By Brian Thornton

(For my first post in this two-part series about the importance of giving your story a great beginning, please click here.)

Last time out I talked about the importance of a good opening for your novel. In the comments section folks quoted some great openers (Eve Fisher's quote of the opening line from Jane Austen's Pride & Prejudice comes to mind. Thanks Eve!)

In the interest of fostering further conversation, I've included a few of my own favorite novel openers, from across a broad spectrum of literature. If you find the opener intriguing, I can guarantee there is a strong payoff for your investment!

More on this in two weeks.

Read on:

"Nine months Landsman's been flopping at the Hotel Zamenhof without any of his fellow residents managing to get themselves murdered. Now somebody has put a bullet in the brain of the occupant of 208, a yid who was calling himself Emmanuel Lasker."

– The Yiddish Policeman's Union by Michael Chabon

"I know a place where there is no smog and no parking problem and no population explosion ... no Cold War and no H-bombs and no television commercials ... no Summit Conferences, no Foreign Aid, no hidden taxes-no income tax. The climate is the sort that Florida and California claim (and neither has), the land is lovely, the people are friendly and hospitable to strangers, the women are beautiful and amazingly anxious to please-"

– Glory Road by Robert A. Heinlein

"I first heard Personville called Poisonville by a red-haired mucker named Hickey Dewey in the Big Ship in Butte. He also called his shirt a shoit. I didn't think anything of what he had done to the city's name.Later I heard men who could manage their r's give it the same pronunciation. I still didn't see anything in it but the meaningless sort of humor that used to make richardsnary the thieves' word for the dictionary. A few years later I went to Personville and learned better."

– Red Harvest by Dashiell Hammett

"Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show. To begin my life with the beginning of my life, I record that I was born (as I have been informed and believe) on a Friday, at twelve o'clock at night. It was remarked that the clock began to strike, and I began to cry, simultaneously."

– David Copperfield by Charles Dickens

"I want the legs.'

"That was the first thing that came into my head. The legs were the legs of a twenty-year0old Vegas showgirl, a hundred feet long and with just enough curve and give and promise. Sure, there was no hiding the slightly worn hands or the beginning tugs of skin framing the bones in her face. But the legs, they lasted, I tell you. They endured. Two decades her junior, my skinny matchsticks were no comparison."

– Queenpin by Megan Abbott

"The trouble didn't seem to start so much as it simply landed, like a hunk of blazing debris."

– Dirt by Sean Doolittle

"In the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and the plain to the mountains. In the bed of the river there were pebbles and boulders, dry and white in the sun, and the water was clear and swiftly moving and blue in the channels. Troops went by the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the leaves of the trees. The trunks of the trees too were dusty and the leaves fell early that year and we saw the troops marching along the road and the dust rising and leaves, stirred by the breeze, falling and the soldiers marching and afterward the road bare and white except for the leaves."

– A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway

"At its northernmost limit, the California coastline suffered a winter of brutal winds pitched against iron-clad fog, and roiling seas whose whiplash could scar a man's cheek as quickly as a cat–o'–nine tails. Since the Gold Rush, mariners had run aground, and those who survived the splintering impact were often pulped when the tides tore them across the terrible strata of the volcanic landscape. For protection, the State had erected a score of lighthouses staffed with teams of three or four families who rotated duties that lasted into the day and into the night. The changing of the guard, as it were, was especially treacherous in some locations, such as Crescent City, accessible only by a tombolo that was flooded in high tide, or Point Bonita, whose wooden walkway, even after the mildest storm, tended to faint dead away from the loose soil of its mountaintop and tumble into the sea."

– Sunnyside by Glen David Gold

"In the shadows of the John F. Kennedy Expressway, surrounded by the warehouses, factories and auto-body shops, stands Villa d'Este, a family-run restaurant that serves generous portions of decidedly untrendy Italian-American food at reasonable prices. The restaurant was there more than thirty years before the expressway slashed the neighborhood in two and I imagine into me there long after the Kennedy collapses under the weight of bureaucratic neglect and political corruption. In Chicago, some things never go out of style."

– Big City, Bad Blood by Sean Chercover

"The heavy red-figured drapes over the courtroom windows were incompletely closed against the sun. Yellow daylight leaked in and dimmed the electric bulbs in the high ceiling. It picked out random details in the room: the glass water cooler standing against the paneled wall opposite the jury box, the court reporter's carmine-tipped fingers playing over her stenotype machine, Mrs. Perrine's experienced eyes watching me across the defense table."

– The Chill by Ross MacDonald

And that's it for this week. Make sure to tune in two weeks from now when I add a few more of examples and talk about what they do right to hook the reader. In the meantime feel free to weight in over in the comment section with examples of favorite opening lines and why they work for you!

See you in two weeks!

Brian

02 April 2015

01 April 2015

The Man Who Ate Babies: A Parable

This has nothing to do with April Fools' Day, by the way.

This has nothing to do with April Fools' Day, by the way. No babies were harmed in the making of this blog. I added the subtitle in hopes of not scaring off people who, like me, are squeamish about true crime. This parable was written by George Harvey, the editor of Harper's Weekly, and appeared in a March 1907 issue. I discovered it in the second volume of Mark Twain's autobiography and was struck by how relevant it seemed in light of certain events of recent years.

Oddly enough the question that most concerned Harvey seems to have been well settled, but the underlying issue is still very much with us. After the essay I will come back to explain the circumstances that led to Harvey's essay. The only editing I have done to the parable is to remove its introduction and split some paragraphs for ease of reading.

-Robert Lopresti

THE MAN WHO ATE BABIES

by George Harvey

Once there was a man who had the incomparable misfortune to be afflicted with a mania for eating babies. He was an extraordinary man, of astonishing vigor, of remarkable talents, of many engaging qualities, and of prodigious industry.

He had education and social position; he could earn plenty of money; and the diligent exercise of his intellectual gifts made him valuable to society. There was nothing within reasonable reach of a man of his profession which he could not have, but over what should have been a splendid career hung always the shadow of his remarkable propensity.

The precise dimensions and particulars of it were not definitely known to many persons. A few men who had a mania like his doubtless knew absolutely; a good many other men knew well enough; and there was practically a public property in the knowledge that he had, and gratified, cannibalistic inclinations of much greater intensity and more curious scope than those that commonly obtained among careless men.

There was an honest prejudice against him. Persons of considerable indulgence to eccentricities of deportment disliked to be in the same room with him. Sensitive stomachs instinctively rose against him. Yet he was tolerated, for, after all, nobody had ever seen him eat a baby.

One day another man—quite a worthless person—knocked him on the head, and let his pitiable spirit escape from its body. It made a great stir, for the man who was killed was very widely known, and his assailant was also notorious. There followed profuse discussion of the dead man’s character, qualities, and achievements. His record was assailed, but it was also warmly extenuated.

So the discussion went on, and waxed and waned as the months passed. But one day there was set up a great white screen, big enough for all the world to see, and over against it was placed a lantern that threw a light of wonderful intensity, and then came a person named Nemesis, with something under her arm, and took charge of the lantern. And then there fluttered forth all day on the great screen the moving picture of the poor monomaniac and a baby—how he found her, enticed her, cajoled her, and finally took her to his lair, prepared her for the table, and ate her up. Well; it was said that the picture was shocking, and that the public ought not to have been allowed to see it. Oh yes, it was shocking; never picture more so. But it was terribly well adapted to make it unpopular to eat babies.

Lopresti here again. In June 1906 the famous and celebrated architect Stanford White was shot to death by millionaire Harry K. Thaw. (These events were recalled in E.L. Doctorow's novel RAGTIME.) Thaw said he was driven to the crime by his obsession with White's earlier relationship with Evelyn Nesbit, a model Thaw had also had an affair with, and later married.

In court Nesbit reported that White had given her drugs and seduced her at age fifteen. Thaw was eventually found not guilty by reason of insanity. A few words from Twain's autobiography:

New York has known for years that the highly educated and elaborately accomplished Stanford Whtie was a shameless and pitiless wild beast disguised as a human being... He had a very hearty and breezy way with him, and he had the reputation of being limitlessly generous - toward men - and kindly, accommodating, and free-handed with his money -- toward men; but he was never charged with having in his composition a single rag of pity for an unfriended woman… [Congressman] Tom Reed said, "He ranks as a good fellow, but I feel the dank air of the charnel-house when he goes by."]

