Last month I wrote about

books I dug up recently because I remembered them from my childhood. I ended by

saying "Maybe next time I will talk about childhood favorites I bought

my daughter when she was a kid." But instead I talked about my

non-conversation with a taxi driver. So here we go.

If you are familiar with Crockett Johnson it is probably because of his wonderful books about Harold and the Purple Crayon

which have inspired children's imagination (and the occasional

wall-scribble spanking) for many years. Bill Watterson, the creator of the marvelous Calvin and Hobbes comic strip, also said that Harold was all he knew of Johnson.

The reason he was asked about Johnson is that Calvin bears a certain resemblance to Ellen's Lion.

Both feature a young kid (Ellen is a preschooler, a bit younger than

Calvin) whose best friend is a stuffed animal. In both cases the

beastie has a completely different personality than the kid, but the

animal can't speak if the kid's mouth is covered. (And now that I think about it, it sounds like both artists were describing a child having a psychotic break. But put that out of your mind. Sorry I brought it up.)

What I

like best about Johnson's stories is that the imaginary friend, so to

speak, is the realist in the pair. When Ellen asks the Lion about his

life before they met she wants to hear about steaming hot jungles, but all

he remembers is a department store.

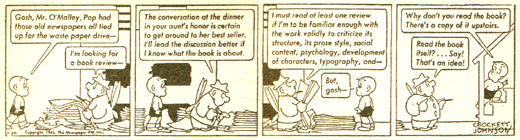

By the way, Johnson also created one of the most brilliant comic strips of all time. Barnaby

ran during the early forties and featured another preschooler who, in

the first episode, wishes for a fairy godmother. Due to wartime

shortages he was instead assigned Jackeen J. O'Malley, a three-foot-tall

fairy godfather with a grubby raincoat, magenta wings, and a

malfunctioning magic cigar. Mr. O'Malley introduces Barnaby to such

characters as Atlas, a three-foot-tall giant (he's a mental giant), some Republican ghosts, and a talking dog who will not shut up.

The other book I hunted down for my kiddo has nothing to do with Crockett Johnson but does mention Atlas. The original one.

d'Auliares' Book of Greek Myths,

written and illustrated by Ingri and Edgar Parin d'Aulaire, started me

on my lifelong love of mythology. Not only are the pictures

unforgettable but the writing is very well done.

One

thing I love about it is how cleverly they slip around, well, the

naughty bits that you might not want to explain to an eight-year-old.

In the chapter on Theseus they explain that Poseidon, god of the sea,

sent a white bull to the island of Crete, which King Minos was supposed

to sacrifice to him:

But Queen Pasiphaë was so

taken by the beauty of the white bull that she persuaded the king to

let it live. She admired the bull so much that she ordered Daedalus to

construct a hollow wooden cow, so she could hide inside it and enjoy the

beauty of the bull at close range....

To punish the king and queen, Poseidon caused Pasiphaë to give birth to a monster, the Minotaur. He was half man, half bull…

Every

adult, I imagine, understands exactly what the dAulaires said that the

Greeks were saying about Pasiphaë, but it goes right over a kid's head. (Did mine,

anyway.)

The book is still in print. Unfortunately the

binding is not as long-lasting as the text and pictures. I have had to

replace it about once a decade.

Ah well, no mysteries

this week, unless you count the mystery religions. Or Mr. O'Malley's

encounter with the fur coat thieves...

Showing posts with label comix. Show all posts

Showing posts with label comix. Show all posts

16 November 2016

The Night The Old Nostalgia Burned Down, Again

Labels:

Bill Watterson,

cartoons,

comics,

comix,

Crockett Johnson,

d'Aulaires,

Lopresti,

mythology

11 September 2013

The Duck Guy

I, too, like Dale, (post of 27-Aug-2013) read a lot of Hardy Boys books. But over time, they came to seem pretty thin, and they weren't a lasting influence. The guy who was in fact an early and lasting influence is Carl Barks.

Who he? you ask, as well you might. Barks was the Duck Guy. He started in 1942, with "Donald Duck Finds Pirate Gold," and for the next thirty years, he wrote and illustrated the duck comics for Disney. This was a very different Donald from the animated cartoons. Barks reinvented him. He also came up with Duckburg itself, Scrooge, Gladstone, the Beagle Boys, the Junior Woodchucks, and the indispensable Woodchuck Handbook.

