I'll start by stating the obvious. This is a mystery blog, I'm a mystery writer, and most of you are (I suspect) mystery readers. Some of you are mystery writers as well--thank God we can be both. And even though the vast majority of what I write is mystery/crime, I also like writing other genres now and then. I think most of us do.

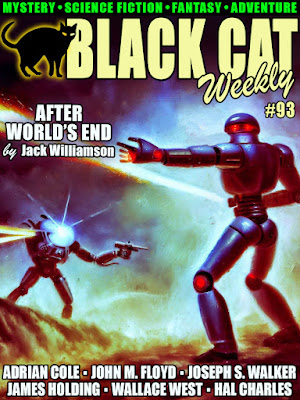

You're probably familiar by now with a publication called Black Cat Weekly. It's a product of Wildside Press, its editor/publisher is John Betancourt, and its acquisition editors are my fellow SleuthSayers Barb Goffman and Michael Bracken. One of the ways BCW is different from most of the magazines we talk about at this blog (besides the fact that it's an e-magazine and there's a new issue every week) is that it's not exclusively a mystery/crime publication. It features a wide range of stories--science fiction, mystery, fantasy, etc.

I've been fortunate enough to have some of my stories appear in Black Cat Weekly, but these past two weeks brought something new for me: I had stories in back-to-back issues. The first one, Barb's "pick" for Issue #92 on June 4 (thank you, Barb), was a lighthearted crime story called "On the Road with Mary Jo." It was published in the Jan/Feb 2019 issue of Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, won a Derringer Award a year later, and remains one of my favorites because I still remember how much fun I had writing it. (Over the years I've found that to be a fairly good litmus test for how well a story might do later, out there in the world.) Anyhow, the "teaser" I gave to Barb when she asked for one was "Two dimwitted criminals, a carjacking, a bank robbery, and an experimental self-driving getaway car. What could possibly go wrong?" What happens, of course, is that almost everything goes wrong. If you should read this crazy tale, I hope you'll like it.

But the title of my post today refers to my story that appeared in BCW this past week. It's called "High Noon in the Big Country"--Michael's "pick" for Issue #93 on June 11 (thanks, Michael)--and is sort of a mixed-bag Western/crime/fantasy story that's heavier on the horse-opera and paranormal genres than on the mystery genre. In this story, a guy named Eddie Johnson is on his way through Wyoming on horseback and happens onto a little cabin standing alone on the flats at the foot of a mountain range. The funny thing is, it's a place he recognizes even though he's never been there before. He even recognizes the lady who owns the cabin.

It is soon revealed that Eddie lives in the year 1989, and grew up going to movies every spare moment (can you spell "autobiographical"?). He especially loves Westerns. As a result of this lifelong cinematic obsession, he occasionally finds himself living, literally, in two alternating worlds. One is the present day--the late 20th Century--where he's on his way to South Dakota to play a small role (along with his horse) in a movie an old friend of his is filming there. The other world is set a hundred years ago, in the Old West. This double life of his scares him at times, but he's mostly grown accustomed to it. Anyhow, when he rides into the valley and sees the cabin, Eddie lapses into this other, long-ago world, and realizes this frontier lady is actually a character in a movie he has seen a dozen times, so he not only knows about her, he knows about her problem. She's worried about losing her homestead to a ruthless cattle baron who lives nearby. And while Eddie's not a brave gunfighter riding in to save the day, he does have a few things that might help the situation, like some items from the next century that he happens to be carrying with him on his trip.

The fun of this story, at least for me as I was writing it, was trying to blend the events of those two time periods into something that--like any Western--makes the good guys get what they deserve while the bad guys also get what they deserve. In our modern world of blurred lines, I think the old-time, clear-cut, white-hat-vs.-black-hat code of life and justice is one of the things I like most about Westerns. Bottom line is, this is probably one of the weirdest stories I've ever come up with, and I hope readers will enjoy it.

As I've said before, on Facebook and elsewhere, I owe sincere thanks to both Barb and Michael for allowing me to be a small part of Black Cat Weekly--both now and over the past couple of years. That magazine's a winner.

If you've seen issues of BCW, what do you think? Do you like the fact that it offers such a wide variety of stories? Any favorites so far? Have you had any of your own stories appear there? If you haven't seen or read an issue, I hope you will.

Meanwhile, stay cool--it's already hot as a two-dollar pistol down here--and keep writing and reading.

See you in two weeks.