And here is how George Harvey introduced his parable in Harper's:

The President of the United States [Theodore Roosevelt] thinks that the papers that give "the full, disgusting particulars of the Thaw case" ought not to be admitted to the mails. Perhaps not. Perhaps the country at large does not need all the particulars, but in our judgment New York does need most of them, and it would be not a gain, but an injury, to morals if the newspapers were restrained from printing them.

We will try to explain.

Labels:

George Harvey,

Harry Thaw,

Lopresti,

Mark Twain,

murder,

parables,

Stanford White,

trials,

true crime

Location:

Bellingham, WA, USA

31 March 2015

Does Your City Cut It?

by Jim Winter

by Jim Winter

In the before time, in the long, long ago, I decided I would never write a story set in Los Angeles or New York. (I've since broken that rule with New York City.) No, I was going to be different. I was going to be unique. I was going to set my crime fiction in Cleveland.

OK, so Les Roberts had been doing it for about twelve years at that point. So his series was going to run out of steam soon. Right?

Er... No. He's still writing about Cleveland-based PI Milan Jackovich. But that's one series set on the North Coast. How many does New York have? Cleveland? Boston is lousy with crime fiction. Even Detroit, Cleveland's fellow declining Rust Belt city, has Loren Estleman and Elmore Leonard, and those are just the most notable Motor City authors.

Cleveland proved to be good fodder. My Cleveland is not Les's Cleveland is not Michael Koryta's. Cleveland. And that's pretty cool. Some have asked me why I haven't written in Cincinnati.

Well...

The city never really grabbed me the way Cleveland did. Ditto for Ohio's other big C, Columbus. I'm sure I could go nuts with Cincinnati, particularly with the West Side's well-defined culture that even they make fun of. I've taken stabs at it, but Cincinnati was always a place to live for me, not a place to tell stories. And I know that's not fair. Jonathan Valin spent the eighties writing about Harry Stoner's adventures in the Queen City.

So what is it that draws us to write about certain cities? LA and New York get a large share of stories simply because they are the two largest cities in the US. But what about the smaller cities? Why Cleveland for me and Les and Michael? What makes Stuart MacBride have his cops prowl the streets of Aberdeen, one of Scotland's lesser known cities, instead of, say, London or across the sea in Dublin?

A lot of it has to do with where the author is from. When we travel and pass through a city, we see a collection of tall buildings in the middle of urban sprawl. Every town has a McDonald's and carpet stores and the same gas station chains. I remember when one author came to Cincinnati for a signing, I suggested a place to eat simply because I liked eating there.

"Naw, that's a bit too chainy."

So it was. We hit the neighborhood bar across the parking lot from the bookstore. But these are the things that make cities interesting. Nick Kepler's favorite deli really exists on St. Clair. And while Milan Jackovich's Vuk's doesn't exist, it wasn't that long ago you could find two or three bars in Slavic Village similar to it.

As with fictional cities, it's that lived-in feel that makes even real-life cities come alive for the readers.

In the before time, in the long, long ago, I decided I would never write a story set in Los Angeles or New York. (I've since broken that rule with New York City.) No, I was going to be different. I was going to be unique. I was going to set my crime fiction in Cleveland.

OK, so Les Roberts had been doing it for about twelve years at that point. So his series was going to run out of steam soon. Right?

Er... No. He's still writing about Cleveland-based PI Milan Jackovich. But that's one series set on the North Coast. How many does New York have? Cleveland? Boston is lousy with crime fiction. Even Detroit, Cleveland's fellow declining Rust Belt city, has Loren Estleman and Elmore Leonard, and those are just the most notable Motor City authors.

Cleveland proved to be good fodder. My Cleveland is not Les's Cleveland is not Michael Koryta's. Cleveland. And that's pretty cool. Some have asked me why I haven't written in Cincinnati.

Well...

The city never really grabbed me the way Cleveland did. Ditto for Ohio's other big C, Columbus. I'm sure I could go nuts with Cincinnati, particularly with the West Side's well-defined culture that even they make fun of. I've taken stabs at it, but Cincinnati was always a place to live for me, not a place to tell stories. And I know that's not fair. Jonathan Valin spent the eighties writing about Harry Stoner's adventures in the Queen City.

So what is it that draws us to write about certain cities? LA and New York get a large share of stories simply because they are the two largest cities in the US. But what about the smaller cities? Why Cleveland for me and Les and Michael? What makes Stuart MacBride have his cops prowl the streets of Aberdeen, one of Scotland's lesser known cities, instead of, say, London or across the sea in Dublin?

A lot of it has to do with where the author is from. When we travel and pass through a city, we see a collection of tall buildings in the middle of urban sprawl. Every town has a McDonald's and carpet stores and the same gas station chains. I remember when one author came to Cincinnati for a signing, I suggested a place to eat simply because I liked eating there.

"Naw, that's a bit too chainy."

So it was. We hit the neighborhood bar across the parking lot from the bookstore. But these are the things that make cities interesting. Nick Kepler's favorite deli really exists on St. Clair. And while Milan Jackovich's Vuk's doesn't exist, it wasn't that long ago you could find two or three bars in Slavic Village similar to it.

As with fictional cities, it's that lived-in feel that makes even real-life cities come alive for the readers.

Location:

Cleveland, OH, USA

30 March 2015

My Father and Cousin Clyde

by Jan Grape

At the end of this article, you'll find a poem written by Bonnie Parker. Someone posted this poem on Facebook and it reminded me of my father, Thomas Lee Barrow. My father often told of how we were probably related to Clyde Barrow. I'm done a little bit of genealogy but never attempted to prove our connection to the notorious Mr, Clyde Barrow. It seemed more fun to just "say" we are related and leave it at that. But is it possible the criminal gene is what prompted me to write fictional crime stories? Who knows?

My father had a wonderful but, perhaps a bit strange, sense of humor and told stories of how he exploited the connection to Clyde Barrow. Let me explain, my father was born in Beaumont, TX in 1911 and was in his early twenties when Clyde and Bonnie were running around North Texas. Dad actually lived in Fort Worth, Texas then. A young man twenty-two or twenty-three in the early 1930s was like most young men of the day, prone to practical jokes.

Dad thought it was funny to walk into the First National Bank and write a counter check for ten or twenty dollars, sign his name, T. L, Barrow, walk over and hand the check to the teller. I know most of you would have trouble understanding but in those years, people didn't have scads of personal checks like we have nowadays. You mostly went to your bank, pick up a printed check form located at the bank's signature island table, wrote out the amount you wanted, gave it to a teller and got the amount you had asked for on the counter check.

Quite often the teller would look either scared or extra hard at my dad, sometimes nod to the bank manager, or ask for identification from my dad. They'd go ahead and give dad his ten or twenty dollars and breathe a sigh of relief that someone with the name of Barrow did nothing more than cash a check. The Fort Worth and Dallas newspapers had almost daily stories of the bad mob known as the Barrow gang. That name was familiar to everyone in the banking business.

A little more involved act of fun happened when two young men got together and took advantage of the Barrow name. Dad and his best friend, Ken Owens, used to go into bars and play their joke. Once inside the bar, my dad would walk down to the far end of the bar and sit on a stool there. His friend, Ken would park himself on a stool near the front door and get the bartender's attention. When the bar man walked up to him, Ken would say, "You see that man down there?" he'd nod towards my father, Tom Barrow. The barman would say "Yes."

Ken would then say, "That's Clyde Barrow's brother and he expects a free drink." The barman would nod and give a free drink to both my dad and Ken Owens. The two young men would drink their free drink and soon they'd leave, leaving the bartender wiping sweat off his brow, thankful that Clyde Barrow's brother had left his establishment. The two pranksters would then head down the street and around the corner to another bar and work it for another free drink.

