|

| My published works. Photo by Tamara Belts |

My third professional job was at a university. I was still a government documents librarian. One day an older community member wandered into my department.

"So you get federal documents here."

"That's right."

"Do you have classified publications?"

I laughed. "I can barely get them to send us tax forms."

But let's talk about something they did send us. One day David, my assistant, placed one newly-arrived publication on my desk, as opposed to the usual location.

I figured out why pretty quickly. A the bottom of the cover it said: FOR LAW ENFORCEMENT USE ONLY. There are certain kind of publications that are not supposed to be sent to depositories, and that is one of them.

What's disturbing is that we are thousands of miles from the GPO. Many libraries must have received that publication before we did, but David was the first to spot the problem. Hmm.

The publication was about an organization that does not approve of certain activities and allegedly had a habit of blowing up buildings in which those activities took place. This publication explained to law enforcement officials the methods these people had allegedly been using.

This was before email so I called the GPO. "You didn't mean to send us that publication."

"Why not?"

"Because it's full of diagrams of explosive devices. It's basically a manual for bombmakers."

"We'll get back to you."

Later that day they did. "You're right. Destroy it." Now, I should explain that any publication the federal government sends for free to a depository library remains federal property. They can demand it back or tell us to shred it if they want. (What they can't do, minus a court order, is ask who has read it. Librarians are fussy about that.)

So I destroyed the publication.

A few days later I got a letter from GPO, addressed to all depository libraries. It said that the publication was sent by mistake and we should return it immediately.

Back to the phone. "You told me to destroy it. How am I supposed to return it?"

"We'll get back to you."

They did. "Send us a letter explaining how you destroyed it."

I was sorely tempted to say "I used the method shown on page seven." But who needs that kind of trouble?

I have lost track of how many offices I had in this library. At least eight. At one point my desk was in an open area. A fellow employee told me that as a supervisor I needed an enclosed office. "In case you need to yell at someone."

|

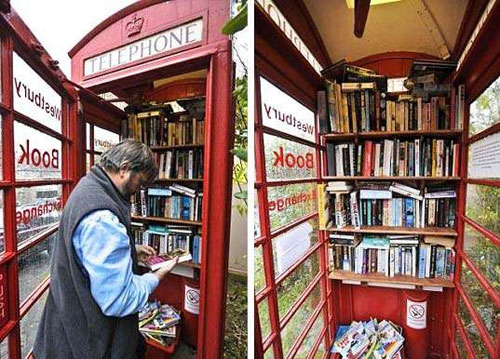

| The view from my last office. |

And speaking of moving, I supervised the shifting of the 200,000 government publications at least five times. On the day we finished one move we had the windows open and a squirrel hopped in. He went straight to the A 13's: the publications of the Forest Service. "Boy," I thought, "if only the students could find their way as easily as you!"

I wish like hell I could tell you the exact day this happened. It was one of the most significant dates in my career. I was at the reference desk and a man asked "Do you have the German railroad timetables?"

"Wow," I said. "No. The best I can do is give you the phone number for the German consulate in Seattle. But wait! There's something brand new called the World Wide Web and we can access it from this computer."

Google didn't exist yet. I think I went to Altavista. He typed in the words German railroad timetables, in German.

And boom, there they were, your choice of English and German. Up-to-date and free.

"Okay," I said. "Right now, this moment, my job just changed completely."

And it had. For example, my library no longer has a reference desk because people don't come with easy questions anymore, the kind Google can answer. Now we specialize in helping with longer research projects. But students still need help.

A student had been asked to find out everything she could about someone - anyone - who lived in our county in 1880. I took her to the microfilm reels for the 1880 census, showed her how to use them and went back to my desk.

Soon she reappeared with a question: "What's a demimonde?"

I knew the answer but, following the old rule, I took her to a dictionary to check that it indeed meant prostitute.

She had found an entire building full of demimondes: a brothel. She was thrilled.

I told this to another librarian who nodded gravely. "In Seattle they called them seamstresses."

