There’s an old saying that goes, “See you in the funny papers,” which, I have to admit, I never quite got. I mean, how are you going to see me in the funny papers? I’m a real, live, three-dimensional sort of guy. I must also be a literal kind of guy because now I find that the impossible has happened—I’m in the funny papers! That’s right. I find that I’ve been reduced (some might say enhanced) to two dimensions and basking in the reflected glory of none other than that venerable crime fighter, Dick Tracy! Lest you doubt, I’ve attached proof of my brief appearance.

There, see me? I’m the thin dude in the Hall Of Fame box. It appears that amongst Dick’s many skills and talents at detection, he has also honed an appreciation of fine crime writing—mine… amongst others it seems. Can you believe he also honored some dude named Wambaugh in a previous issue? What kind of name is that for a writer? Get a clue, Wambaugh.

When I got the news it was via a forwarded email from Janet Hutchings at Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine. It being a weekday, I was hard at work hammering out my next story when, during a brief lull in my creativity I checked all my social and communication media. Half an hour later, I’m reading a very kind note from a police sergeant named Jim Doherty telling me of my inclusion in Dick Tracy’s Hall of Fame. He had also attached the comic strip. Jim, as I learned, is the police technical advisor to the comic strip’s creative team.

To say that I was blown away would be putting it mildly. Having spent a big part of my adulthood as both a cop and a writer, this inclusion rang all the bells and blew all the whistles for me. I loved it. And it’s great fun to boot.

But that’s enough about me. Though you probably couldn’t tell, I intended my little victory dance to serve as an introduction to my new friend and colleague, Sgt. Jim Doherty, the person most responsible for my induction into the Hall of Fame. On my honor (which is now unquestionable), Jim and I have never met, and he only knew of me through my writing. It was he that submitted my name and bio to the editors, and it was on his recommendation that I was accepted. May his name be sung in the mead halls of Valhalla forevermore.

Jim, as mentioned earlier, is both a police sergeant and technical advisor, but he is also a writer of crime fiction himself. So, I thought it might be interesting if he shared with us a bit about his own background, as well as his relationship with the square-jawed Detective Tracy and his crime-busting comic strip. I think you’ll find it interesting.

Thank you for the introduction, David.

It might seem odd to be discussing a comic strip character on a blog devoted to the mystery genre, until one considers that Dick Tracy’s as important a figure to crime fiction as he is to the comics medium.

Leave aside the obvious fact that, with the exception of Sherlock Holmes himself, Tracy’s the most famous detective in any fictional medium. Leave aside that, like Holmes, he’s a multi-media star, successful in movies, novels, TV and radio, stage productions, and just about any other story-telling medium you can imagine.

Forget about all that and look at him:

The rugged features. The snap brim fedora. The trench coat. Comics are a visual medium, after all, and that being the case, it’s clear that our whole idea of what a hard-boiled sleuth is supposed to look like comes to us direct from Tracy. Every time we think of how cool Humphrey Bogart, Robert Mitchum, Alan Ladd, Jack Webb, or Dick Powell look in that particular ensemble, we’re admiring a look that Tracy’s creator, Chester Gould, invented, or at least connected to crime fiction, as indelibly as Sidney Paget connected the deerstalker cap and the Inverness cape in the pages of The Strand Magazine.

And imagine about how many people must have been introduced to crime fiction through Tracy. Most mystery fans, at least in the US, will probably mention the Hardy Boys or Nancy Drew when asked how they first got started, but, how many of them, even before they knew how to read, thrilled to the four-color adventures of the most famous of all fictional cops. I know one of my fondest memories is of my dad reading Dick Tracy to me years before I even knew how to read. Aside from turning my into a mystery fan, and eventually a mystery writer, Tracy also clearly had an influence on my choice of day job (though, being Irish, and having a lot of law enforcement types in my family Tracy was, perhaps, not the only influence).

I was fortunate enough to get involved in with Tracy professionally, or at least semi-professionally, when two guys I knew through the Internet, both of them well-known comics professionals, decided to start a web page called Plainclothes as a tribute to the famed law enforcement icon. (When Chester Gould first conceived the strip, he called it Plainclothes Tracy).

Mike Curtis, who had briefly been in law enforcement himself (he once served as a deputy in the Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Office), started in the business writing scripts for Harvey Comics about character like Casper the Friendly Ghost, Richie Rich, and Wendy the Good Little Witch. Later he would form his own company, Shandafa Comics. Though an admirer of Dick Tracy, Mike’s first love is really Superman, and he owns one of the biggest collections of memorabilia devoted to the Man of Steel in the country.