There were two basic storylines, the exotic and the domestic, with some variations. The exotics were adventure stories, like "The Golden Man," where Donald hares off to South America in search of the rarest stamp in the world---Barks himself was a homebody: he said he was inspired by back issues of NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC. The domestics were broad comedies, Donald the dogcatcher, for example, or his sudden enthusiasms for some new-found craze, like Flippism (which I can't fully explain, but Barks gets it across in a couple of quick brushstrokes).

He got better, too. Both the scripts and the draftsmanship are more and more sophisticated, moving into the 1950's. Some of the big panels are breathtaking, but often it's in the very small details, something that furnishes a room, or the way a static drawing can show Donald in full physical flight. There's a sense of plasticity, if that's a word, a shapeliness in the framing of the images, and in the lack of clutter, although everything has a specific density. I'd like to call it genius. Barks knew how to make a panel chewy, so you had to look more than once.

And the plots. The familiar taken to a level of insane abandon is a favorite device, whether it's a snowball fight or the hunt for Ali Baba's cave. And it's snappy. There isn't any wasted motion. Most of the stories were told in ten pages, six panels to the page, but there were also more elaborate, extended adventures, that took up a whole issue of the Uncle Scrooge line, which was a quarterly title, not monthly. See below.

WALT DISNEY'S COMICS AND STORIES came out every month. The lead feature was a duck story, then a Li'l Bad Wolf, and last, an installment of a Mickey detective serial, usually three parts. Back in the day, a year's subscription cost a buck, and any kid could cadge that up in bottle returns. Remember bottle returns? That was when the newsstand price of a comic book was one thin dime, and so was a raspberry lime rickey at the Linnean Drug soda counter. (Showing my age.) Each issue came to the door in a paper sleeve, and it was like opening a bag of potato chips. You couldn't stop yourself. Instant gratification. And the back issues were just as much fun, too.

The thing about Barks is that you can pick up one of those duck stories today, and read it again, and get the same rush. He's that good. It stands the test of time. And in fact, this is the guy who showed me how to tell a story. We outgrow the Hardy Boys, or Nancy Drew, all due respect, but Barks will never grow old. His stuff is still as fresh as when I was in short pants.

Who he? you ask, as well you might. Barks was the Duck Guy. He started in 1942, with "Donald Duck Finds Pirate Gold," and for the next thirty years, he wrote and illustrated the duck comics for Disney. This was a very different Donald from the animated cartoons. Barks reinvented him. He also came up with Duckburg itself, Scrooge, Gladstone, the Beagle Boys, the Junior Woodchucks, and the indispensable Woodchuck Handbook.

There were two basic storylines, the exotic and the domestic, with some variations. The exotics were adventure stories, like "The Golden Man," where Donald hares off to South America in search of the rarest stamp in the world---Barks himself was a homebody: he said he was inspired by back issues of NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC. The domestics were broad comedies, Donald the dogcatcher, for example, or his sudden enthusiasms for some new-found craze, like Flippism (which I can't fully explain, but Barks gets it across in a couple of quick brushstrokes).

He got better, too. Both the scripts and the draftsmanship are more and more sophisticated, moving into the 1950's. Some of the big panels are breathtaking, but often it's in the very small details, something that furnishes a room, or the way a static drawing can show Donald in full physical flight. There's a sense of plasticity, if that's a word, a shapeliness in the framing of the images, and in the lack of clutter, although everything has a specific density. I'd like to call it genius. Barks knew how to make a panel chewy, so you had to look more than once.

And the plots. The familiar taken to a level of insane abandon is a favorite device, whether it's a snowball fight or the hunt for Ali Baba's cave. And it's snappy. There isn't any wasted motion. Most of the stories were told in ten pages, six panels to the page, but there were also more elaborate, extended adventures, that took up a whole issue of the Uncle Scrooge line, which was a quarterly title, not monthly. See below.

WALT DISNEY'S COMICS AND STORIES came out every month. The lead feature was a duck story, then a Li'l Bad Wolf, and last, an installment of a Mickey detective serial, usually three parts. Back in the day, a year's subscription cost a buck, and any kid could cadge that up in bottle returns. Remember bottle returns? That was when the newsstand price of a comic book was one thin dime, and so was a raspberry lime rickey at the Linnean Drug soda counter. (Showing my age.) Each issue came to the door in a paper sleeve, and it was like opening a bag of potato chips. You couldn't stop yourself. Instant gratification. And the back issues were just as much fun, too.

