after the movie was finished.

One afternoon in 1999, I was watching reruns of Saturday Night Live from when Eddie Murphy was the only reason to watch the show. Outside, my upstairs neighbor was up on a ladder doing some balcony work for our landlord. On SNL, Eddie Murphy began doing one of his most famous bits as a prison poet. The poem had the refrain "Kill my landlord, kill my landlord." Most people would just laugh and say, "Wow. Eddie Murphy used to be funny before Pluto Nash." And that thought did cross my mind.

But I also wondered if my landlord instead of my neighbor did the balcony work, could one getting away with shoving him off the ladder?

Kill my landlord, kill my landlord.

Naturally, I started scribbling notes. What was the landlord's name? (Not mine. I usually dealt with his wife, who was a very nice lady.) How do you shove him off the ladder and make it look like an accident? I spent the evening banging out the basics of a story and had 14 pages of an outline by the time I got shut down the computer. I even tacked on Eddie Murphy's poem at the beginning for inspiration.

Kill my landlord, kill my landlord.

All this went into my first novel, Northcoast Shakedown. I guarantee when people finally read it, they weren't thinking of Eddie Murphy. They might have wondered if my landlord looked over his shoulder or if I had a blonde neighbor who entertained me with chicken wings. (I had a blonde neighbor. Never saw her eat wings.)

It's one of the more unusual places someone has found an idea for a story. Pink Floyd's The Wall might be the most odd. The classic album sprang from an incident where Roger Waters spat on an obnoxious fan. It wasn't even the most memorable incident that night. (Waters hurt his foot later horsing around backstage.)

I talked before here about where stories come from. There were the usual sources: Snatches of conversion, ripping from the headlines, what if scenarios. It's these strange moments that grab a writer's mind that are the most interesting. Sometimes, there's not even a story in the beginning. There are only disparate elements that a writer finds interesting and keeps mixing them up until he has a story. Think Caddyshack. The original story about a caddy trying to get a scholarship is still there as a polite suggestion, but Harold Ramis had no clue what his movie was about until he realized the real conflict was Bill Murray vs. the gopher.And that was after the movie was finished.

23 June 2014

Are You A Cop?

by Jan Grape

People often ask if I am or was ever a police officer since I write a policewoman series. My answer is "No." However, in 1991 I took some classes offered by the Austin Police Department. It was the Austin Citizen's Police Academy. The training was a four-hour, once a week for twelve weeks program, set up mainly for people wanting to belong to their Neighborhood Watch Program. When I filled out my application for the classes I said I wrote mysteries and was interested to learn more about policing in order to write more realistically. That got me into the classes and I enjoyed them a great deal. So much so, that I encouraged my husband to attend, which he did and I also joined the Citizen's Police Academy Alumni Association or the CPAAA.

People often ask if I am or was ever a police officer since I write a policewoman series. My answer is "No." However, in 1991 I took some classes offered by the Austin Police Department. It was the Austin Citizen's Police Academy. The training was a four-hour, once a week for twelve weeks program, set up mainly for people wanting to belong to their Neighborhood Watch Program. When I filled out my application for the classes I said I wrote mysteries and was interested to learn more about policing in order to write more realistically. That got me into the classes and I enjoyed them a great deal. So much so, that I encouraged my husband to attend, which he did and I also joined the Citizen's Police Academy Alumni Association or the CPAAA.The instruction was comprehensive and each week different departments were covered by either the head of the department or the next person in charge. The sessions covered Communications, Patrol, SWAT, Robbery Homicide, Fire Arms, Fraud, Canine Units, and General Training. Each session consisted of lectures, demonstrations, tours and the last session was a riding in a patrol car with an officer for a ten hour shift. Mine was a fairly easy shift but I did soon realize that every single call an officer responded to could be dangerous. Even the ones that were supposed to be nothing more than a suspicious vehicle parked on a neighborhood street.

The CPA's slogan was "Understanding through Education." The goal was to provide enough information to help dispel misconceptions about policing and establish rapport between citizens and the police officers. Besides the knowledge and understanding I gained, I also met several officers I was able to call on when I needed detailed information on a particular subject.

Once the training program was complete we had an actual graduation ceremony and were given a diploma. We were then able to join the Alumni Association if we wished to do so. I did and one of the perks for alumni members we were called out during at least one of the regular police academy sessions to be a "bad guy" in a practical exercise training. To me, that was great fun to pretend to be a scumbag, and really get a cadet into a situation. They knew they weren't gong to actually get hurt but we could rag on them and cuss them out. The only time in my life I was able to cuss out a police officer and get away with it. I had a training officer tell me to get really mouthy with some cadets to see how they would react… especially if there was a cadet the T.O. needed to be sure that cadet would be able to keep their cool and handle the situation correctly.

In my book, Dark Blue Death, I wrote the first chapter of a scene that took place almost word for word in a training session. My training officer that day was a outgoing, very personable female officer who had been on the Austin police force for several years and in fact, was one of the first female patrol officers. She told me "war stories" of stopping a car for speeding and putting her police hat on. Her hair was pulled back in a pony tail and she had a bit of a deep voice. The culprit would be shocked to discover she was a woman. Sometimes walking up to the car, with a female driver, that female would be all ready to flirt with the officer, maybe pulling her skirt up a bit to show her legs. The idea being to get out of getting a speeding ticket. More than one driver showed real disappointment when the officer stopping her was female.

