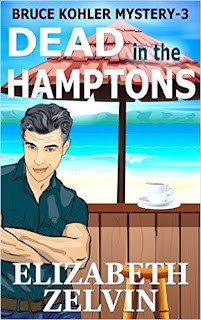

My guest this month is Ken Wishnia, co-editor with Chantelle Aimée Osman of

Jewish Noir II, just out from PM Press. The anthology has a foreword by Lawrence Block and a remarkable variety of Jewish voices and settings packed into twenty-three powerful stories, including my own contribution. Ken also edited the Anthony Award-nominated

Jewish Noir.

Kenneth Wishnia’s novels have been nominated for the Edgar, Anthony, and Macavity Awards. His short stories have appeared in EQMM, AHMM, Queens Noir, Long Island Noir, and elsewhere. He teaches writing, literature and other deviant forms of thought at Suffolk Community College on Long Island.

Secretary of State Madeleine Albright apparently didn’t learn that she was Jewish until 1996, more than 55 years after her parents sent her away from Czechoslovakia to the UK for safekeeping on the eve of WW II.

Cardinal John O’Connor, leader of the Catholic Church in New York City for 16 years, apparently died without ever learning that “his mother was born a Jew, the daughter of a rabbi” (see Cowan, Alison Leigh. “The Rabbi Cardinal O’Connor Never Knew: His Grandfather.”

New York Times, 10 June, 2014).

Even Eddie Muller, the “Czar of Noir” who was in the first Jewish Noir collection, told me that he had learned of some Jewish ancestry in his lineage. It turns out he was referring to his paternal grandfather--not exactly a distant relative--who changed his name from something very Jewish and foreign-sounding to make it easier to find a job when he emigrated to California a few generations back.

This raises some serious issues regarding the suppression of Jewish ethnicity during less enlightened times. I mean, how many Americans “discover” that they have Christian ancestors? People don’t discover they’re Christian, or part-Christian, because in the US that identity never needed to be suppressed or hidden.

But we’re writing about noir, aren’t we? Glad you asked!

|

Hedy Lamarr in

The Strange Woman (1946) |

As co-editor of

Jewish Noir II, naturally I’m a fan of film noir, and any such fan can tell you that one of the primary stylistic precursors to American film noir is German Expressionist film of the 1920s and early 1930s. Until recently, I had no idea how many of those influential practitioners of the art were German and Austrian Jews who would flee for Hollywood when Hitler came to power. This list includes: Fritz Lang, Billy Wilder, Otto Preminger, Edgar G. Ulmer and Fred Zinnemann (Austria); Robert Siodmak, Curtis Bernhardt, Max Ophuls and John Brahm (Germany); as well as Anatole Litvak (Ukraine).

Jewish directors who emigrated before 1933 include: Michael Curtiz (Hungary), Lewis Milestone, Charles Vidor and William Wyler (Germany); Hugo Haas (Czechoslovakia), and László Benedek (Hungary). (Note: I am indebted to Vincent Brook’s film study,

Driven to Darkness, for this information.)

|

Lauren Bacall & Humphrey Bogart in

Dark Passage (1947) |

I started to dig deeper, and learned that a large number of actors in film noir were also Jewish, almost always working under anglicized or completely invented names, a common practice in Hollywood till this day (I’m looking at you, Winona Ryder). The list includes: Lauren Bacall (b. Betty Joan Perske), Turhan Bey (b. Turhan Gilbert Selahattin Sahultavy), Lee J. Cobb (b. Leo Jacoby), Tony Curtis (b. Bernard Schwartz), Howard da Silva (b. Howard Silverblatt), Lee Grant (b. Lyova Haskell Rosenthal), Peter Lorre (b. Laszlo Lowenstein), Zero Mostel, Simone Signoret (b. Simone Kaminker), Sylvia Sydney (b. Sylvia Kosnow), Cornell Wilde (b. Kornél Lajos Weisz) and Shelley Winters (b. Shirley Schrift).

|

Cornell Wilde & Gene Tierney in

Leave Her to Heaven (1945) |

I compiled an appropriately obsessive list of Jewish directors, writers and actors who contributed significantly to the film noir canon; the list goes on for 14 pages in 10-point type.