The thing about Barks is that you can pick up one of those duck stories today, and read it again, and get the same rush. He's that good. It stands the test of time. And in fact, this is the guy who showed me how to tell a story. We outgrow the Hardy Boys, or Nancy Drew, all due respect, but Barks will never grow old. His stuff is still as fresh as when I was in short pants.

Labels:

Carl Barks,

comics,

comix,

David Edgerley Gates,

Disney,

Donald Duck,

Hardy Boys

Location:

Santa Fe, NM, USA

16 October 2011

The Mystery of Superheroes

by Leigh Lundin

My

kryptonite is the common cold. After struggling more than a week with a

blasted cold, I ventured out with friends for soup and salad and then

movies. Artist friend Steve Rugg loves comic action heroes brought to

the silver screen, and one recent addition is Captain America.

My

kryptonite is the common cold. After struggling more than a week with a

blasted cold, I ventured out with friends for soup and salad and then

movies. Artist friend Steve Rugg loves comic action heroes brought to

the silver screen, and one recent addition is Captain America.I liked the angst-ridden Spiderman and the dysfunctional sibling-like rivalry between Fan4's Torch and the Thing, but other action heroes didn't do much for me. Indeed, I didn't know Captain America possessed any extra-physical powers, but I since learned the movie closely follows the original 1941 story line:

Early in WW-II, the Army injected Steve Rogers with a sort of precursor anabolic steroid to turn him from a 98-pound weakling into a superdude. Otherwise unarmed, he carries a frisbee-like shield made of something like vibraphonium, batteries not included. (Okay, okay, it was actually called vibranium.)

The evil wicked baddie in the Captain America movie was a Nazi named Schmidt AKA Red Skull. For all the world, he reminded me of Jim Carrey's The Mask. I kept expecting him to whirl, pose, and exclaim "Smokin’!"

|

| German Horton Ho XVIII |

Even if a movie-goer isn't a fan of comic action heroes, Captain America can be enjoyable. Most of us weren't alive during World War II, but from the outside looking in, the film's ambience appears superb from the era graphics to the burlesque stage shows.

Pulp Mystery Comix

From the early days, there's long been a link between 'comix' and crime fiction. Obviously action heroes battle criminals, but the ties run deeper than mere pulp fiction. Like several detectives, Deborah Elliott-Upton's inamorato, Nick Carter, crossed back and forth from radio to movies to comic books. The Falcon crossed boundaries as did everyone's favorite, the Shadow. For reasons I never understood, Batman got his start in Detective Comics.

Great debate centers around superheroes– whether to wear a cape, whether to wear underwear on the outside, how tight are tights, and do primary colors really make the best camouflage? Radiation appears critical in the development of superheroes. It kills ordinary people, but it grows muscle mass in the comicbookly-predisposed.

|

| Fantastic Four |

Graphic novels require a subtle balance of fairness, or rather an initial imbalance of unfairness, which should tilt heavily in favor of the bad guys. I never bothered to learn why movie fans and critics didn't like the Fantastic Four, but the failure for me was the good-to-bad four-against-one scenario. In the comic books, much of the focus was on the friends 'n' family relationship of the FF, but we need to spot the bad guys a few points before the game's worth playing. That didn't happen in Fantastic Four. Even the perfect performance of Michael Chiklis couldn't save the FF from ultimate Doom.

I was too young for the height of the Doc Savage novels, but an underlying imbalance marred that famed series for me. Savage was smarter than his smartest guy, faster than his fastest, stronger than his strongest. In the two or three stories I tried to read, Doc ended up rescuing them. What was the point of having a team if they got themselves captured like silly schoolgirls?

As an Author

My knowledge of comics and graphic novels is small compared to Steve Rugg or John Floyd, but I have worked on a couple, most recently the English version of Tentara, a sweeping epic starring a little girl, Angal. The fans and subjects of graphic novels are overwhelmingly male and with the possible exception of Wonder Woman, girls seldom flock to action comics.

This mirrors athletics audiences. Women are very selective what they watch and participate in whereas males consume nearly anything sporting. Savvy promoters carefully position women's sports and graphic novels, knowing their female audience may fall short but male spectators could make up for that shortfall.