I actually went on a drug buy with an officer who told her Confidential Informant that I was a DEA agent helping on a special task force. The CI was given money by my police officer buddy and told what to buy. The CI went inside the suspect house and made the buy. The CI came back out with the drug and was sent on his way. The police officer put the crystal meth rock in an evidence bag, labeled and dated it, then she and I returned to headquarters and she showed me how they stored the drug in the evidence locker, marking the time and place and the action. It was all totally fascinating to me and still is. Unfortunately, it's nearly impossible to get to accompany an officer in that manner nowadays. The CPA still exists but now is a fourteen week program and a number of the alumni work in a volunteer capacity where needed.

To be honest, I don't think I'd like to be a police officer but it's fun to write about being one. Strangely enough, I was writing Private Eye short stories before I wrote my first Zoe Barrow novel. And even after becoming an alumni of the citizen's police academy I still was working on a PI novel. I was out at the academy, getting ready to participate in a practical exercise when this policewoman character began talking to me. Yes, I'm one of the weird ones who often hear voices in my head. My characters start talking. Zoe began talking and she was very determined that I tell her story. So I did. The first is Austin City Blue, and as I mentioned earlier, that Dark Blue Death was the second.

Oddly enough when my husband passed away and I had a number of health problems, Zoe quit talking. She does have one more book to tell and it was half-way complete when my life changed. It's even got a great title, Broken Blue Badge. I just have a strange feeling that she's on the edge of my conscious and will show up one day soon and begin taking again.

Until then, I'll keep seeing all y'all fairly regularly.

Location:

Cottonwood Shores, TX, USA

22 June 2014

There was a Crooked Village

by Leigh Lundin

Little Stomping

Picture a village whose reason for being is a criminal enterprise. Imagine its entire raison d’être, its very existence hinges upon fleecing the public. Typical of such towns, as many as one in fifteen to twenty of residents– men, women, children and chickens– are part of its politico-judicial machinery: crooked cops, municipal machinators, and corrupt clerks.

And not ordinary crooked cops, but heavily armed with the latest in high-power assault weaponry and shiny pursuit vehicles. Police– poorly trained but still police– yet some may not have been certified officers at all. One fancied himself Rambo and stopped tourists with an AR-15 slung across his chest like that inbred couple in Open Carry Texas.

Village authorities arbitrarily moved town limit signs beyond the actual town’s boundaries in a bid to increase exposure to radar patrol… and revenues. When cops sat in lawn chairs aiming their radar guns and sipping from their open containers, they turned a blind eye to the citizens who dried their marijuana in the convenience store’s microwave. Oh, and those shiny police cars? The town often didn’t bother to insure them, this in a village where the police department wrote more tickets than Fort Lauderdale but still outspent its budget.

Speed Trap

Set this supposition aside for the moment.

When I was a kid who couldn't yet drive, a short story left an impression on me. The plot centered around a man traveling to Florida who was caught in a small town speed trap. The police tossed him in jail.

Andy Griffith they weren't: they kept him imprisoned as the authorities systematically drained his assets like a spider sucks juices from a fly. Who do you turn to when the law is corrupt?

Florida sunshine has always attracted northerners during the icy winter months. In the first half of the 20th century, snowbirds filtered south through the highways and byways of America. Before the 1950s, towns and villages in the arteries of early tourism discovered they could make money fleecing tourists passing through their area.

Some places in the Deep South considered northern travelers carpetbaggers and therefore fair game. Even so, town fathers and others found it easy to offset moral compunctions when considering the sheer profit involved. Could they help it if a Yankee ran a stop sign obscured by tree branches or failed to notice the speed limit abruptly changed from 55 to 25?

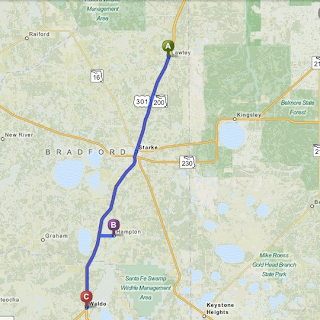

Where’s Waldo?

In the tiny towns of Lawtey, Hampton, and Waldo, that’s exactly what happens as the speed limits bounce every block or so from 55 to 30 to 45 to 25 and back again. If you have the time and patience, you might try locking your cruise control in at 25mph, hoping to beat the system. But they have an answer for that too– tickets for failing to maintain a safe speed.

In the early 1990s, it dawned on Hampton that nearby US 301 was an untapped piggy bank with the emphasis on piggy. The highway had been a source of resentment when it passed within a few hundred metres of the town limits, but devious minds found a way to make the road pay. The village annexed a strip of land 420 yards (384 metres) along the federal highway and began hiring candidates for police officers. Hampton’s speed trap was born.

(See maps below.)

In a state with a governor who committed the largest Medicare/Medicaid fraud in history, it takes a lot to outrage the Florida Legislature, but over time, Hampton succeeded. Their downfall started when they had the audacity to ticket State Representative Charles van Zant. Thanks to him, Florida lawmakers drew up plans to revoke the city's charter and revert the village to an unincorporated plat of county land.

The events that set Hampton above (or below?) its speed trap neighbors, Lawtey and Waldo, is the corruption that took place off the highway. The village can’t account for monies in the high six-figures while at the same time failing to provide basic maintenance and repairs. Under one free-spending family that ‘managed’ the little city, it ran up large debts at local stores and on the municipal credit card.