Like I said earlier, I'm not totally sure of our connection to Clyde Barrow. I do know however, that my father, Thomas Lee Barrow, had a strong influence on my life. My love of mysteries because he gave me my first mystery paperbacks to read, Mike Hammer, Private Eye books written by Mickey Spillane, and Private Eye Shell Scott written by Richard Prather. I think, my mother and father were both quick with funny quips and they passed that gene along. I have a grandson, Riley Fox who lives in Portland, OR who is a stand-up comic. I don't have any bank robbing family members like Cousin Clyde and that's a good thing. I'd much rather write about mysteries and crime that to worry about a sheriff's posse or the FBI coming after me.

And although, Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow never had any children she definitely had a gift for writing poetry, and maybe that writing gene was passed to me through osmosis. Besides the poem listed here she wrote several poems which were published in the Dallas newspapers and there was a little notebook of her poems written while she was in jail.

I'll admit that I've always had a strong desire to claim a connection to Mr. Clyde Barrow. Wonder if I can get a free drink or two out of that?

My father had a wonderful but, perhaps a bit strange, sense of humor and told stories of how he exploited the connection to Clyde Barrow. Let me explain, my father was born in Beaumont, TX in 1911 and was in his early twenties when Clyde and Bonnie were running around North Texas. Dad actually lived in Fort Worth, Texas then. A young man twenty-two or twenty-three in the early 1930s was like most young men of the day, prone to practical jokes.

Dad thought it was funny to walk into the First National Bank and write a counter check for ten or twenty dollars, sign his name, T. L, Barrow, walk over and hand the check to the teller. I know most of you would have trouble understanding but in those years, people didn't have scads of personal checks like we have nowadays. You mostly went to your bank, pick up a printed check form located at the bank's signature island table, wrote out the amount you wanted, gave it to a teller and got the amount you had asked for on the counter check.

Quite often the teller would look either scared or extra hard at my dad, sometimes nod to the bank manager, or ask for identification from my dad. They'd go ahead and give dad his ten or twenty dollars and breathe a sigh of relief that someone with the name of Barrow did nothing more than cash a check. The Fort Worth and Dallas newspapers had almost daily stories of the bad mob known as the Barrow gang. That name was familiar to everyone in the banking business.

A little more involved act of fun happened when two young men got together and took advantage of the Barrow name. Dad and his best friend, Ken Owens, used to go into bars and play their joke. Once inside the bar, my dad would walk down to the far end of the bar and sit on a stool there. His friend, Ken would park himself on a stool near the front door and get the bartender's attention. When the bar man walked up to him, Ken would say, "You see that man down there?" he'd nod towards my father, Tom Barrow. The barman would say "Yes."

Ken would then say, "That's Clyde Barrow's brother and he expects a free drink." The barman would nod and give a free drink to both my dad and Ken Owens. The two young men would drink their free drink and soon they'd leave, leaving the bartender wiping sweat off his brow, thankful that Clyde Barrow's brother had left his establishment. The two pranksters would then head down the street and around the corner to another bar and work it for another free drink.

Like I said earlier, I'm not totally sure of our connection to Clyde Barrow. I do know however, that my father, Thomas Lee Barrow, had a strong influence on my life. My love of mysteries because he gave me my first mystery paperbacks to read, Mike Hammer, Private Eye books written by Mickey Spillane, and Private Eye Shell Scott written by Richard Prather. I think, my mother and father were both quick with funny quips and they passed that gene along. I have a grandson, Riley Fox who lives in Portland, OR who is a stand-up comic. I don't have any bank robbing family members like Cousin Clyde and that's a good thing. I'd much rather write about mysteries and crime that to worry about a sheriff's posse or the FBI coming after me.

And although, Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow never had any children she definitely had a gift for writing poetry, and maybe that writing gene was passed to me through osmosis. Besides the poem listed here she wrote several poems which were published in the Dallas newspapers and there was a little notebook of her poems written while she was in jail.

I'll admit that I've always had a strong desire to claim a connection to Mr. Clyde Barrow. Wonder if I can get a free drink or two out of that?

You've read the story of Jesse James of how he lived and died. If you're still in need; of something to read, here's the story of Bonnie and Clyde. Now Bonnie and Clyde are the Barrow gang I'm sure you all have read. how they rob and steal; and those who squeal, are usually found dying or dead. There's lots of untruths to these write-ups; they're not as ruthless as that. their nature is raw; they hate all the law, the stool pigeons, spotters and rats. They call them cold-blooded killers they say they are heartless and mean. But I say this with pride that I once knew Clyde, when he was honest and upright and clean. But the law fooled around; kept taking him down, and locking him up in a cell. Till he said to me; "I'll never be free, so I'll meet a few of them in hell" The road was so dimly lighted there were no highway signs to guide. But they made up their minds; if all roads were blind, they wouldn't give up till they died. If a policeman is killed in Dallas and they have no clue or guide. If they can't find a fiend, they just wipe their slate clean and hang it on Bonnie and Clyde. There's two crimes committed in America not accredited to the Barrow mob. They had no hand; in the kidnap demand, nor the Kansas City Depot job. If they try to act like citizens and rent them a nice little flat. About the third night; they're invited to fight, by a sub-gun's rat-tat-tat. They don't think they're too smart or desperate they know that the law always wins. They've been shot at before; but they do not ignore, that death is the wages of sin. Some day they'll go down together they'll bury them side by side. To few it'll be grief, to the law a relief but it's death for Bonnie and Clyde. |

Labels:

banks,

Bonnie and Clyde,

Bonnie Parker,

Clyde Barrow,

gangs,

Jan Grape,

robberies,

robbers

Location:

Cottonwood Shores, TX, USA

29 March 2015

Rejection

by Dale Andrews

Writers know that feeling. While all of us here at SleuthSayers love to write, and while each of us is published, very few of us have managed to carve out a profession from it. Certainly the days of O. Henry, when short stories alone could bring in enough to live on, are behind us. The market dwindles, the competition increases, and even a story lucky enough to get published only garners a few hundred dollars. Although writers of novels can still strike it rich, like actors a lot of them simply strike out. And continuing to swim against the current of repeated rejections can prove pretty tough.

How true is all of this? Let’s take a selective look at the record. William Golding’s Lord of the Flies was rejected 20 times before it was published. Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind collected 38 rejection letters. Anne Frank’s Diary of a Young Girl was rejected 15 times. Stephen King’s first novel, Carrie -- 30. Frank Herbert’s Dune -- 23. J.K. Rowling’s first work Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone -- 12 (initial printing was 500 copies). And Robert M. Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, collected an incredible 121 pre-publication rejections. When John le Carre submitted The Spy who Came in from the Cold he was advised that “it hasn't got any future.” Sanctuary by William Faulkner was deemed “unpublishable.” In response to his submission of Jungle Book Rudyard Kipling was advised to give up any writing ambitions since he clearly did not have the requisite command of the English language. And Agatha Christie, cherished in these environs and one of the best selling authors of all times, suffered four years of repeated rejections before her first mystery, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, found a willing publisher.

All of the foregoing examples are, of course, “success stories.” Perseverance won out. And the process, however grueling and depressing, in each case ended well with the publication of a well-received work; an “ahh-ha” to those earlier rejections.

But appreciate what the process is like not at the end, but in the middle, when the matter is still in doubt. Before each new submission the author invariably asks himself or herself, is my work really bad? Is it the publishing house that has missed the point, or is it me? And it is hard to answer those questions objectively, evaluating what one has subjectively created. Certainly editors and publishers are the keepers of the gate, the arbiters charged with the objective task of sorting wheat from chaff. But chaff still gets through, and sometimes wheat does not. Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, John Grisham’s A Time to Kill and Beatrix Potter’s The Tales of Peter Rabbit, to name but three, first reached the reading public only as a result of the authors’ exasperated decisions to self-publish.

So, how long should a writer persist in his or her advocacy in the face of the negative views of others? There can be no universal answer to that question since there is no prototypical rejected manuscript. But while the above examples are heartening, sometimes even ultimate success can be marred tragically by the disheartening submission process. There is probably no better example of this than the publication history of A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole.