Most of the librarians served as liaisons for academic departments. Among other things, that meant teaching sessions on library resources. I had recently taken that role for a new subject when I was strolling across campus and a professor saw me. His eyes lit up. "Rob! Looking forward to your teaching my class tomorrow!"

"Me too!" I assured him. Then I rushed back to my office and checked my calendar. No mention of a class. Had I reserved a classroom? No.

So who was this professor who was expecting me? I knew some of the profs in that department by sight, but not all. This was before the time when you could find a picture of everyone in the world by going to the Web. (I especially like LudditeHermitGallery.com) I narrowed it down to about four.

I called the department secretary (if department secretaries ever went on strike at any university, the place would collapse within a day). "You gotta help me," I begged.

Between us we figured out it had to be Professor X. I sent him a grovelling apology. Which class was I supposed to be teaching, and what did he want me to cover?

He wrote back with his own apology. He had gotten me confused with a different Rob.

Whew.

In my city we only get measurable snow in about half the winters. 1996 was one of them. Woke up one December morning to well over a foot of white stuff. My city didn't own a snowplow.

I normally bike to work; that wasn't going to happen. Driving was out and the buses weren't running. So I walked the three miles.

All the way I had my headphones on and the disk jockey kept listing an ever longer list of closures. I should explain that back then the university seemed to take a perverse pleasure in staying open whatever the conditions were. They always sent out po-faced statements urging personnel to decide for themselves if it was safe to come to work, but they wouldn't close (so workers who didn't show up wouldn't get paid).

So I am almost finished with my two-hour trudge and am starting up the hill to the campus proper when the DJ says: "Here are the closings." Dramatic pause. "The university is open. That's it. Everything else in town is closed. When the world ends the school paper will be the only place that reports it because the university will refuse to close."

The boss bought pizza for everyone who showed up. (And someone actually drove out to pick it up.) The next day the university closed and the DJ bragged that he shamed them into it.

One day a young woman told me she was having trouble finding sources for a paper. I had developed a quick technique for finding out how far a researcher had gotten and I applied it.

"Have you tried Database X?"

"No."

"Have you tried Database Y?"

"No."

"Have you tried Database Z?"

She burst into tears and ran out of the room. I couldn't coax her back.

I never used that technique again.

One of our regular patrons was a Vietnam vet who was having trouble with the VA. As he told the story he wanted to receive disability payments because his time over there drove him crazy. The VA's defense was - again, according to him -- that he was already crazy when the army drafted him. Not a great argument.

A member of the public is welcome to use our collection and anyone could borrow our federal publications, if they showed ID. This veteran wanted to borrow some but he refused to show his ID because he thought the VA might be tracking what books he read.

I told him that didn't match my experience of reality but I respected his right to his own. Nonetheless, he couldn't borrow the documents.

He used them, over several years. I don't know how his case turned out but he started taking better care of himself and bringing in fellow vets whom he helped use the docs. I counted that as a win.

The worst and the best: someone stole more than 600 pages out of our old Congressional Serial Set volumes. After more than a year and a half of sleuthing by various people at our university we got the evidence that led to the thief's conviction. You can read all about it here and here.

One day I picked up the book on Occupations from the 1920 Census and read about "Peculiar occupations for women." The introduction explained that census takers had reported women in a lot of occupations that women obviously could not have been working in, like masons and plasterers. And so, the census bosses explained solemnly, the records were carefully examined and if they could figure out what the mistake was they corrected it. Or should I say if they figured out what the "mistake" was they "corrected" it. And how many female pioneers in their fields were erased from history?

Years later, that led to my first nonfiction book.

One night I took my family to the best ice cream parlor in town. The young man behind the counter said: "Last year you helped me with a research paper. Not only did I get an A but the teacher kept it to use as an example. Your ice cream is on me."

The super chocolate tasted particularly sweet that night.

Back in January I taught a workshop on library resources and, as usual, handed out a quick feedback form. One student wrote: "You introduced me to subjects I didn't even know to ask about."

My pleasure, friend.

I would like to end by saying something I have not said in forty-one years on the job: Shhhhh!