While the town failed to properly bill residents for the water utility, the clerk collected cash– Sorry, no receipts. The water department can’t reconcile nearly half of the water actually distributed, telling auditors the records were “lost in a swamp.” And if residents complained about inefficiency and corruption, their water supply was cut off altogether, prompting Bradford County Sheriff Gordon Smith to refer to the situation as “Gestapo in Hampton.”

As CNN suggested, the town became too corrupt even for Florida to stomach. State and federal auditors agreed and wheels started turning to unincorporate the town and strip it of its charter. The road to perdition seemed inevitable.

Road to Recovery

But not everyone saw it that way. Once corrupt authorities slunk back into the shadows, good citizens of Hampton stepped forward. A former clerk took over the reins. A new resident made plans to run for mayor, replacing the current mayor who resigned from his jail cell. Volunteers put together a plan to bring the town into compliance and moreover, they acted upon it. Among other things, the town plans to de-annex the strip of land encompassing US 301 although the ‘handle’ part of the town’s griddle shape will remain.

At present, efforts to revoke the town’s charter remain in abeyance and it looks like the town may have saved itself. We can only wish legislators had the political gumption to rid the state of speed traps altogether in places like Waldo, Lawtey, and Windemere.

Short Story Bonus

And, in case you were wondering, Jacksonville is probably not named after Shirley Jackson, despite her [in]famous short story about a small town. Read it on-line | download eBook PDF | download audiobook.

Picture a village whose reason for being is a criminal enterprise. Imagine its entire raison d’être, its very existence hinges upon fleecing the public. Typical of such towns, as many as one in fifteen to twenty of residents– men, women, children and chickens– are part of its politico-judicial machinery: crooked cops, municipal machinators, and corrupt clerks.

And not ordinary crooked cops, but heavily armed with the latest in high-power assault weaponry and shiny pursuit vehicles. Police– poorly trained but still police– yet some may not have been certified officers at all. One fancied himself Rambo and stopped tourists with an AR-15 slung across his chest like that inbred couple in Open Carry Texas.

Village authorities arbitrarily moved town limit signs beyond the actual town’s boundaries in a bid to increase exposure to radar patrol… and revenues. When cops sat in lawn chairs aiming their radar guns and sipping from their open containers, they turned a blind eye to the citizens who dried their marijuana in the convenience store’s microwave. Oh, and those shiny police cars? The town often didn’t bother to insure them, this in a village where the police department wrote more tickets than Fort Lauderdale but still outspent its budget.

|

| First of three speed traps in a 20 mile stretch of US 301. AAA believed to sponsor sign. |

Set this supposition aside for the moment.

When I was a kid who couldn't yet drive, a short story left an impression on me. The plot centered around a man traveling to Florida who was caught in a small town speed trap. The police tossed him in jail.

Andy Griffith they weren't: they kept him imprisoned as the authorities systematically drained his assets like a spider sucks juices from a fly. Who do you turn to when the law is corrupt?

Florida sunshine has always attracted northerners during the icy winter months. In the first half of the 20th century, snowbirds filtered south through the highways and byways of America. Before the 1950s, towns and villages in the arteries of early tourism discovered they could make money fleecing tourists passing through their area.

| |

| Lawtey, Hampton, Waldo speed traps | |

| |

| US 301: Jacksonville ↔ Gainesville Atlantic at right, Georgia border at top |

Some places in the Deep South considered northern travelers carpetbaggers and therefore fair game. Even so, town fathers and others found it easy to offset moral compunctions when considering the sheer profit involved. Could they help it if a Yankee ran a stop sign obscured by tree branches or failed to notice the speed limit abruptly changed from 55 to 25?

Where’s Waldo?

In the tiny towns of Lawtey, Hampton, and Waldo, that’s exactly what happens as the speed limits bounce every block or so from 55 to 30 to 45 to 25 and back again. If you have the time and patience, you might try locking your cruise control in at 25mph, hoping to beat the system. But they have an answer for that too– tickets for failing to maintain a safe speed.

In the early 1990s, it dawned on Hampton that nearby US 301 was an untapped piggy bank with the emphasis on piggy. The highway had been a source of resentment when it passed within a few hundred metres of the town limits, but devious minds found a way to make the road pay. The village annexed a strip of land 420 yards (384 metres) along the federal highway and began hiring candidates for police officers. Hampton’s speed trap was born.

(See maps below.)

In a state with a governor who committed the largest Medicare/Medicaid fraud in history, it takes a lot to outrage the Florida Legislature, but over time, Hampton succeeded. Their downfall started when they had the audacity to ticket State Representative Charles van Zant. Thanks to him, Florida lawmakers drew up plans to revoke the city's charter and revert the village to an unincorporated plat of county land.

|

| Hampton with annex |

|

| Hampton |

While the town failed to properly bill residents for the water utility, the clerk collected cash– Sorry, no receipts. The water department can’t reconcile nearly half of the water actually distributed, telling auditors the records were “lost in a swamp.” And if residents complained about inefficiency and corruption, their water supply was cut off altogether, prompting Bradford County Sheriff Gordon Smith to refer to the situation as “Gestapo in Hampton.”

As CNN suggested, the town became too corrupt even for Florida to stomach. State and federal auditors agreed and wheels started turning to unincorporate the town and strip it of its charter. The road to perdition seemed inevitable.

Road to Recovery

But not everyone saw it that way. Once corrupt authorities slunk back into the shadows, good citizens of Hampton stepped forward. A former clerk took over the reins. A new resident made plans to run for mayor, replacing the current mayor who resigned from his jail cell. Volunteers put together a plan to bring the town into compliance and moreover, they acted upon it. Among other things, the town plans to de-annex the strip of land encompassing US 301 although the ‘handle’ part of the town’s griddle shape will remain.