Toole, by all accounts, was a brilliant professor of English at Hunter College in New York and at various Louisiana colleges. He completed A Confederacy of Dunces in 1963 after his discharge from the army. Dunces tells a picaresque tale of the travails of its hero Ignatius J. Reilly, an obese, self-styled intellectual who pursues employment while disdaining actual labor, lives with his mother, and constantly bemoans a horrific bus trip he once was forced to make to Baton Rouge. Toole submitted the manuscript to various publishing house, gaining some middling interest but absolutely no success. As an example, Simon and Schuster's rejection was premised on the articulated conclusion that Dunces was “essentially pointless.” Eventually, in the face of rejection, Toole gave up and basically withdrew from life, embracing a paranoiac view that the world was aligned against him. He lost his teaching positions and eventually, on March 26, 1969, at the age of thirty-one in Biloxi, Mississippi he inserted a hose through the window of his car, turned the vehicle on, settled comfortably into the front seat and waited peacefully until carbon monoxide took its course.

Toole had left the manuscript of Dunces on the top or the armoire in his bedroom in his mother’s house. Some years after his death his mother re-read the manuscript and decided that she would begin, again, the attempt to market it. Like Toole, she suffered through numerous rejections. Finally, with little left to lose, she undertook a crusade to persuade author Walker Percy, then a visiting professor at Tulane University, to review the manuscript. Her persistence led Percy initially to complain to family and friends about the apparently deranged woman who was stalking him peddling a manuscript. Eventually, in an act of desperation, Percy agreed to take a look. This is what he said in what eventually became his introduction to A Confederacy of Dunces:

[T]he lady was persistent, and it somehow came to pass that she stood in my office handing me the hefty manuscript. There was no getting out of it; only one hope remained—that I could read a few pages and that they would be bad enough for me, in good conscience, to read no farther. Usually I can do just that. Indeed the first paragraph often suffices. My only fear was that this one might not be bad enough, or might be just good enough, so that I would have to keep reading.

In this case I read on. And on. First with the sinking feeling that it was not bad enough to quit, then with a prickle of interest, then a growing excitement, and finally an incredulity: surely it was not possible that it was so good.

With the backing of Walker Percy A Confederacy of Dunces was finally published by LSU Press in 1980. In 1981 it won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.

So this ending is a happy one only in the most limited way. A Confederacy of Dunces found its publisher, its audience, and its accolades. But the rejection process that preceded all of this contributed to the untimely death of John Kennedy Toole. And as grim as this may be, well, at least Dunces eventually reached the reading public. Not so for many works that, good or bad, never find their own Walker Percy.

The Biographical Dictionary of Literary Failure, edited by C.D. Rose, is a compilation of 52 would-be writers whose work never saw the light of day nor the white of page. None of the authors ever got beyond rejection, but some “lost” works had even stranger back stories. Stanhope Barnes travels to London to discuss his novel Here Are the Young Men only to leave the only copy, never seen again, on an adjacent seat of the train. Veronica Vass, a cryptologist in England during World War II, wrote five novels in a devilish code, which she died without revealing, and which was never cracked. And perhaps saddest -- since it is a lesson on the folly, at times, of trying to overcome repeated rejections by relying too much upon the advice of others, is the case of Wendy Wedding, a budding minimalist who worked diligently editing what those who reviewed it described as a “huge” first draft of her novel The Empty Chair. Like many of us she was counseled to cut words. What happened? Here’s what C.D. Rose reports:

She removed every adjective from her book. Once that task was completed, she turned back to the beginning and started again. Relative clauses went next, then the passive voice. Metaphor, simile, symbol. All felt the knife. None were spared.

In an ending befitting of O.Henry, Wendy Wedding was ultimately left with one blank page.

Lessons to be learned? The Washington Post’s Michael Dirda, in his review of The Biographical Dictionary of Literary Failure (Washington Post, November 5, 2014), points us to Chekhov for guidance. Chekhov concluded that in judging the merits of literary works "[o]ne must be a god to be able to tell successes from failures without making a mistake."

28 March 2015

Never Marry a Crime Writer

(they let me off my leash again...)

Everybody knows they shouldn’t marry a writer. Mothers the world over have made that obvious: “For Gawd Sake, never marry a marauding barbarian, a sex pervert, or a writer.” (Or a politician, but that is my own personal bias. Ignore me.)

But for some reason, lots of innocent, unsuspecting people marry writers every year. Obviously, they don’t know about the (gasp!) “Zone.” (More obviously, they didn’t have the right mothers.)

Never mind: I’m here to help.

I think it pays to understand that writers aren’t normal humans: they write about people who don’t exist and things that never happened. Their brains work differently. They have different needs. And in some cases, they live on different planets (at least, my characters do, which is kind of the same thing.)

Thing is, writers are sensitive creatures. This can be attractive to some humans who think that they can ‘help’ poor writer-beings (in the way that one might rescue a stray dog.) True, we are easy to feed and grateful for attention. We respond well to praise. And we can be adorable. So there are many reasons you might wish to marry a writer, but here are 10 reasons why you shouldn’t:

The basics:

1. Writers are hoarders. Your house will be filled with books. And more books. It will be a shrine to books. The lost library of Alexandria will pale in comparison.

2. Writers are addicts. We mainline coffee. We’ve also been known to drink other beverages in copious quantities, especially when together with other writers in places called ‘bars.’

3. Writers are weird. Crime Writers are particularly weird (as weird as horror writers.) You will hear all sorts of gruesome research details at the dinner table. When your parents are there. Maybe even with your parents in mind.

4. Writers are deaf. We can’t hear you when we are in our offices, pounding away at keyboards. Even if you come in the room. Even if you yell in our ears.

5. Writers are single-minded. We think that spending perfectly good vacation money to go to crime writing conferences like Bouchercon is a really good idea. Especially if there are other writers there with whom to drink beverages.

The bad ones:

6. It may occasionally seem that we’d rather spend time with our characters than our family or friends. (See 9 below.)

7. We rarely sleep through the night. (It’s hard to sleep when you’re typing. Also, all that coffee...)

8. Our Google Search history is a thing of nightmares. (Don’t look. No really – don’t. And I’m not just talking about ways to avoid taxes… although if anyone knows a really fool-proof scheme, please email me.)

And the really bad ones:

9. If we could have affairs with our beloved protagonists, we probably would. (No! Did I say that out loud?)

10. We know at least twenty ways to kill you and not get caught.

RE that last one: If you are married to a writer, don’t worry over-much. Usually writers do not kill the hand that feeds them. Mostly, we are way too focused on figuring out ways to kill our agents, editors, and particularly, reviewers.

Melodie Campbell writes funny books, like The Artful Goddaughter, book 3 in the award-winning series about a reluctant mob goddaughter. Please don't be reluctant to check them out.

Everybody knows they shouldn’t marry a writer. Mothers the world over have made that obvious: “For Gawd Sake, never marry a marauding barbarian, a sex pervert, or a writer.” (Or a politician, but that is my own personal bias. Ignore me.)

But for some reason, lots of innocent, unsuspecting people marry writers every year. Obviously, they don’t know about the (gasp!) “Zone.” (More obviously, they didn’t have the right mothers.)

Never mind: I’m here to help.

I think it pays to understand that writers aren’t normal humans: they write about people who don’t exist and things that never happened. Their brains work differently. They have different needs. And in some cases, they live on different planets (at least, my characters do, which is kind of the same thing.)

Thing is, writers are sensitive creatures. This can be attractive to some humans who think that they can ‘help’ poor writer-beings (in the way that one might rescue a stray dog.) True, we are easy to feed and grateful for attention. We respond well to praise. And we can be adorable. So there are many reasons you might wish to marry a writer, but here are 10 reasons why you shouldn’t:

The basics:

1. Writers are hoarders. Your house will be filled with books. And more books. It will be a shrine to books. The lost library of Alexandria will pale in comparison.

2. Writers are addicts. We mainline coffee. We’ve also been known to drink other beverages in copious quantities, especially when together with other writers in places called ‘bars.’

3. Writers are weird. Crime Writers are particularly weird (as weird as horror writers.) You will hear all sorts of gruesome research details at the dinner table. When your parents are there. Maybe even with your parents in mind.