Family note: My parents were both born in 1931, so of course they lived through the classic era in Hollywood. My dad was incredulous about Lee J. Cobb, asking, “Are you sure he was Jewish?” My mom’s response: “Cornell Wilde was Jewish?”

Crime writer S.J. Rozan’s response: “Fritz Lang was Jewish?” I know, his mother converted to Catholicism, mainly to avoid anti-Semitism in Germany, and Lang himself denied being Jewish for most of his life, but his mother was indeed Jewish, and converted when Lang was 10, meaning he was born Jewish. Under basic civil law and traditional Jewish law, Fritz Lang was Jewish.

|

| Simone Signoret in Diabolique (1955) |

Other Jewish (or part-Jewish) actors from the film noir era whose names might surprise you include: Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. (Doug Sr. b. Douglas Ullman), Leslie Howard (b. Leslie Howard Steiner), Paulette Goddard (b. Marion Goddard Levy), Paul Henreid (family name originally Hirsch), Hedy Lamarr (b. Hedvig Kiesler), and a real outlier: Ricardo Cortez (b. Jacob Krantz). Not sure why the ethnic masquerade of Latino identity, since in so many cases Jews masqueraded as Anglophone Christians.

Of course, many performers did this, regardless of their ethnicity (just ask Lucille LeSueur --I mean Joan Crawford). But why am I still finding out that so many key figures in world culture were Jewish? Just in the past couple of weeks, I’ve learned (from their obituaries!) that several prominent artists I had no idea were Jewish were in fact Jewish, including the British-born theatrical innovator Peter Brook (family name originally Bryk) and the composer of the James Bond theme, Monty Norman (b. Monty Noserovitch). I also just learned that Frank Oz, best known as the puppeteer for Miss Piggy, Bert, Grover and Yoda, was born Frank Oznowicz. And this happens all the time. Once again, people don’t hide their Christian identities. But Jews? That seems to be a case of, “Gee, mister, the name Issur Danielovitch Demsky doesn’t exactly spell box office gold on the marquee. How about we call you Kirk Douglas?”

|

Shelley Winters & Richard Conte

in Cry of the City (1948) |

This phenomenon, which still feels like a job requirement in certain professions, can also be turned against the Jews as an example of our allegedly uniquely perfidious nature: the poet T.S. Eliot appears to mock Jews who try to erase their ethnic identities when their crude manners (and propensity for evil) give them away every time, in his 1919 poem, “Sweeney among the Nightingales,” where the sixth stanza ends: “Rachel née Rabinovitch / Tears at the grapes with murderous paws.”

During Hollywood’s Red Scare, Representative John Rankin of Mississippi made a show of “outing” a number of prominent entertainers by revealing their birth names, implying that they were hiding their true identities in order to subvert American values from within, as if Danny Kaye (b. Dovid Daniel Kaminsky) and Eddie Cantor (b. Edward Isskowitz), two of Rankin’s examples, were planning to oppress American Christians by sneaking in communism between comedy routines, or something like that.

That’s one reason it was so much fun working on the Jewish Noir II anthology, in an era when we’re free to use our foreign-sounding, often polysyllabic names: Kirschman, Markowitz, Schneider, Sidransky, Zelvin and Vishnya (the Slavic pronunciation of Wishnia).

And speaking of my family name, it may be a liability on the bookstore shelves—I’m usually down on the floor with the rest of the W-Z authors--but it’s an asset in the world of Google searches: if you google “Kenneth Wishnia” you don’t get 100,000 other guys with the same name. You get me.

And by the way, I’m Jewish.