At present, efforts to revoke the town’s charter remain in abeyance and it looks like the town may have saved itself. We can only wish legislators had the political gumption to rid the state of speed traps altogether in places like Waldo, Lawtey, and Windemere.

Short Story Bonus

And, in case you were wondering, Jacksonville is probably not named after Shirley Jackson, despite her [in]famous short story about a small town. Read it on-line | download eBook PDF | download audiobook.

Labels:

corruption,

Florida,

fraud,

Leigh Lundin,

speed traps

Location:

Hampton, FL, USA

21 June 2014

Ruminations of a Senior Citizen

by John Floyd

NOTE: Please join me in welcoming my friend Herschel Cozine as our guest blogger. Herschel is well known to the writers and readers of both SleuthSayers and its predecessor, Criminal Brief, as an accomplished author of short mystery fiction. His credits include AHMM, EQMM, Woman's World, and many other publications, and his book The Humpty Dumpty Tragedy was nominated by Long and Short Reviews for Best Book of 2012. (I'm currently on the road and will be back in two weeks--meanwhile, I've left you in good hands. Herschel, thanks again!)

What has that to do with writing? When I was young and innocent--well, young anyway--I had the irresistible urge to write. As fellow writers, you need no explanation. But I didn't write for any specific market or, for that matter, for any market at all. I wrote because it was something I had to do. I got a certain amount of recognition for this hobby, or whatever word you care to use, when I was in high school. Class writing projects in English usually resulted in my effort being used by the teacher as a model. One of my class projects found its way into the yearbook. It felt good to get this recognition, but in high school no self-respecting boy would admit it. A football hero? Yes. Drag racing champion? Certainly. Writer? Are you kidding me?

What has that to do with writing? When I was young and innocent--well, young anyway--I had the irresistible urge to write. As fellow writers, you need no explanation. But I didn't write for any specific market or, for that matter, for any market at all. I wrote because it was something I had to do. I got a certain amount of recognition for this hobby, or whatever word you care to use, when I was in high school. Class writing projects in English usually resulted in my effort being used by the teacher as a model. One of my class projects found its way into the yearbook. It felt good to get this recognition, but in high school no self-respecting boy would admit it. A football hero? Yes. Drag racing champion? Certainly. Writer? Are you kidding me?

-- John Floyd

In the past few months several of you have commented on the fact you are getting old. Not fifty or sixty type oldies. Let's face it, that's kid stuff. We are talking "old." It should be a four-letter word. Maybe that's why the British put an "e" on the end. On the other hand, with age comes wisdom, or so the saying goes. Speaking from personal experience, I question that. Some people never learn.

But that is not the purpose of this discussion.

I have a birthday looming on the horizon. Another one. That's the third one this year, or so it seems. I suppose I should be grateful. After all, studies have shown that birthdays are good for you. The more you have the longer you live. But I'm at a point in my life where they start to hurt.

I have a T-shirt that reads: "I plan to live forever. So far, so good." An old Steven Wright joke. But at times I feel I have accomplished that goal.

There is no polite way to put it. I am an old man. It certainly is nothing to be ashamed of. It happens to everyone if they are lucky. But it is a sobering time of life, a time when one comes face to face with his mortality. I recently had a financial guru give me a tip on an investment that would double in value in five years. I turned him down. I am no longer a candidate for long term investments.

What has that to do with writing? When I was young and innocent--well, young anyway--I had the irresistible urge to write. As fellow writers, you need no explanation. But I didn't write for any specific market or, for that matter, for any market at all. I wrote because it was something I had to do. I got a certain amount of recognition for this hobby, or whatever word you care to use, when I was in high school. Class writing projects in English usually resulted in my effort being used by the teacher as a model. One of my class projects found its way into the yearbook. It felt good to get this recognition, but in high school no self-respecting boy would admit it. A football hero? Yes. Drag racing champion? Certainly. Writer? Are you kidding me?

What has that to do with writing? When I was young and innocent--well, young anyway--I had the irresistible urge to write. As fellow writers, you need no explanation. But I didn't write for any specific market or, for that matter, for any market at all. I wrote because it was something I had to do. I got a certain amount of recognition for this hobby, or whatever word you care to use, when I was in high school. Class writing projects in English usually resulted in my effort being used by the teacher as a model. One of my class projects found its way into the yearbook. It felt good to get this recognition, but in high school no self-respecting boy would admit it. A football hero? Yes. Drag racing champion? Certainly. Writer? Are you kidding me?

Eventually, after college, I was told by someone that I should try my hand at writing for--how crass--money. I had been writing poems and stories for children, but never submitted them to magazines. The thought was intriguing. I found an ad in a writing magazine about a contest being sponsored by the Society of Children's Book Writers. First prize was $100, a princely sum at that time. I had just completed a children's story, in verse. So I typed it up, put it in the standard package of the day--a manila envelope--and sent it in. Lo and behold, it won!

I was hooked. For several years I wrote and sold a fair number of poems and stories to the children's magazines of the day. But, being a big fan of adult mysteries, I eventually turned my attention to writing them. My first success in that arena was a Department of First Stories sale to Ellery Queen.

I won't bore you with any further successes and failures. I have had some of the former and more than my share of the latter. I mention them only as a prelude to what I really want to say.

I have reached a stage in my life where writing for money is no longer important. Oh, I won't turn down a check if some editor wants to buy my story. But this is now merely a fringe benefit and not the main purpose for continuing to write. (Come to think of it, it never was.)

What is important to me is to have the respect of those who take the time to read my efforts. I particularly cherish the recognition afforded me by other writers. They, after all, are fellow travelers who know and appreciate the slings and arrows of this business. They have hit the same bumps, felt the sting of rejection and the giddiness of acceptance. You, my friends, matter.

As I said in the beginning, I am an old man. I no longer write with the fervor and eagerness of youth. Ideas that used to come in torrents now dribble in grudgingly. I continue to write. But it is not the same. I am more critical of my work, often deleting it after several attempts to make it work. But enough of it remains to keep me going. And that will never change. I don't question why. All I know is that I am a writer; whether a good one or not I leave for others to decide. But a writer--a true writer--cannot quit. To paraphrase, neither sleet or snow or dark of night, or old age, will keep a writer from his word processor. And now to bed.

NOTE: A special thanks to Jim Williams, a lifelong friend, for his cartoon. In addition to being a cartoonist, Jim is a fellow writer. His book, Cattle Drive, published by High Noon Press, has just been released and is available on Amazon.

20 June 2014

....and Handlers

by R.T. Lawton

(cont'd from two weeks ago)

If an agency doesn't have good procedures and controls in place for their assets and their Handlers, then they are looking for trouble in an area where trouble is easily found. Every agency now probably has its own system and policies in place, but the basics are generally the same, so let's take a look at them.

For security, it's best to give the informant, or asset, a code number to be used in all activity and debriefing reports. Within this code number file should be the informant's fingerprints, which may also help ensure he is who he says he is; a personal history or background, info needed to check up on him now and maybe in the future if he goes on the run; a records check to find any crimes charged with or convicted of in the past; a color photo; and a debriefing report to determine what value the informant may have to your agency.

Also in this file, it would be smart to have a signed copy of the Informant Agreement. This document lays out the parameters of what the informant will and will not do, such as realizing that he is NOT law enforcement, nor is he an agency employee. He also agrees not to break the law, unless specifically authorized, else face possible prosecution if caught.

Special permission is usually needed from some authority before a Handler can use a juvenile, a two-time felon, a drug addict, someone on parole or probation, a current defendant or a prison inmate. Doesn't mean a Handler can't use people in these categories, it merely means that extra steps must be taken and permission from the proper authority is required before use. Why? Because inherent problems need to be addressed before these people can be activated. For instance, use of a parolee requires permission of the affected parole or probation agency, a defendant requires permission of the prosecuting attorney and use of an inmate requires permission of that prison's authorities. The spy world has their own policies on restrictions and categories, which are considerably looser.

Two Handlers should be present at every meeting with an asset in order to prevent false accusations of wrongdoing on the part of the Handler, especially during those times when a Handler is paying funds to the asset. (This may not be feasible in some spy situations.) Informants are paid out of agency funds (or reward money) with paperwork and signatures to document the payments.

Handlers should not engage in personal socializing, joint business ventures or romantic entanglements with the asset, nor should they receive gifts from the asset. I think you can figure out some of the bad possibilities for these situations.

Informants should be searched before and after each controlled meeting with a targeted individual, thus if the informant brings back evidence from that meeting, the presumption is that evidence came from the target, not planted by the informant.

The asset should be debriefed at least every ninety days for new intelligence, else placed on inactive status. Supervisors should review informant status and manage controls.

The Handler should try to independently verify any information received from an informant to ensure it is good intelligence.

NOTE: Private investigators are not held to the same high standards as law enforcement, while spy agencies may have exigent circumstances allowing looser controls and procedures for use of informants.

How do things go bad? Ask the FBI agent who went to prison from the way he handled mobster Whitey Bulger as an informant.

And then there was the state agent who got his informant pregnant, lost his job and had to testify to all those facts during a defendant's subsequent trial in federal court.

We sometimes had one informant buy from another informant who was trafficking while working for us. The second guy went to prison.

Knew a state informant who without his Handler's knowledge, wired up his own house with hidden cameras and microphones and proceeded to act like his favorite movie character when dealing with other criminals.

One informant with a felony record which prevented him from carrying a gun, we soon discovered would sometimes show up at our meetings with his girlfriend who was carrying two concealed automatics.

I think you're starting to see why tight controls are necessary, cuz things can go really bad in a heartbeat. All of which could make good fodder for a crime novel. So, if you get any good writing ideas from the above, feel free to use them.

If an agency doesn't have good procedures and controls in place for their assets and their Handlers, then they are looking for trouble in an area where trouble is easily found. Every agency now probably has its own system and policies in place, but the basics are generally the same, so let's take a look at them.

For security, it's best to give the informant, or asset, a code number to be used in all activity and debriefing reports. Within this code number file should be the informant's fingerprints, which may also help ensure he is who he says he is; a personal history or background, info needed to check up on him now and maybe in the future if he goes on the run; a records check to find any crimes charged with or convicted of in the past; a color photo; and a debriefing report to determine what value the informant may have to your agency.

Also in this file, it would be smart to have a signed copy of the Informant Agreement. This document lays out the parameters of what the informant will and will not do, such as realizing that he is NOT law enforcement, nor is he an agency employee. He also agrees not to break the law, unless specifically authorized, else face possible prosecution if caught.