4. Writers are deaf. We can’t hear you when we are in our offices, pounding away at keyboards. Even if you come in the room. Even if you yell in our ears.

5. Writers are single-minded. We think that spending perfectly good vacation money to go to crime writing conferences like Bouchercon is a really good idea. Especially if there are other writers there with whom to drink beverages.

The bad ones:

6. It may occasionally seem that we’d rather spend time with our characters than our family or friends. (See 9 below.)

7. We rarely sleep through the night. (It’s hard to sleep when you’re typing. Also, all that coffee...)

8. Our Google Search history is a thing of nightmares. (Don’t look. No really – don’t. And I’m not just talking about ways to avoid taxes… although if anyone knows a really fool-proof scheme, please email me.)

And the really bad ones:

9. If we could have affairs with our beloved protagonists, we probably would. (No! Did I say that out loud?)

10. We know at least twenty ways to kill you and not get caught.

RE that last one: If you are married to a writer, don’t worry over-much. Usually writers do not kill the hand that feeds them. Mostly, we are way too focused on figuring out ways to kill our agents, editors, and particularly, reviewers.

Melodie Campbell writes funny books, like The Artful Goddaughter, book 3 in the award-winning series about a reluctant mob goddaughter. Please don't be reluctant to check them out.

27 March 2015

You Asked For It (or: Changing Men's Minds Redux)

by Dixon Hill

By Dixon Hill

Not long ago, I posted an article linked to a story discussing the difficulties encountered by female police officers in Afghanistan. At that time, I told you about one of my experiences concerning the education of foreign officers where females soldiers were concerned.

I also mentioned that I'd had a second experience educating foreign troops to change their view of women, and some readers asked me to post this experience, so that's what you'll be reading below.

I think I should point out that there are different ways of helping chauvinistic men see "the weaker

sex" in a stronger light. Some of you may not approve of my particular methods in this case, but I hope you'll realize that my objective was to help soldiers in an army that was preparing to send troops into trouble spots for the United Nations, as well as other peace keeping organizations, avoid potential problems.

And, the biggest problem here was that we didn't want some unit subordinate to the UN, for instance, to commit war crimes.

And, the biggest problem here was that we didn't want some unit subordinate to the UN, for instance, to commit war crimes.

Our concern was, because of these troops' cultural views on the roles played by men and women during armed conflict, they might ignorantly be led to shooting innocent people during a fire fight.

I'm not talking about "collateral damage" here: I'm talking about troops intentionally shooting innocent people, because they might hold the view that the gender of these folks made them legal targets on the battlefield.

The following is what happened:

My A-Team was working in a foreign country, running a leadership school for them, and the Host Nation held a demonstration of their military prowess (as is common when an A-Team visits). During this demo, they showed us the method they used to determine if a person was an enemy combatant or not.

During the demo, they conducted a live-fire exercise against targets with full-color illustrated paper figures taped on the front, which were somewhat similar to the targets in the montage on the left.

Some of these target figures were men or boys. Some were women or girls. And many held fire arms or knives, while others carried groceries, a camera or some other innocuous item.

I was quite used to these targets, having used them myself when in various schools, or other training, to learn selective shooting techniques. And, I knew that the trick to succeeding against an array of these targets -- erected by someone who was trying to trick you into shooting "innocent" targets, in order to train you NOT to do so in the future -- was to concentrate on the target's hands.

If the target holds a weapon, you shoot it. If not, you can't, because that person (unless identified by uniform or in some other manner) is a non-combatant; so hold your fire.

The soldiers in this Host Nation, however, had a different practice.

Their procedure?

"If it's male -- KILL IT! If it's female, let it live."

They didn't care that they shot men holding little boy's hands. They shot the little boys too!

(I was stupefied.)

If the man was holding a little girl's hand, however, the girl was not to be shot. Just the man beside her.

So, too, did the female wielding a shotgun go without injury. But, the man holding groceries (his target standing beside the shotgun-wielding female) was filled with holes.

It was unbelievable. But it happened.

That evening, in our team hooch, my Team Leader (a captain rather new to SF) looked at me and said, "Sergeant Hill, you're scheduled to teach the class about the Law of Land Warfare. Your class has to address this issue! These guys are in an army that's getting ready to do a lot of work for the U.N., and other international peace keeping organizations, and they're going to get into firefights going where they're going. You've got to make it clear that they can't kill innocent civilians: they're going to wind up committing war crimes if you don't."

So, this is how I wound up teaching a class, in which I used a rather oddly chosen movie to carefully outline what made a person a "combatant" under the Law of Land Warfare. And, I carefully explained that women could be combatants. And that NOT ALL men were combatants. And that they'd better be sure they weren't shooting innocent civilians, or they could be hung for committing a war crime.

Problem was: These guys weren't paying any more attention than those Middle-Eastern officers had paid to that female Spec-4 I mentioned in that previous post. Their culture told them that all men were legal targets, and all women were innocent. They didn't know why I was confused about this, but clearly I was.

I hated to spoil their dream of all women being innocent, but . . .

Well, I'd prepared for this moment.

And now I decided it was time for a little shock treatment. About a half-hour before class, I had put a TV set in the class room (which was outdoors; I had to run two 100-foot extension cords), along with a VCR. I had the tape of Apocalypse Now all loaded, and had run it up to the point where the Air Cavalry attacks the Viet Cong village in a helicopter assault. It was dark out, being night time.

So, I shut off the lights, and hit PLAY.

I had pre-set the tape so that we started right in the middle of the battle: VC anti-aircraft batteries firing at the choppers, choppers machine-gunning rifle-wielding VC and firing rockets into the anti-aircraft sites. The students leaned forward, excited.

I stood back and used a pointer, tapping it on the TV screen, pointing to the weapons certain VC characters carried, saying: "Weapon! Combatant! -- LEGAL TARGET!" each time. Or, I might point out "Uniform! Combatant! LEGAL TARGET!"

I stood back and used a pointer, tapping it on the TV screen, pointing to the weapons certain VC characters carried, saying: "Weapon! Combatant! -- LEGAL TARGET!" each time. Or, I might point out "Uniform! Combatant! LEGAL TARGET!"

My pointer tapped the anti-aircraft crew gathered around their weapon: "Combatants, or not?" I bellowed above the movie soundtrack.

"Combatants, sir!" came the mass reply. This went on for some time.

Then . . .

we came to the scene where the Viet Cong female throws a conical hat into the helicopter parked on the ground. The chopper explodes, because her hat hid a grenade. The students cried out, shocked.

A second or two later, I tapped the end of my pointer against the woman's running figure as she scrambled across the screen, away from the carnage.

"Combatant, or not?" I called.

They stared at me, silent, blinking, heads swiveling between me, my pointer and the figure on the screen.

"COMBATANT OR NOT?" I demanded.

Before I could get an answer, she was gunned down from a helicopter above.

My students gasped. They clasped their hands over their mouths. Some of them rocked back and forth in horror and confusion, where they sat on the split-log benches. Their horror was nearly palpable.

So was their confusion.

And, frankly, this was the moment I'd been waiting for.

I froze the picture on the image of the man who had used the machine gun to shoot down that woman. (I think it was Robert Duvall, as LTC Kilgore, but I can't find a copy of this particular scene online for some reason.) Slapping my pointer on his image, I snapped, "Is this man going to be tried and hung by an international court of law for war crimes? Or is he safe from such charges? Was that woman he killed a combatant, or not? If she was a combatant, he's safe. If she wasn't --- He . . . will . . . be . . . HANGED!"

Not an eye in that classroom wandered for the next two hours, until my class was over. For many days afterward, students would quietly approach other members of my A-Team, suggesting scenarios and asking if so-and-so would be a combatant or not. From what I heard, many of these questions centered around actions performed by women during combat. As one of my team members said to me: "What the hell did you tell these guys? They're all scared s--tless of being hung for war crimes, or else being shot by some chick!"

I nodded and smiled. "Good!"

