|

| Spotted in an airport. |

This used to be a time of year when we humans gathered together in rooms to shut out the cold. We lifted glasses to each other. We ate happily. We laughed. We even breathed freely and shamelessly in each other’s presence.

|

| A Harry Potter text, by one Libatius Borage. |

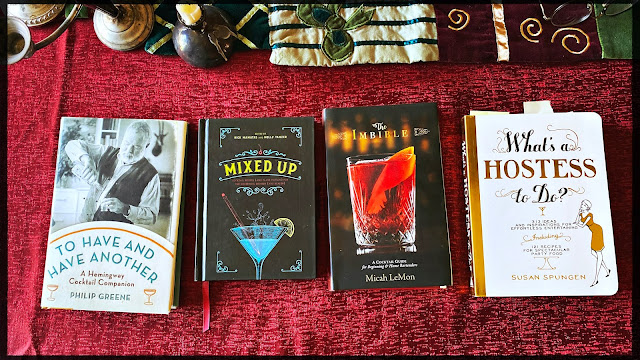

I’ll start with the one mostly closely aligned with short stories. Mamatas and Tanzer have pulled together a lovely collection of 17 short pieces by writers working in various genres. Each story references a cocktail or two, whose recipes are then shared after the story, 25 recipes in all. You’ll find plenty of classics here—the Old fashioned, martinis, the negroni, etc.—but also fashionable overexposed beverages such as the Moscow mule. This time of year, you might want to check out their recipe for a smoking bishop—the beverage reformed Scrooge promises his man, Cratchit, at the end of the Dickens tale. Before this book came along, I tried to recreate that beverage years ago, and bungled it, mostly because many of the traditional ingredients do not have easy modern substitutes. This recipe, accompanied by Robert Swartwood’s hilarious tale, goes down easy. This is a small, attractive volume suitable for gift giving.

The Imbible: A Cocktail Guide for Beginning and Home Bartenders, by Micah LeMon (University of Virginia Press, 2017).

The book is so beautiful that you will probably not want to keep it on your bar while you are mixing your beverages. It’s a standard-sized hardcover with a coffee table feel. Lavish photographs on glossy paper throughout. In the intro, LeMon tells us that he was raised in an Evangelical and Pentecostal Christian family. So of course for one of his first jobs he ends up behind a bar, where he has no idea what he’s doing. “I thought God might strike me dead with lightning, give me leprosy, or inflict some equally biblical punishment just for touching the stuff,” he says. Luckily for us, he studies the craft and distills every great cocktail to three critical ingredients: a spirit, something sweet, and something bitter or sour. Using this as his template, he then marches us through a multitude of classic drinks, showing us how you can easily mix and match to arrive at something delightfully quaffable. If you’re ever in Charlottesville, Virginia, you’ll find him tending bar at The Alley Light.

To Have and Have Another: A Hemingway Cocktail Companion, by Philip Greene (TarcherPerigee, 2017). Boy howdy, that Ernest Hemingway fellow sure liked to drink, huh? I like this book because it doesn’t just talk about Hemingway’s prose, and the beverages that crop up in his writing. Along the way, we also get stories about the actors and production anecdotes associated with the movies that were made out of his books. There are plenty of movie posters, artwork of long-gone nightclubs and bars, and candids of Bogie and other actors to spice up the mix. And yes, absolutely, you will find a ton of recipes to fortify yourself before you step into the ring with a bull.

What’s a Hostess to Do? 313 Ideas and Inspirations for Effortless Entertaining, Including 121 Recipes for Spectacular Party Food, by Susan Spungen (Artisan, 2013).

Not a drink book, per se, but absolutely indispensable for those of use who want to throw a party but whose imagination fails them just as they depart the tortilla-chips-and-salsa aisle. Spungen walks us through five very different entertaining scenarios—the cocktail hour, the buffet, the dinner party, holiday entertaining, and outdoor parties—and proceeds to blow your mind with her food editor brain. She presents two cocktail menus side by side, asking: “What’s wrong with this [first] menu?” Complicated cocktail party menus force guests to juggle too many things: napkin, silverware, plate, and drink. The best snacks for these sorts of parties can be eaten with one hand. Duh, but I’d never think to drill down on that. This is a fine paperback for hostesses (and hosts!) alike.

If all else fails, you could just throw caution to the wind and treat yourself to this little bag of Mixology Dice. Toss ‘em, assemble the ingredients, and Good Luck quaffing the hand fate dealt you.

I wish you all the best this season, however and whenever you choose to raise your glass.