Special permission is usually needed from some authority before a Handler can use a juvenile, a two-time felon, a drug addict, someone on parole or probation, a current defendant or a prison inmate. Doesn't mean a Handler can't use people in these categories, it merely means that extra steps must be taken and permission from the proper authority is required before use. Why? Because inherent problems need to be addressed before these people can be activated. For instance, use of a parolee requires permission of the affected parole or probation agency, a defendant requires permission of the prosecuting attorney and use of an inmate requires permission of that prison's authorities. The spy world has their own policies on restrictions and categories, which are considerably looser.

Two Handlers should be present at every meeting with an asset in order to prevent false accusations of wrongdoing on the part of the Handler, especially during those times when a Handler is paying funds to the asset. (This may not be feasible in some spy situations.) Informants are paid out of agency funds (or reward money) with paperwork and signatures to document the payments.

Handlers should not engage in personal socializing, joint business ventures or romantic entanglements with the asset, nor should they receive gifts from the asset. I think you can figure out some of the bad possibilities for these situations.

Informants should be searched before and after each controlled meeting with a targeted individual, thus if the informant brings back evidence from that meeting, the presumption is that evidence came from the target, not planted by the informant.

The asset should be debriefed at least every ninety days for new intelligence, else placed on inactive status. Supervisors should review informant status and manage controls.

The Handler should try to independently verify any information received from an informant to ensure it is good intelligence.

NOTE: Private investigators are not held to the same high standards as law enforcement, while spy agencies may have exigent circumstances allowing looser controls and procedures for use of informants.

How do things go bad? Ask the FBI agent who went to prison from the way he handled mobster Whitey Bulger as an informant.

And then there was the state agent who got his informant pregnant, lost his job and had to testify to all those facts during a defendant's subsequent trial in federal court.

We sometimes had one informant buy from another informant who was trafficking while working for us. The second guy went to prison.

Knew a state informant who without his Handler's knowledge, wired up his own house with hidden cameras and microphones and proceeded to act like his favorite movie character when dealing with other criminals.

One informant with a felony record which prevented him from carrying a gun, we soon discovered would sometimes show up at our meetings with his girlfriend who was carrying two concealed automatics.

I think you're starting to see why tight controls are necessary, cuz things can go really bad in a heartbeat. All of which could make good fodder for a crime novel. So, if you get any good writing ideas from the above, feel free to use them.

19 June 2014

The Pure Young Men

by Eve Fisher

"Squeamishness is not a woman's virtue." - Colette, Earthly Paradise, p. 92

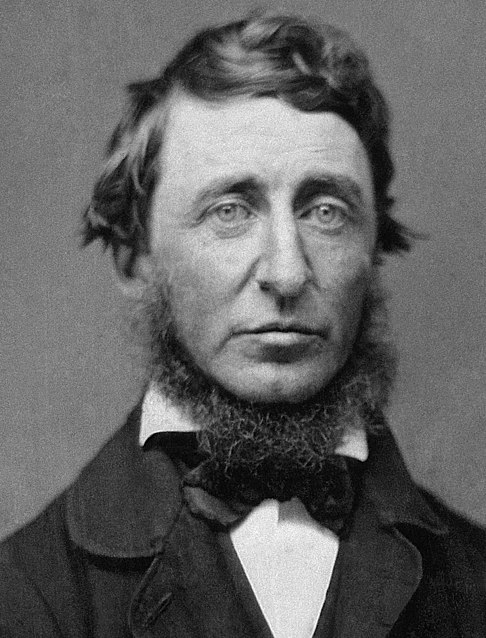

One of the main differences between men and women is that men are far more fastidious. There is nothing quite so pure as a pure-minded man: but then, he can afford to be. It's women who have to deal with a constantly recurring emission of blood and other fluids, and when the babies come it only gets worse. Men can ignore all that and turn up their noses. Men can insist on ritual purity. And there have been a lot of pure-minded men, most of them very young, who have made an awful lot of history: Bernard of Clairvaux, Maximilien Robespierre, Henry David Thoreau, and John Muir, to name three.

One of the main differences between men and women is that men are far more fastidious. There is nothing quite so pure as a pure-minded man: but then, he can afford to be. It's women who have to deal with a constantly recurring emission of blood and other fluids, and when the babies come it only gets worse. Men can ignore all that and turn up their noses. Men can insist on ritual purity. And there have been a lot of pure-minded men, most of them very young, who have made an awful lot of history: Bernard of Clairvaux, Maximilien Robespierre, Henry David Thoreau, and John Muir, to name three. And we've all known them. The pure young man is usually attractive, with a childlike air of freedom and joy that's almost irresistible. He is generally obsessively clean. He often does not swear, smoke, or drink - or, if he does, only a little, and always enjoys giving it up. (There are also those full moon nights when he goes on a binge that could, he dimly hopes, ruin his life.) He often likes to go out "into the wild" to pit himself against the forces of Nature, which he sees as a Great Pure Force. (See Thoreau and Chris McCandless.) Most women know that Nature will swat you down like a gnat if she gets the chance, and then wild animals gnaw your bones. But a Pure Young Man sees his death-defying walks into the wild as an initiation, in which he will, somehow, wring from Nature her imprimatur, and he will be made whole and eternal by his quest. (Sir Galahad was also a Pure Young Man.)