See you in two weeks,

--Dixon

Not long ago, I posted an article linked to a story discussing the difficulties encountered by female police officers in Afghanistan. At that time, I told you about one of my experiences concerning the education of foreign officers where females soldiers were concerned.

I also mentioned that I'd had a second experience educating foreign troops to change their view of women, and some readers asked me to post this experience, so that's what you'll be reading below.

I think I should point out that there are different ways of helping chauvinistic men see "the weaker

sex" in a stronger light. Some of you may not approve of my particular methods in this case, but I hope you'll realize that my objective was to help soldiers in an army that was preparing to send troops into trouble spots for the United Nations, as well as other peace keeping organizations, avoid potential problems.

And, the biggest problem here was that we didn't want some unit subordinate to the UN, for instance, to commit war crimes.

And, the biggest problem here was that we didn't want some unit subordinate to the UN, for instance, to commit war crimes. Our concern was, because of these troops' cultural views on the roles played by men and women during armed conflict, they might ignorantly be led to shooting innocent people during a fire fight.

I'm not talking about "collateral damage" here: I'm talking about troops intentionally shooting innocent people, because they might hold the view that the gender of these folks made them legal targets on the battlefield.

The following is what happened:

My A-Team was working in a foreign country, running a leadership school for them, and the Host Nation held a demonstration of their military prowess (as is common when an A-Team visits). During this demo, they showed us the method they used to determine if a person was an enemy combatant or not.

During the demo, they conducted a live-fire exercise against targets with full-color illustrated paper figures taped on the front, which were somewhat similar to the targets in the montage on the left.

|

| In the montage left, above, this woman is a victim. In another target version, she is carrying groceries. Here, she is clearly a COMBATANT, pointing a gun at you. |

|

| In other versions, this guy is carrying a movie camera. |

I was quite used to these targets, having used them myself when in various schools, or other training, to learn selective shooting techniques. And, I knew that the trick to succeeding against an array of these targets -- erected by someone who was trying to trick you into shooting "innocent" targets, in order to train you NOT to do so in the future -- was to concentrate on the target's hands.

If the target holds a weapon, you shoot it. If not, you can't, because that person (unless identified by uniform or in some other manner) is a non-combatant; so hold your fire.

The soldiers in this Host Nation, however, had a different practice.

Their procedure?

"If it's male -- KILL IT! If it's female, let it live."

They didn't care that they shot men holding little boy's hands. They shot the little boys too!

(I was stupefied.)

If the man was holding a little girl's hand, however, the girl was not to be shot. Just the man beside her.

So, too, did the female wielding a shotgun go without injury. But, the man holding groceries (his target standing beside the shotgun-wielding female) was filled with holes.

It was unbelievable. But it happened.

That evening, in our team hooch, my Team Leader (a captain rather new to SF) looked at me and said, "Sergeant Hill, you're scheduled to teach the class about the Law of Land Warfare. Your class has to address this issue! These guys are in an army that's getting ready to do a lot of work for the U.N., and other international peace keeping organizations, and they're going to get into firefights going where they're going. You've got to make it clear that they can't kill innocent civilians: they're going to wind up committing war crimes if you don't."

So, this is how I wound up teaching a class, in which I used a rather oddly chosen movie to carefully outline what made a person a "combatant" under the Law of Land Warfare. And, I carefully explained that women could be combatants. And that NOT ALL men were combatants. And that they'd better be sure they weren't shooting innocent civilians, or they could be hung for committing a war crime.

Problem was: These guys weren't paying any more attention than those Middle-Eastern officers had paid to that female Spec-4 I mentioned in that previous post. Their culture told them that all men were legal targets, and all women were innocent. They didn't know why I was confused about this, but clearly I was.

I hated to spoil their dream of all women being innocent, but . . .

Well, I'd prepared for this moment.

And now I decided it was time for a little shock treatment. About a half-hour before class, I had put a TV set in the class room (which was outdoors; I had to run two 100-foot extension cords), along with a VCR. I had the tape of Apocalypse Now all loaded, and had run it up to the point where the Air Cavalry attacks the Viet Cong village in a helicopter assault. It was dark out, being night time.

So, I shut off the lights, and hit PLAY.

I had pre-set the tape so that we started right in the middle of the battle: VC anti-aircraft batteries firing at the choppers, choppers machine-gunning rifle-wielding VC and firing rockets into the anti-aircraft sites. The students leaned forward, excited.

I stood back and used a pointer, tapping it on the TV screen, pointing to the weapons certain VC characters carried, saying: "Weapon! Combatant! -- LEGAL TARGET!" each time. Or, I might point out "Uniform! Combatant! LEGAL TARGET!"

I stood back and used a pointer, tapping it on the TV screen, pointing to the weapons certain VC characters carried, saying: "Weapon! Combatant! -- LEGAL TARGET!" each time. Or, I might point out "Uniform! Combatant! LEGAL TARGET!"My pointer tapped the anti-aircraft crew gathered around their weapon: "Combatants, or not?" I bellowed above the movie soundtrack.

"Combatants, sir!" came the mass reply. This went on for some time.

Then . . .

we came to the scene where the Viet Cong female throws a conical hat into the helicopter parked on the ground. The chopper explodes, because her hat hid a grenade. The students cried out, shocked.

A second or two later, I tapped the end of my pointer against the woman's running figure as she scrambled across the screen, away from the carnage.

"Combatant, or not?" I called.

They stared at me, silent, blinking, heads swiveling between me, my pointer and the figure on the screen.

"COMBATANT OR NOT?" I demanded.

Before I could get an answer, she was gunned down from a helicopter above.

My students gasped. They clasped their hands over their mouths. Some of them rocked back and forth in horror and confusion, where they sat on the split-log benches. Their horror was nearly palpable.

So was their confusion.

And, frankly, this was the moment I'd been waiting for.

I froze the picture on the image of the man who had used the machine gun to shoot down that woman. (I think it was Robert Duvall, as LTC Kilgore, but I can't find a copy of this particular scene online for some reason.) Slapping my pointer on his image, I snapped, "Is this man going to be tried and hung by an international court of law for war crimes? Or is he safe from such charges? Was that woman he killed a combatant, or not? If she was a combatant, he's safe. If she wasn't --- He . . . will . . . be . . . HANGED!"

Not an eye in that classroom wandered for the next two hours, until my class was over. For many days afterward, students would quietly approach other members of my A-Team, suggesting scenarios and asking if so-and-so would be a combatant or not. From what I heard, many of these questions centered around actions performed by women during combat. As one of my team members said to me: "What the hell did you tell these guys? They're all scared s--tless of being hung for war crimes, or else being shot by some chick!"

I nodded and smiled. "Good!"

See you in two weeks,

--Dixon

26 March 2015

A Little Religious Conspiracy Theory

by Eve Fisher

As you hopefully know by now, I love a good conspiracy theory. And some events generate lots of them. A very early event that has not yet stopped generating conspiracy theories is, of course, the death of Jesus, and since Palm Sunday is the 29th and Easter comes next, I thought it would be a good time to review some of most interesting conspiracy theories. If nothing else, just to prove that it's not just politics that brings out the crazy...

(1) That Jesus would be replaced by his twin, or doppelganger, who would die on the cross for him so that he could appear to be resurrected and, thus, start a whole new religion. Or get out of town later. Both ideas have been used. The most likely candidate? Thomas, who was known as "the Twin" (Didymas), which certainly puts a whole new spin on Doubting Thomas, doesn't it?

(2) Another theory says that these 2 messages - the colt and the guy with the pitcher of water - were coded messages, letting the conspirators know that the time was at hand for a major magic act to take place. This conspiracy theory breaks down a couple of ways:

Coming soon — who killed Chaucer?

First of all, there were at least three real conspiracies that surrounded Jesus:

- The first one in (among other places) Matthew 26:14-16, where the chief priests paid Judas to betray Jesus so they could have him executed, quickly and relatively quietly, before the Passover.

- The second, of course, was the show trial before first Caiaphas and then Pilate, complete with manufactured witnesses and a lot of fake weeping, wailing and tearing of clothes in horror.