I enjoy ventures into graphics novels. Once before during a flu-wracked fever, I wrote an unusual story, sort of (don't roll your eyes) an ancient Chinese fable with romantic overtones. It's a pretty good 10k-word story but it's so unusual, I don't have a clue whom to market it to. It doesn't fit into any particular genre and at the moment it's slightly too risqué for children. Recently it dawned on me– it would make a good graphic novel. That's another can of worms: As I've learned, my experience is just large enough to realize difficulties but not great enough to know the solutions.

Seduction of the Innocent

During the middle 1950s, critics sounded the alarm that comic books led to juvenile delinquency. Congress formed another of its endless subcommittees, the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency, and held national hearings on the evils of comics.

One of the most heard voices was that of psychiatrist Fredric Wertham, author of an article in Collier's, 'Horror in the Nursery', and the 1954 book, Seduction of the Innocent, subtitled 'the influence of comic books on today's youth.' As an expert witness, Wertham held that violence was obvious, but that images of nudity were hidden in comic panels. He contended Superman was a fascist, Batman and Robin were gay, and Wonder Woman was a lesbian bondage babe. In particular, the German-American Wertham appeared to target beloved artists such as Al Feldstein and Harvey Kurtzman. (Wertham's later writings against racism and violence were largely overshadowed by his anti-comic crusades.)

Even Oscar Wilde noted the poor parenting skills of Americans, but in the post-war fifties, society sought other answers, any answer at all. They blamed rock 'n' roll, they blamed pool halls in River City, they blamed everything except absentee (or simply absent) parenting. Comics became one more target.

Those in the industry derided the hysteria, but parents burned comic books in the streets and the mature comic industry plunged. The entire pulp publication business suffered and dozens of venerable series bit the dust.

One of the primary targets was EC Comics, which owned such titles as Tales from the Crypt, The Vault of Horror, The Haunt of Fear, Frontline Combat, Two-Fisted Tales, Weird Science, and the noirish Shock SuspenStories and Crime SuspenStories. Intended for older audiences, themes often dealt with war, death, racism, anti-Semitism, drugs, sex, and political corruption which disturbed many in the McCarthy era.

On the verge of bankruptcy, EC Comics folded most of its comics, but its owner, William Gaines wreaked a sort of revenge with Mad Magazine that subverted such vulnerable children as me. Ironically, Wertham's original and intact copies of Seduction of the Innocent (its own bibliography was censored, ripped from most books), demand top prices at comic conventions. But there's one more story about EC and William Gaines.

In the throes of survival, EC Comics turned to medical and office dramas, but couldn't make the formulae work. Fighting censorship, Gaines strove against the restraints of the Comics Code Authority, which enforced rules that the words 'horror', 'terror' or 'weird' couldn't be used on comic book covers, wiping out many EC titles. Without the CCA seal of approval, wholesalers refused to carry EC's comics. One of those titles was Weird Science Fantasy, which EC tried renaming Incredible Science Fiction, keeping the WSF sequential numbering scheme.

Line in the Sand

The final battleground became the February 1956 issue, Nº 33 of Incredible Science Fiction. After the CCA rejected one story, Gaines substituted another, titled Judgment Day. In it, an astronaut visits Cybrinia, a planet of robots that seeks admittance to the Galactic Republic. He finds the robots indistinguishable except that some are sheathed in orange and some blue. The orange have come to dominate the others, reserving privileges for themselves and subjecting the blues to servitude.

The astronaut determines the bigotry is grounds to deny them admittance to the Republic. In the final panel, the astronaut pulls off his helmet, revealing he is a black man.

"This really made 'em go bananas in the Code czar's office," wrote comics historian Digby Diehl, speaking of Judge Charles Murphy, who couldn't stomach the idea of a black astronaut. Al Feldstein responded, "For God's sakes, Judge Murphy, that's the whole point of the Goddamn story!"

Diehl goes on to say "When Murphy continued to insist that the Black man had to go, Feldstein put it on the line. 'Listen,' he told Murphy, 'you've been riding us and making it impossible to put out anything at all because you guys just want us out of business.' [Feldstein] reported the results of his audience with the czar to Gaines, who was furious. [Gaines] immediately picked up the phone and called Murphy. 'This is ridiculous!' he bellowed. 'I'm going to call a press conference on this. You have no grounds, no basis, to do this. I'll sue you.'"

EC Comics managed to get the comic out, but it was the last EC Comics would publish. At last you know why they were in the superheroes business.

Labels:

Captain America,

comics,

comix,

Leigh Lundin,

Mad Magazine,

William Gaines

Location:

Orlando, FL, USA

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)