And we've all known them. The pure young man is usually attractive, with a childlike air of freedom and joy that's almost irresistible. He is generally obsessively clean. He often does not swear, smoke, or drink - or, if he does, only a little, and always enjoys giving it up. (There are also those full moon nights when he goes on a binge that could, he dimly hopes, ruin his life.) He often likes to go out "into the wild" to pit himself against the forces of Nature, which he sees as a Great Pure Force. (See Thoreau and Chris McCandless.) Most women know that Nature will swat you down like a gnat if she gets the chance, and then wild animals gnaw your bones. But a Pure Young Man sees his death-defying walks into the wild as an initiation, in which he will, somehow, wring from Nature her imprimatur, and he will be made whole and eternal by his quest. (Sir Galahad was also a Pure Young Man.) To go back to that childlike air of freedom and joy - it's so attractive. Except it's too childlike. It's all self-centered, in a way that isn't clear to those around him until they try to hold on to him in some way. Then he leaps away, like an animal from a trap, and that's the way they see human intimacy - and I'm not talking just about sexual. But, with regard to sex, they often don't do that, either, except on full moon nights in leap years. I always pity the young girl who falls for one, because 9 times out of 10 he will be Hamlet to her Ophelia and throw her away with nothing but words to remember him by. (Hamlet was another Pure Young Man.)

Anyway, Pure Young Men seem to see emotional intimacy as being as messy and defiling and unnecessary as sexual intimacy. They make wonderful friends - if your definition of a friend is someone who will stay up all night talking with you, and put up with whatever food and drink you provide. But if you want someone who will be there when the chips are down, someone who will help you out of a jam - you are going to be in trouble. IF they're still around (they have a nose for trouble and often disappear overnight), they may or may not try to help. But they also may simply not care, and tell you that your concerns are ridiculously petty.

The irony is that I think that they think that they are being a good friend, but they have no idea what that entails. They'll give their money, their material possessions, at the drop of a hat - but usually not to a friend, usually to some homeless person - but they will not give themselves on any terms except their own. They often lie or completely stonewall any questions about themselves, their past, their family, who they are. They are often very lonely. But since their loneliness is an elemental choice, it doesn't reek of that desperation that drives people away. Instead, it can be very attractive. Maybe you'll be the one who will finally crack the barrier, and become their perfect friend. Don't count on it. Their perfect friend is a dog. Or a genie in a bottle with a strong stopper, you can be their friend. The fact that you might need more will never occur to them; and if you bring it up, you will suddenly become possessive, manipulative, violating. You will be canned. Read Into the Wild, and see how often Chris McCandless abandoned friends who loved him.

And yet they're so likeable, so loveable. Probably the very best literary analysis of a Pure Young Man is Peter Pan. Children's story my ass.

Labels:

Eve Fisher,

Galahad,

Henry David Thoreau,

Robespierre

18 June 2014

Writing the Travel Writer

Special treat today. Jeff Soloway is the winner of this year's Robert L. Fish Award, given by the Mystery Writers of America to the best first mystery short story by an American author. Since "The Wentworth Letter" appeared in an e-book, he thinks he may be the first person to win an MWA writing award without appearing in print. He used to be a writer of travel guides and is now a book editor in New York. —Robert Lopresti

Special treat today. Jeff Soloway is the winner of this year's Robert L. Fish Award, given by the Mystery Writers of America to the best first mystery short story by an American author. Since "The Wentworth Letter" appeared in an e-book, he thinks he may be the first person to win an MWA writing award without appearing in print. He used to be a writer of travel guides and is now a book editor in New York. —Robert Loprestiby Jeff Soloway

Last year, Robert Lopresti and I both had stories published

in an ebook collection called Malfeasance Occasional: Girl Trouble. Rob

liked my story (and I liked his!), and when he heard that my first novel was

being published by Alibi, Random House’s new digital imprint for crime fiction,

he asked me to write about my experience. So here goes.

The Travel Writer is about a travel-guidebook

author and freelancer who accepts a free trip to a swanky hotel in Bolivia,

ostensibly to provide a glowing review of the hotel but really to investigate

the disappearance of an American journalist. When I sent the manuscript to an

editor at an independent publishing house, she told me that though the writing

was great, no one was interested in mysteries that take place in South America.

I was advised to stick to the U.S., or—if I absolutely had to get all

exotic—England or Italy.

Luckily for me, Alibi’s editors took a broader view of

the tastes of the mystery-reading public. Soon after I sent the manuscript in

to Alibi (just by email to the address on the website—I had no connection to

any of the editors and still don’t have an agent), the editor told me he liked

both the novel and the concept of a travel-writer detective. He asked for

synopses of two sequels so he could pitch the idea of a new series. I assured

him that I had a number of great ideas, and then spent the weekend holed up in

my bedroom trying to think up some great ideas.

Nothing in publishing ever works as quickly as you want

it to, so it was several months later that I finally got the good news: Alibi

wanted to sign me for three books. I was told that all of Alibi’s books would

be priced very low—the idea was that these digital originals would recapture

that market that used to be served by the little mass-market paperbacks that

were once ubiquitous in drug stores and supermarkets. I was given the choice

between a traditional publishing deal that provides a small advance against the

usual royalty for ebooks, or a less traditional one providing no advance

against a much higher royalty rate. I chose the first. Of course, now, after

publication, I have to hope that I’ve chosen wrong—that the book sells so well

that I curse myself for forsaking the higher rate. But I wanted some sort of financial

guarantee.