- The third in Matthew 28:11-15, after the finding of the empty tomb: "Now while they [the disciples] were going, some of the guard went into the city and told the chief priests everything that had happened. After the priests had assembled with the elders, they devised a plan to give a large sum of money to the soldiers, telling them, “You must say, ‘His disciples came by night and stole him away while we were asleep.’ If this comes to the governor’s ears, we will satisfy him and keep you out of trouble.” So they took the money and did as they were directed. And this story is still told among the Jews to this day."

- BTW that "keep you out of trouble" part was VERY important, because Roman guards who lost prisoners were killed in their stead.

"When they were approaching Jerusalem, at Bethphage & Bethany, near the Mount of Olives, he sent 2 of his disciples & said to them, “Go into the village ahead of you, & immediately as you enter it, you will find tied there a colt that has never been ridden; untie it & bring it. If anyone says to you, ‘Why are you doing this?’ just say this, ‘The Lord needs it and will send it back here immediately.’” They went away & found a colt tied near a door, outside in the street. As they were untying it, some of the bystanders said to them, “What are you doing, untying the colt?” They told them what Jesus had said; & they allowed them to take it. Mark l1:1-6

Then came the day of Unleavened Bread, on which the Passover lamb had to be sacrificed. So Jesus sent Peter and John, saying, “Go and prepare the Passover meal for us that we may eat it.” They asked him, “Where do you want us to make preparations for it?” “Listen,” he said to them, “when you have entered the city, a man carrying a jar of water will meet you; follow him into the house he enters and say to the owner of the house, ‘The teacher asks you, “Where is the guest room, where I may eat the Passover with my disciples?”’ He will show you a large room upstairs, already furnished. Make preparations for us there.” So they went and found everything as he had told them; and they prepared the Passover meal. Luke 22:7-13The above two passages have been used repeatedly to prove that there was a plot, a conspiracy, and Jesus was in on it and/or was the mastermind. But what kind of plot? What kind of conspiracy? Folks, there are a lot of them:

(1) That Jesus would be replaced by his twin, or doppelganger, who would die on the cross for him so that he could appear to be resurrected and, thus, start a whole new religion. Or get out of town later. Both ideas have been used. The most likely candidate? Thomas, who was known as "the Twin" (Didymas), which certainly puts a whole new spin on Doubting Thomas, doesn't it?

(2) Another theory says that these 2 messages - the colt and the guy with the pitcher of water - were coded messages, letting the conspirators know that the time was at hand for a major magic act to take place. This conspiracy theory breaks down a couple of ways:

- One version says that the plan was for Jesus to be arrested, tried, convicted, crucified and drugged with that vinegar on a stick (John 19:28). He was then taken down - comatose but still alive - nursed back to health, appeared to the disciples, who spread the story of his resurrection while he went off to Tibet to become a monk in the Himalayas.

- Another version was given in the 1960's book "The Passover Plot", where they said that everything was going according to the above plan BUT then came some stupid soldier with a spear. For some reason, he hadn't been bribed, and he killed a living Jesus on the cross by mistake. And then the disciples had to make up a story and stick to it. Hence, John 19 & 20, Luke 23 & 24, etc.

- Dorothy Sayers in her "The Man Born to be King" says that it was a code, a conspiracy, but it was set up by the Zealots: they offered Jesus a choice between a horse and a colt, and if he took the horse, they'd follow him in an uprising against Rome. If he took the colt, he was on his own. They'd find another leader. He took the colt, and death was the result. BUT Judas didn't know the details, and he thought that by taking the colt, Jesus had turned political, and so Judas turned him in for being less holy than Judas wanted/needed him to be. Actually, I kind of like this one - at least it makes sense in the political climate of the time, and it gives Judas a reason to betray Jesus.

- D. M. Murdock, in her book "The Christ Conspiracy: The Greatest Story Ever Sold," says that Christianity was invented by a variety of secret societies and mystery religions to unify the Roman Empire under one state religion. Without, of course, bothering to figure out WHY the Roman Empire needed one state religion and ignoring the fact that it already had a form of it in Rome's ready worship of any new god that came along, not to mention the Emperor Cultus... Let's just say that this is the kind of book that makes historians like me go bang their head against a wall over and over again...

- Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and the Holy Grail - ad infinitum, ad nauseum…

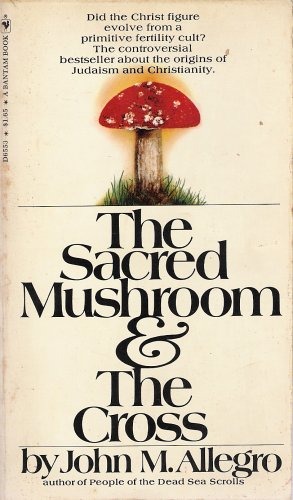

- My personal favorite of all conspiracy theories is in an obscure book from the 1970's, "The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross" by John Marco Allegro. According to Allegro, Jesus was actually a psychedelic mushroom. Or hallucinations resulting from taking psychedelic mushrooms. And, in case you're wondering, yes, I absolutely do believe that psychedelic mushrooms were indeed consumed in the conception and writing of that book…

Coming soon — who killed Chaucer?

Labels:

Christ,

conspiracies,

conspiracy theories,

Jesus,

Nazareth,

plots,

religions,

show trials

25 March 2015

Dead Zero

I came to Steve Hunter somewhere in mid-career - I mean his - when I read HOT SPRINGS, which came out in 2000. The next book I read was DIRTY WHITE BOYS, which had been released in 1994. Then, like a lot of us do, I went back and started at the beginning, with THE MASTER SNIPER, from 1980, and read the rest of his novels in order. Although some of them are stand-alones, most of them focus on a Marine sniper, Bob Lee Swagger, who saw combat in Viet Nam, and his dad, Earl, a Medal of Honor winner in the Pacific war. And the books cross-pollinate, in the sense that some members of the cast have running cameos.

My own personal favorite in BLACK LIGHT, and when I suggested to Hunter in an e-mail exchange that I guessed his own favorite was TIME TO HUNT, he admitted it was true. My reasons for liking BLACK LIGHT are its nimbleness and canny plotting, and I think Steve's reasons for liking TIME TO HUNT are about emotional resonance.

I have to say that a couple of the recent Bob Lee books left me somewhat lukewarm. DEAD ZERO and SOFT TARGET let a little too much of Hunter's politics leak in. I could say the same of John LeCarre, in all fairness. Hunter's somewhere off to my Right, and LeCarre more to my Left. (I found ABSOLUTE FRIENDS enormously irritating.) Samuel Goldwyn is supposed to have once said, "If you want to send a message, use Western Union."

Mind you, I love the gun stuff in Hunter's books. I got no issue with it. But everybody doesn't feel the same way. He tells a story where somebody said to him, Gee, they liked the books, but they got bogged down in the guncraft, and couldn't there be less of it? Which reminds me of a Tony Hillerman anecdote. When he pitched the first of his Navajo mysteries, THE BLESSING WAY, one agent came back and told him, This is pretty good, but can you get rid of all that Indian crap? I guess you have to take the bitter with the sweet.

Which brings us to SNIPER'S HONOR, out this past year.

Two linked plot lines. The first is the Ostfront in 1944, a Russian sharpshooter, Mili Petrova, and the second is Bob Lee in present day, trying to figure out how come her story had been erased from the historical record. And of course the stories collide. I happen to really like the device of shifting POV, with the past impinging on the present, not least because I've used it myself. (The bounty hunter novella DOUBTFUL CANYON has two interdependent narratives, told fifty years apart.) In the case of SNIPER'S HONOR, the game's afoot in Ukraine, and Mili and Bob Lee traverse the same terrain, with both similar and competing obstacles in their path. Mili setting up a thousand-yard cold-bore shot on a particularly loathsome Obergruppenfuhrer-SS - think Reinhard Heydrich - and Bob Lee tracking her from a distance in time, but seeing her boots on the ground in his mind's eye.

This is some trick, too, and what you might call a lap dissolve, in movie terms, where you see the landscape mapped out, with a sniper's eye (or rather, two sets of snipers' eyes), and how their parallel approach to the target intersects. The suspense is killing me. Does she make the shot? You know better than to ask. You'll find out on p. 327, point of aim, range, trajectory, bullet weight, deflection - let's just say a few variables.

