I’d like to suggest a different division that encompasses a lot of these varieties, namely closed vs open plotting. By closed, I mean something like the traditional mystery which, despite its relative modernity, has classical antecedents. Back in the day, Aristotle talked up the unities of time, place, and action, basing his analysis on the Greek tragedies that favored a tightly focused action with a few protagonists in one locale. Contemporary short mystery stories, anyone?

I’d like to suggest a different division that encompasses a lot of these varieties, namely closed vs open plotting. By closed, I mean something like the traditional mystery which, despite its relative modernity, has classical antecedents. Back in the day, Aristotle talked up the unities of time, place, and action, basing his analysis on the Greek tragedies that favored a tightly focused action with a few protagonists in one locale. Contemporary short mystery stories, anyone?The Greeks also liked to begin in media res, in the heart of the action, another favorite device of most modern mysteries, not to mention thrillers.

Beyond this, we see an interesting split. If the closed mystery may no longer be set in the country house or the isolated motel, it has a small universe of suspects and usually a fairly compact geographic area. This is particularly clear in the various UK mysteries that adorn PBS each season. Vera may be set out on the windswept moors and empty sands, but there are rarely more than five real suspects and, in this show at least, they are as apt to be related as in any Greek tragedy.

Midsomer Murders is also fond of a half dozen suspects, mostly unpleasant people who will never be missed. Ditto for Doctor Blake who, with all of Australia, sticks close to Ballarat and, yes, the handy five or so possibilities. Clearly, the attractions of this sort of story for the TV producers are the same attributes that pleased the Athenian town fathers: compact locations, smallish casts, one clear action. The emphasis is on the puzzle factors of mysteries, and at their best such works are admirably neat and logical.

The open mystery takes another tack, flirts with thriller territory, and likes to break out of confined spaces both geographic and psychological. If it has ancestors, they’re not the classically structured tragedies, but tall stories, quest narratives and, if we need a big name, Shakespeare, who loved shipwrecks and runaways and nights in the woods, as well as mixing comedy and tragedy and all things in between.

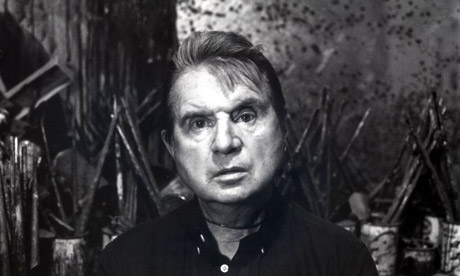

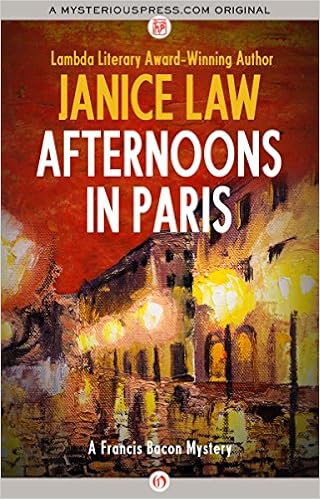

The open mystery takes another tack, flirts with thriller territory, and likes to break out of confined spaces both geographic and psychological. If it has ancestors, they’re not the classically structured tragedies, but tall stories, quest narratives and, if we need a big name, Shakespeare, who loved shipwrecks and runaways and nights in the woods, as well as mixing comedy and tragedy and all things in between. I’ve thinking about this divide for two reasons. First, I just finished what will be the last novel in the second Francis Bacon trilogy, Mornings in London. I really wanted a little bow to the great British tradition of the country house mystery, and I managed a country mansion – just the sort of place Francis hates – and a nice half dozen suspects. I had a victim nobody much liked and rather a nice crime scene, and I must confess that neither Francis nor I was really happy until I could get us both back to London and off to other places less claustrophobic.

I’ve thinking about this divide for two reasons. First, I just finished what will be the last novel in the second Francis Bacon trilogy, Mornings in London. I really wanted a little bow to the great British tradition of the country house mystery, and I managed a country mansion – just the sort of place Francis hates – and a nice half dozen suspects. I had a victim nobody much liked and rather a nice crime scene, and I must confess that neither Francis nor I was really happy until I could get us both back to London and off to other places less claustrophobic.Turns out what I had long suspected was true: I’m not cut out for tidy and classical and ingenious puzzles. And I don’t write that way, either. I like to meander from one idea to the next, a method of composition much more conducive to glorified chases and quests than to Murder at the Manor. Too bad.

The other reason I got thinking about closed vs open plots was a quick dip into a Carl Hiaasen novel, one of his orgies of invention that spins off in every possible direction without somehow losing a coherent plot. If Agatha Christie is still the godmother of every good puzzle mystery, Hiassen’s satiric crime romps have certainly taken chases, quests, bizarre personalities, and imaginative disasters about as far as they can go.

The other reason I got thinking about closed vs open plots was a quick dip into a Carl Hiaasen novel, one of his orgies of invention that spins off in every possible direction without somehow losing a coherent plot. If Agatha Christie is still the godmother of every good puzzle mystery, Hiassen’s satiric crime romps have certainly taken chases, quests, bizarre personalities, and imaginative disasters about as far as they can go. I wonder now if writing style is inevitably connected with a certain type of mystery. Perhaps those who compose traditional, classically inspired mysteries are the same clever folk who can plan the whole business from the start. And maybe those of us with less foresight are inevitably drawn to a chase structure with a looser time frame, wider real estate, and more characters.

I wonder now if writing style is inevitably connected with a certain type of mystery. Perhaps those who compose traditional, classically inspired mysteries are the same clever folk who can plan the whole business from the start. And maybe those of us with less foresight are inevitably drawn to a chase structure with a looser time frame, wider real estate, and more characters.

No, not that one, this one:

No, not that one, this one: