I want to discuss another source of art that many of us have never considered. I need to step back slightly in time to 2012, shortly after I’d sold my first story to Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. Back then, I had Google alerts set to ping me anytime someone reviewed one of my books. (I have since ceased the practice. At the time I was obsessed with collecting any mention of my titles and immediately bringing them to the attention of my publishers, so they could be sure to get in their requisite number of daily yawns.)

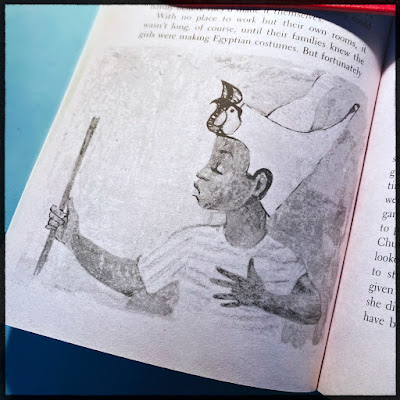

Imagine my surprise to learn one morning that one Tom Pokinko blogged about reading and enjoying my AHMM story, “Button Man.” This struck me as weird, since the story hadn’t been published yet. Turns out, Mr. Pokinko, then based in Ottawa, was an artist commissioned by AHMM to illustrate the story. He posted a “pencil” sketch of the image he intended to create, and later posted the final “pen and ink” drawing. (You’ll learn in a second the meaning of these quote marks .)

“Button Man” (AHMM, March 2013) was a historical set in the late 1950s in New York’s Garment District. It was fun to see how Mr. Pokinko illustrated rolling racks of clothing and period dress that brought the scene to life.

|

Copyright © Tom Pokinko |

Five years later, my wife and I had moved to a new house. Our office was larger than the previous one we’d shared. Finding myself staring at a fresh set of blank walls, I suddenly thought of Tom’s drawing. I wrote and asked if he would be willing to sell me the “original” drawing—that is, if he still had it and had no further use for it.

Tom gently informed me that there was no original drawing to speak of, since he (and most artists working today) create digital images, which they can more easily edit and transmit to their art directors. He offered the next best thing: a high-quality digital print on acid-free paper and archival inks that will not fade over time. He would matte the image, and sign it prior to shipping.

His only advice was to stick closely to the size of the image as it had run in the magazine. Any larger, and we’d sacrifice print resolution. Digest-size magazine pages appear stubby, but the images that run on them are necessarily designed to be somewhat tall and thin to stay out of the gutter and margins. We settled on a 8 1/2 x 11-inch print, fitted to an 11 x 17-inch matte. That’s a fairly standard frame size, by the way, which held down costs on my end.

A few years later, the cycle repeated itself. AHMM hired illustrator Tim Foley to create an image for my Sherlockian story, “A Respectable Lady” (AHMM, July/August 2017 ). If you’re a regular reader of the magazine, you will recognize Mr. Foley’s cross-hatched style immediately. He’s a longtime contributor to many publications who is over-the-moon proud of his AHMM work, which has allowed him to illustrate the work of everyone from Leo Tolstoy to Rob Lopresti! Mr. Foley maintains a running tally of all his AHMM pieces on the website, and is trying to amass a hard copy collection of all issues in which his work appeared. (That’s where you come in, author! See below for details.) I had a sense of déjà vu when I contacted Mr. Foley. He was happy to sell me a signed digital print, and offered the same advice on sizing I had heard from Mr. Pokinko. In less than a month, after a visit to his local copy shop, I had another piece for the office wall.

|

Copyright © Tim Foley |

I enjoy collecting art this way because, in a sense, the pieces were custom-made for me, or at least for whichever story of mine they illustrate. In the process, I learned that the magazine sends artists a copy of the story, which they read to conceive their image. Predictably, Dell Magazines are not high-paying illustrator’s markets, so artists are usually delighted to re-sell existing work at a reasonable price to the writer who inspired it. (Think of it as the artistic equivalent of story reprints.) In total, I spent $170 acquiring the two pieces.

If you’re thinking of acquiring AHMM or EQMM art, look for the credit line as it appears under the published image. Chances are, the artist can be easily contacted via their website.

I have not made a careful study of this, but it appears that not all digests commission art for stories. In some cases, they simply download images from stock agencies. I’ve also learned that it’s worth asking yourself if you enjoy the image in question before contacting the artist. There’s one AHMM picture that will never appear on my wall. If you don’t love it (or even like it), you’re probably better off continuing to stare at that blank wall until something desirable comes your way.

* * *

Help out an artist! Tim Foley wants to locate paper copies of all the AHMM issues that have featured his work. If you’re like me, you probably have more copies on your shelves than you know what to do with. Tim’s list is here; the dates of the missing issues are indicated in BOLD. Contact him if you have a copy you can spare. You will probably also discover that he illustrated some of your stories well!

See you in three weeks with yet another story about mysterious art!

Joe

josephdagnese.com