Anyone who writes knows—or thinks they know—what readers are expecting when it comes to characters. The Big Why.

Why is this make-believe person the way they are? What made them this way? And we writers have two tricks up our sleeve for giving readers what they want. (At least, I think there are two. Feel free to debate.)

Method #1: We can dig our heels in and stubbornly refuse to give any backstory. We set down on the page a person who is a cipher, and we let the reader determine who they are on the basis of the character’s actions.

Remember that classic scene in The Silence of the Lambs—the book, not the movie—when young Clarice Starling goes to administer a questionnaire to Hannibal Lecter? The sadistic doctor toys with her, mocking the notion that a “blunt tool” can dissect the mysteries of his personality. “Nothing happened to me, Officer Starling. I happened. You can’t reduce me to a set of influences.”

And what did poor Harris do? The more popular his Lecter became, the more he yielded to popular demand. His 1999 novel, Hannibal, hinted at Lecter’s childhood in war-torn Lithuania. His 2006 novel, Hannibal Rising, is all prequel. Critics have said that the last two books are the weakest in the series, perhaps because they fill in the blanks on Lecter’s past.

Don’t blame Harris. He did exactly what writers are expected to do when wielding Method #2: something in our character’s childhood shaped them into the person they become. Usually it’s some sort of trauma. I don’t want to get into Lecter’s. Suffice to say it’s, um, delicious?

The point is: Bad thing in past equals character.

I suppose you could play with this paradigm and change it up. Good thing in past equals character. Bad thing in one’s recent adult past—a divorce, a call to God, beating alcoholism—equals character.

HILLMAN: The principal content of American psychology is developmental psychology: what happened to you earlier is the cause of what happened to you later. That’s the basic theory: our history is our causality. We don’t even separate history as a story from history as cause. So you have to go back to childhood to get at why you are the way you are. And so when people are out of their minds or disturbed or f*cked up or whatever, in our culture, in our psychotherapeutic world, we go back to our mothers and our fathers and our childhoods. No other culture would do that. If you’re out of your mind in another culture or quite disturbed or impotent or anorexic, you look at what you’ve been eating, who’s been casting spells on you, what taboo you’ve crossed, what you haven’t done right, when you last missed reverence to the Gods or didn’t take part in the dance, broke some tribal custom. Whatever. It could be thousands of other things—the plants, the water, the curses, the demons, the Gods, being out of touch with the Great Spirit. It would never, never be what happened to you with your mother and your father forty years ago. Only our culture uses that model, that myth.

VENTURA (appalled and confused): Well, why wouldn’t that be true?

…

HILLMAN: Because that’s the myth you believe.

|

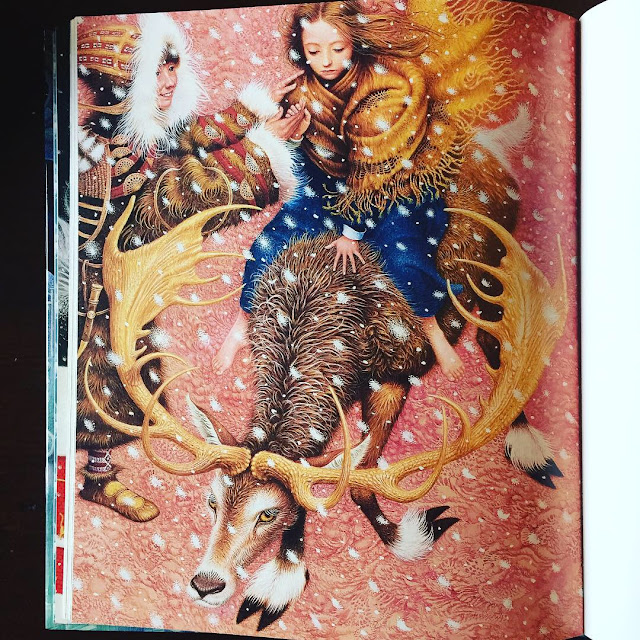

| Kristina Gadeikyte via Unsplash |

If you were creating a fictional character named Churchill or Manolete, you’d spin that person’s story using Method #2: Because he was weak speaker as a child, Churchill applied himself—and lo and behold, he became a great orator! The frightened mama’s boy overcompensated and fought bulls in manhood! Ta-da! Character tied up in a bow, fully and thoroughly explained.

Bull dinkies, says Hillman. No freaking way.

“Suppose we look at the kids who are odd or stuttering or afraid, and instead of seeing these as developmental problems we see them as having some great thing inside them, some destiny that they’re not yet able to handle. It’s bigger than they are and their psyche knows that.”

I love this concept, but I admit that I have trouble knowing how to apply it to characters I’m creating. Yes, readers have come to expect the Big Why as childhood backstory. But wouldn’t it be fun sometimes to work with a convention that breaks the mold?

Not every character is destined for greatness. But every character has the right to a greatness that is uniquely their own.

* * *

I first shared the work of Michael Ventura in my New Year’s Eve 2021 post.

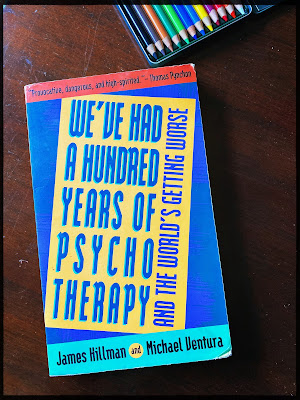

You can read more in We’ve Had a Hundred Years of Psychotherapy—And the World’s Getting Worse, by James Hillman and Michael Ventura (HarperCollins, 1992).

Best of luck on this most palindromic of Februaries!

See you in three weeks!

Joe

josephdagnese.com