|

| Not a Big Shot Writer |

My daughter, Bridgid, suggested that my next posting on SleuthSayers address the issue of where I got the ideas that became published stories for me. She assured me that there is a large audience of novice writers, and just plain fiction buffs, that visit authors' blog sites everyday for just such info as this. I countered that this audience was most likely for writers with a slightly higher recognition profile than my own. Strangely, she did not deny this. This was during her Christmas visit and the gifts had already been opened. Next year may be a lean one for her.

My son, Julian, the English teacher (or Professor as he likes to be addressed), gave me a huge compendium containing the works of some short story writers somewhat better known than myself. You may recognize a few of these names: Willa Cather, Joseph Conrad, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, James Joyce, Flannery O'Connor, Edgar Allan Poe, etc, etc...blah, blah, blah. Some of them struck a distant chord with me. The name of this book is,

The Art of the Short Story compiled and edited by Dana Gioia and R.S. Gwynn, and offering insights by the authors themselves on their stories within, or on some aspect of writing them. The 'professor' added, "You should read this." I thought I detected the slightest of smirks on his face (again, this was

after the opening of his gifts from his mother and me).

It seemed to me that, perhaps, my children (who had once been so adorable) were trying to tell me something; it occurred to me that they may have been insinuating that there was room for improvement in my writing efforts, or something along those lines. It is only fair to note, that the two of them act as the unofficial editors (and unwanted critics) of most of my scribblings since they became college graduates. Their older sister, Tanya, lives in Atlanta and has children of her own and therefore no time to pile on with her siblings, thank God. The other two, however, have a certain proprietary air about them when it comes to my so-called writing career.

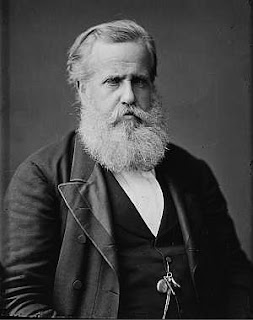

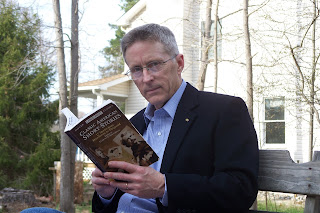

"I've read a bunch of these," I countered. "A whole bunch. Some of them are pretty good. That Poe dude is a little heavy-handed in the prose department though, don't 'cha think?" Take that, professor. His expression was equal parts disappointment and disdain. "Yeah," I went on, "he does guest features on SleuthSayers from time to time...we call him, 'E.A.' for short." No laughter, no smiles...nothing. Kinda like the photo below.

|

| E.A. (Big Shot Writer) |

When the critics finally went away, having stripped the house of most edibles, their mother and I were left behind once more; at least until we should be needed to provide something useful. The 'Book' rested on my nightstand...waiting. After spraining a wrist lifting it, I discovered that I had, indeed, read a number of the stories, though certainly not the majority of them. In fact, as I read, it reminded me of what a wonderful form of expression the short story really is. It also reminded me of why I've always like to write them. You can do things with a short story that just aren't possible in another medium. Imagine

The Yellow Wallpaper or

The Lottery as novels--they would have become bogged down and tedious with detail; diluting their impact. How about,

To Build a Fire? The terrifying urgency of that story would have been lost at book-length. Even, E.A.'s stuff would have collapsed under its own weight had he not confined himself to short stories.

According to the authors of the "Art" the short story is the most recent and modern of literary forms; Nathaniel Hawthorne being credited with its introduction to the English Language in 1837 with

Twice Told Tales. I did not actually know this, but I'm sure the professor did. As a testament to his genius (Hawthorne's, not my son's), many of those tales still read very well today and retain a compelling narrative power. It's astounding how really good writing can transcend the barrier of time and the hurdles of archaic language. Poe manages this pretty well, too.

|

| Nathaniel Hawthorne (another Big Shot Writer) |

Astounding, also, is the number of writers who have specialized in, or written exclusively, short stories. Heed the following roll call: O'Connor, H.H. Munro (Saki), Poe, Hawthorne, Bradbury, de Maupassant, Doyle, Henry, but to name a few. Additionally, writers perhaps better known for their novels, such as Borges, Chekhov, Conrad, Faulkner, Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Joyce, Oats, du Maurier, and Tolstoy contributed mightily to the short fiction realm. When I contemplate the undeniable fact that literary giants such as these believed the short story a worthwhile endeavor, I am heartened to persevere at my modest endeavors.

As I confided to Bridgid and her brother one day: If I only had one story, just one, that ended up being read twenty-five or fifty years from now, or even better, was made mandatory reading in some college class (hopefully one taught by my son; wouldn't that be sweet justice?), I would feel that I had accomplished something. Clearly I'm not in it for the money, though God knows I wouldn't be amiss to a few whopping big paychecks (I give to a lot to charities, you see). So for all of you, my short fiction brethren, take heart and keep writing as we, too, can become big shot writers! Don't let the narrow marketing field discourage you. After all, we write because of our love of the word and, in my case at least, in order to entertain, at my own expense of course, my wonderful children and wife.

As a postscript, I would like to bring your attention back to my photo at the top of the page. You may notice, though it has been subtly framed, that I am holding a really big book of short stories. Now that I have an even bigger one which includes a bunch of foreign authors too, I intend to have another taken. Julian assures me that there's no chance I could look any more pompous with his bigger book, but I'm willing to give it a try even so. He suggests a tweed jacket with leather elbow patches might just do the trick.

I think a pipe would help, as well.