What you really want to know is, though, is the Master Sniper back on game? I'm here to bear witness. There's a boatload of gun stuff, sure. I ate it up. There's one hell of a good story, too, at both ends. And there's just deserts. (I checked the spelling on that.) Is there anything more you need? Well, the next book, I, RIPPER, is out this coming May. Knife work, I'm thinking. Gaslight. Cobblestoned streets, greasy with damp. Arterial spray. I can't hardly wait.

My own personal favorite in BLACK LIGHT, and when I suggested to Hunter in an e-mail exchange that I guessed his own favorite was TIME TO HUNT, he admitted it was true. My reasons for liking BLACK LIGHT are its nimbleness and canny plotting, and I think Steve's reasons for liking TIME TO HUNT are about emotional resonance.

I have to say that a couple of the recent Bob Lee books left me somewhat lukewarm. DEAD ZERO and SOFT TARGET let a little too much of Hunter's politics leak in. I could say the same of John LeCarre, in all fairness. Hunter's somewhere off to my Right, and LeCarre more to my Left. (I found ABSOLUTE FRIENDS enormously irritating.) Samuel Goldwyn is supposed to have once said, "If you want to send a message, use Western Union."

Mind you, I love the gun stuff in Hunter's books. I got no issue with it. But everybody doesn't feel the same way. He tells a story where somebody said to him, Gee, they liked the books, but they got bogged down in the guncraft, and couldn't there be less of it? Which reminds me of a Tony Hillerman anecdote. When he pitched the first of his Navajo mysteries, THE BLESSING WAY, one agent came back and told him, This is pretty good, but can you get rid of all that Indian crap? I guess you have to take the bitter with the sweet.

Which brings us to SNIPER'S HONOR, out this past year.

Two linked plot lines. The first is the Ostfront in 1944, a Russian sharpshooter, Mili Petrova, and the second is Bob Lee in present day, trying to figure out how come her story had been erased from the historical record. And of course the stories collide. I happen to really like the device of shifting POV, with the past impinging on the present, not least because I've used it myself. (The bounty hunter novella DOUBTFUL CANYON has two interdependent narratives, told fifty years apart.) In the case of SNIPER'S HONOR, the game's afoot in Ukraine, and Mili and Bob Lee traverse the same terrain, with both similar and competing obstacles in their path. Mili setting up a thousand-yard cold-bore shot on a particularly loathsome Obergruppenfuhrer-SS - think Reinhard Heydrich - and Bob Lee tracking her from a distance in time, but seeing her boots on the ground in his mind's eye.

This is some trick, too, and what you might call a lap dissolve, in movie terms, where you see the landscape mapped out, with a sniper's eye (or rather, two sets of snipers' eyes), and how their parallel approach to the target intersects. The suspense is killing me. Does she make the shot? You know better than to ask. You'll find out on p. 327, point of aim, range, trajectory, bullet weight, deflection - let's just say a few variables.

What you really want to know is, though, is the Master Sniper back on game? I'm here to bear witness. There's a boatload of gun stuff, sure. I ate it up. There's one hell of a good story, too, at both ends. And there's just deserts. (I checked the spelling on that.) Is there anything more you need? Well, the next book, I, RIPPER, is out this coming May. Knife work, I'm thinking. Gaslight. Cobblestoned streets, greasy with damp. Arterial spray. I can't hardly wait.

24 March 2015

The Battle Of A Thousand Slain

by David Dean

I would venture to guess that one of the least known periods in American history lies between the years of the Revolutionary War and the Civil War. Many of us are pretty well versed in the events leading to the creation of the United States, and that later titanic struggle to keep them united, but what lies between them is often murky, if not completely unknown. For instance, how many folks do you know who can tell you anything coherent about the War of 1812 or the Mexican-American War? Not many, I bet. It seems to be a rather obscure period to most people, almost as if we, as a nation, had yet to gel, to come completely into focus. And maybe there's some truth in that. If you are wondering to what literary purpose this line of thought could possibly lead, I can only offer this historical terra incognita as potentially fertile ground for the writer's imagination. The following is a brief account of one event during this period with which you may not be acquainted. If you are, I salute you, if not, read on.

In the year 1791, the brand new nation of the United States, still recovering from years of protracted warfare with England, faced one of its greatest challenges--the Northwest Frontier. Not the northwest that now encompasses Idaho, Oregon and Rob Lopresti's beloved Washington State, but a great swath of territory bounded by the Ohio River to the east and south, the Mississippi to the west, with Canada as its northern border. An area that now includes the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Kentucky, West Virginia, and part of Pennsylvania. This was Indian Country. Of course, it had always been Indian country, but in the years leading up to 1791, it had become more so due to the pressure of westward expansion by the new Americans. Many tribes that had once lived in New Jersey, New York, Delaware, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas had coalesced in the Ohio River Valley, and there was a growing sentiment among them that they had been pushed far enough.

At this time the Ohio Valley and its environs were a vast and abundant wilderness, teeming with game. Bison still roamed its verdant terrain, as did bear, wolves, cougar, beaver, otter, and elk. Most European-Americans had never been beyond the boundary of the Allegheny Mountains and the Ohio River was the demarcation line between two vastly different worlds. Based on the explorations and hunting tales of the legendary Daniel Boone and others, it was rumored to be a paradise on earth, and in many ways it was. However, this was a paradise that demanded blood from interlopers. Daniel Boone himself had narrowly escaped death there on several occasions, and had lost both his eldest son and youngest brother to Indian warriors. And their deaths had not been easy ones. Torture and terror were familiar tactics in wilderness warfare, and Boone's loved ones had suffered terribly before their deaths. He had enjoyed some protection in his travels as the adopted son of the Shawnee Chief Black Fish, but it was no guarantee of a long life in this part of the world, as inter-tribal rivalries and conflict were a part of the fabric there too. As a literary aside, James Fennimore Cooper's "Last Of The Mohicans" was based largely on Boone's actual exploits and adventures.

Warfare between the Native Americans and the Europeans was nothing new in this region. In fact, by 1791, it had been on-going, with only brief interludes of true peace, since 1754. Literally thousands had died beginning with the French and Indian War, followed by Pontiac's Uprising, Lord Dunmore's War, and most lately, the Revolutionary War. The largely Algonquian-speaking tribes of the region had sided with the British in the War of Independence, and with the French in the first war. The two wars in between had been on their own initiative. None of these choices had endeared them to the New Americans. In 1783, the Treaty of Paris settled the peace between Britain and its former colony, resulting in His Majesty's government ceding all of its territory as far west as the Mississippi River to the new American government. And therein lay the rub--the Indians considered these lands as their own to use and live upon and they had not signed any treaty nor been invited to Paris to do so. They did not intend to abide by it.

The idea of a separate Pan-Indian Nation had been growing amongst the various tribes since Chief Pontiac's doomed coalition of tribal nations, and many felt the Ohio River should be their new national border. But, to complicate matters for the intransigent tribes , the Six Nations (a confederacy of Iroquoian tribes consisting of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora) claimed the Ohio Valley as their own, though they did not reside there, and that the largely Algonquian tribes in the region had been subjugated by them and dwelled there under their sufferance. Though there was some truth to the claim of having subdued these neighbors at one time or another, there was little to support their declaration of territorial ownership, a concept largely foreign to Native American society. Nonetheless, the new American government negotiated with them, gaining the Six Nations' blessing for settling the area, while guaranteeing them the inviolability of their own homeland in upstate New York.

Though there were dozens of Ohioan tribes affected by these events, some indigenous to the valley, as well as a number newly arrived there, three stood out in their stiff resistance to the new regime: the Miami, the Shawnee, and the Delaware; each of these led by particularly gifted warriors: Little Turtle, Blue Jacket, and Buckongahelas, respectively. They intended to enforce the line of demarcation and waged a particularly vicious campaign against the whites that crossed the river. By the time President Washington determined to take action, the death toll of westward traveling pioneers had risen to some 1,500 slain.