He’d formed a friendship with legendary comics artist Joe Staton, who, since he got his first professional job in 1971, has been so active in the business it’s easier to list the characters he hasn’t drawn, than those he has. From Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and Green Lantern for DC to the Hulk, Captain America, Phoenix, and the Silver Surfer for Marvel, to say nothing of work for just about every other comic book company in the US, including Charlton, Western, Comico, First, etc., etc. etc.

The one character Joe always longed to draw, but never got a chance to, was Dick Tracy. Or make that rarely got a chance to. He’d done a comic book story for Disney in the early ‘90’s to tie in with the Warren Beatty film, but it never got published due to the rights being clouded. And he’d done some covers for books collecting reprints of the old strips. But he’d never gotten a chance to do the strip, or even a regular comic book series.

Mike had heard that Dick Locher, the Pulitzer-winning artist/writer who had been drawing the strip since 1983, and writing it since 2005, might be retiring.

He suggested that he and Joe do the website, not only as a tribute to the character, but as a sort of high-tech audition, in case Tribune Content Agency, the syndicate that distributed the strip, really was looking for someone to replace Locher. The main attraction on the Plainclothes website was an original Tracy comics story, done in daily newspaper strip format. This was accompanied by articles, original artwork, and prose stories about the character.

Knowing that I was a cop, a Tracy admirer, and a mystery writer, Mike invited me to contribute two prose stories featuring Tracy. I was at the point where I was actually getting paid to write stuff. I’d had two books published, a collection of true-crime articles, Just the Facts, which included a piece called “Blood for Oil,” about the Osage Indian Murders of the 1920’s which won a Spur from the Western Writers of America, and a study of the creator of iconic private eye Phil Marlowe, Raymond Chandler – Master of American Noir. Writing for free seemed, on the surface, like a step back.

On the other hand, my only novel, An Obscure Grave, though a finalist for a British Crime Writers Debut Dagger Award, was still unpublished, and how many chances would I ever get to write about my favorite detective?

It turned out that the Tribune folks were aware of us. And, though our use of the character could be construed as a copyright violation, they were inclined to look at it as an audition, just as we hoped. It turned out that Mr. Locher really was retiring. On the basis of the work displayed in Plainclothes, Mike was hired to write the actual strip, Joe to illustrate it. Mike invited me to be the police technical advisor, since I’m still an active cop, and I live in Chicago (the unstated, but obvious, setting for the strip).

The first person to have that job was a fellow named Al Valanis, a respected detective in the Chicago Police who has the distinction of being one of the first forensic sketch artists in the history of law enforcement. He created a new feature in Tracy that’s become almost as familiar to fans as Tracy’s two-way wrist communication device. “Crimestoppers’ Textbook,” a panel at the beginning of every Sunday strip that gave safety tips for cops, crime prevention tips for citizens, and the occasional pithy editorial comment. As the new technical advisor, I was also to write the copy for “Crimestoppers.”

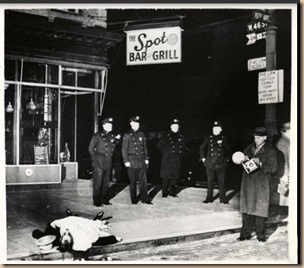

A few months into the gig, I had an idea for a new feature that would occasionally replace “Crimestoppers.” A feature that would profile a noteworthy real-life police officer, to be called “Dick Tracy’s Hall of Fame,” appearing roughly once a month. Over the years, we’ve honored such famed law officers as Eliot Ness, Frank Serpico, Robert Fabian of the Yard, Mary Sullivan (the first-ever female homicide detective), Eugene Vidocq (the founder of the Sûreté), and Bill Tilghman (the greatest of all frontier lawmen).

During this last year, being a policeman who writes crime stories, I had the notion of building the “Hall of Fame” entries for 2015 around a particular theme, cops who also write cop fiction. A few of the more obvious choices have been Joseph Wambugh, William Caunitz, Maurice Procter, and A.C. Baantjer.

But police work isn’t carried out exclusively on big city streets. And crime fiction doesn’t exist only in novels. And so, when I conceived the notion of devoting a year’s worth of Hall of Fame inductees to cops who were also fictioneers, small-town police chief and short story ace David Dean was one of the first persons I thought of.

I’ve admired David’s stories for years, and was pleased to learn that, upon retiring from the Avalon Police in New Jersey, he intended to start writing novels. His first book-length fiction, The Thirteenth Child, was a first-rate genre-crossover, effectively blending the elements of a realistic police procedural thriller with a supernatural horror novel. I couldn’t put it down.

|

|

Maybe if his hair was dark instead of sandy, or if he changed out of the uniform and into a business suit, trenchcoat, and snap-brim fedora, I’d be able to put my finger on just who it is he puts me in mind of.