The editing process was a real surprise to me—remarkably,

and admirably, traditional. My editor, Dana Edwin Isaacson, printed out the

manuscript, marked it up by hand, scanned the pages, and emailed them to me. He

had suggestions both minor and major, and did a nice job of sweetening them

with compliments along the way. After a month or so at the hard labor of

revising, I resubmitted the manuscript. Dana said he loved it. His love,

however, did not prevent him from emailing several dozen more pages with

additional edits.

After Dana was done with it, the manuscript went to

Random House’s production department, where it was exhaustively copyedited. The

copyeditor checked my character’s wanderings against a map of La Paz, Bolivia

and even queried the political graffiti I quoted, among many other things. I

appreciated the back-stopping, though I did occasionally assert my privilege as

a novelist to make things up.

Several months after the copyediting I received another

small set of editor’s queries, clearly from a proofreader. I didn’t even know

they had proofreading (as opposed to one round of copyediting) for digital

books.

Now the novel is finally out. It’s priced at $2.99, which means it’s cheap enough at least to tempt a lot of readers but also that it has to sell a lot of copies to make anybody any money. Will it? The publicity people at Random House are working hard to get the word out. They sent the novel to the mystery author Christopher Fowler and received a terrific blurb in return, and they’ve launched an online marketing campaign. And of course, I personally think the novel is pretty good. The main character brings an original perspective to the traditional mystery, and the writing is funny—I hope. All I know for sure is that I wrote the thing as well as I could.

Now the novel is finally out. It’s priced at $2.99, which means it’s cheap enough at least to tempt a lot of readers but also that it has to sell a lot of copies to make anybody any money. Will it? The publicity people at Random House are working hard to get the word out. They sent the novel to the mystery author Christopher Fowler and received a terrific blurb in return, and they’ve launched an online marketing campaign. And of course, I personally think the novel is pretty good. The main character brings an original perspective to the traditional mystery, and the writing is funny—I hope. All I know for sure is that I wrote the thing as well as I could.

17 June 2014

Pictures and Words

by Stephen Ross

One of my fantasies is to be a painter. Oil on canvas. I have this vision of myself in a New York loft: A large room with a bare wooden floor, sofa, an open window with traffic sounds from the street below, open bottle of red wine, no glasses. No wall clock.

And what would I paint? People. I like a good landscape, I like a good abstract, but what moves me are paintings of people. A picture tells a thousand words, but in every face there are a million.

One of the best places to go and see paintings of people is the National Portrait Gallery in London. The NPG has nearly 200,000 paintings in its collection, and it's a great place to lose yourself in hall after hall of faces (and history).

|

| Alan Bennett (Tom Wood, 1993) |

And then you notice the power cable and plug. What has Bennett unplugged? An electric fan? A jukebox? Maybe it's symbolic. The cable extends from the viewer's point of view, so maybe Bennett's taking a break from us (i.e. he's unplugged the world). And then what exactly is concealed inside that tightly tied up brown paper bag? Lunch, or is it also perhaps symbolic of something? Secrets? Privacy?

It's a straightforward painting of a complex man and some props, but collectively they suggest the possibility of a story. If I painted, I'd definitely want to paint a story.

|

| The Betrayal (Jack Vettriano, Circa. 2001) |

Without even knowing the title, when you first see this painting you sense conflict. The man at the rear, highlighted in a background of glowing red, stares at the couple kissing in the foreground. The decor and fashions suggest a fancy club, circa. London 1950. Are the couple embracing on a dance floor? And that isn't a mere kiss, it's a full-throttle commitment. Has the man at the rear caught his lover cheating on him? He has a hand reaching inside his jacket. A gun?

When you have two or more people in a painting, you almost automatically invoke a plot. And once there's a plot in play, our mind suggests what might happen next. In this instance, a heated confrontation; it'll probably get messy. The Betrayal is like a two-dimensional piece of flash fiction.

It has to be said, of course, another viewer might glance at this painting and simply see a bored waiter staring at an amorous couple. And therein lies the fundamental difference between a written story and a painted one. A written story lays it out fairly clearly for the reader to follow. A painting only suggests and is largely open to "reader" interpretation.

|

| The Scream (Edvard Munch, 1893) |

I was lucky enough to visit an exhibition of Munch lithographs a few years ago at the Waikato Museum (a modest building on the left bank of the Waikato River in Hamilton, New Zealand). Munch made several lithographs of The Scream, and even reproduced in black and white, the image chills you to the bone when you stand in front of it. And this is despite the fact the painting's impact today has been lessened, nay flattened, by its continual referencing in popular culture (children's lunchboxes, anyone?). The painting is as ubiquitous today as the Mona Lisa.

The Scream contains what I like to find in a painting (and in a story, too): character and emotion. So along with a plot, I'd definitely want to paint characters and strong emotions.

So, I guess, if I was a painter, I'd be a figurative expressionist. Throw Lucien Freud, Francis Bacon, Edward Hopper, Frida Kahlo, Munch, the Pre-Raphaelites, and a bucket of paint into a blender and then point me at a canvas.

And why am I not a painter? That's easy: I can't paint and I can't draw. I can't even render a decent stick, let alone a figure.

But wait. There's more...

|

| The Riverboat (Eric Ross, 1997) |

I mention this because the story was inspired by a picture of a riverboat painted by my father. He painted it several years ago and it's hung on my wall ever since. My story didn't create a "plot" for his painting, but used its image as the story's centerpiece.

Be seeing you!

Labels:

Alan Bennett,

Edvard Munch,

Jack Vettriano,

National Portrait Gallery,

painters,

paintings,

plots,

Stephen Ross,

writing

Location:

Auckland, New Zealand

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)