Many readers here know I teach Crafting a Novel at Sheridan College in Suburban Toronto. (I started teaching fiction writing there before the wheel was invented. We had to push cars uphill both ways to get them to campus...okay, I'll stop now.)

Students often ask me how to get a novel published. I say: "Walk out of this classroom right now and become a media personality."

Everyone in the class laughs. But it's no laughing matter, really. Most of the bestselling crime authors in Canada were media personalities first. It's no coincidence. Being a newspaper or television 'name' gives one a huge visibility advantage. You leap the slush pile. And chances are, you know someone who knows someone in publishing.

But launching a new career doesn't work for all of us, particularly if we are mid-career or soon to qualify for senior's discounts. (Of course, you could still murder someone and become a celebrity. I have a few names handy, if you are looking for a media-worthy victim...)

In order for a publisher to buy your book, they have to read it first. I know at least one publishing house that receives 10,000 manuscripts a month. How in Hellsville can you possibly get noticed in that slush pile?

Here's how: Develop street cred by publishing with magazines!

How I got my start:

In 1989, at the tender age of twenty plus n, I won a Canadian Living Magazine fiction contest. (Canadian Living is one of the two notable women's magazines in Canada. Big circulation.) After that, I pitched to Star Magazine (yup, the tabloid) listing the Canadian Living credit in my cover letter. They said, "Oh look. A Canadian. How quaint. See how she spells humour." (I'm paraphrasing.) Anyways, Star published several of my short shorts in the 90s. The Canadian Living credit got me in the door.

With several Star Mag credits under my belt (weird term, that - I mean, think of what is under your belt) I went to Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine. They liked the Star credits and published some of my stories. Then I got a several-story contract with ComputorEdge.

So ten years ago, when I had a novel to flog, I already had 24 short story publications in commercial magazines. That set me apart from everyone else clawing to get in the door.

Writing for magazines worked to launch my author career. I'm now with two traditional publishers and my 11th book (The Bootlegger's Goddaughter - phew! Got that in) comes out in February.

Writing for magazines tells a publisher several things:

1. You write commercially salable stories. This is important for book publishers. If you have published in commercial magazines, it tells a publisher that someone else has already paid you for your fiction. They deemed your obviously brilliant stores worthy of a wide enough audience to justify putting their money into publishing them. It's much like the concept of 'peer review' in the academic world.

2. You accept editing. A magazine writer (fiction or nonfiction) is used to an editor making changes to their work. It's part of the game. If you have been published many times in magazines, then a novel publisher knows you are probably going to be cool with editing. (Okay, maybe not cool, but you've learned how to hold back rage-fueled comments such as "Gob-sucking fecking idiot! It was perfect before you mucked with it."

3. You work to deadline. Magazines and newspapers have tight deadlines. Miss your deadline, and you're toast. Novel publishers are similarly addicted to deadlines. Something to do with having booked a print run long in advance, for one thing. So they want authors who will get their damned manuscripts in on time.

Here's something to watch out for if you are going to write for magazines:

Kill Fee

If you are publishing with a major magazine, negotiate a 'kill fee.' (This doesn't mean you get to kill the publisher if they don't print your story.) A kill fee is something you get if the mag sends you a contract to publish your story or article, and then doesn't publish it. Usually a kill fee is about half the amount you would be paid if they had printed it.

Why wouldn't they print your story after they agree to buy it? Sometimes a publisher or editorial big wig leaves and the new big wig taking over will have a different vision for the mag. Sometimes a mag will go under before they actually print the issue with your story. That happened to me with a fairly well-known women's mag. I got the kill fee, and the rights back. I was able to sell the story to another magazine.

Which brings me to a final point: Note the rights you are selling. Many mags here want "First North American Serial Rights." This means they have the right to publish the story for the first time in North America, in all versions of their magazine. (For instance, some magazines in Canada publish both English and French versions.) But what happens after that? When do rights return to you? Two years after publication? (Very common.) Or never? Are they buying 'All Rights?" It's good to get rights back, because then you can have the story reprinted in an anthology someday. Make sure your contract stipulates which rights they are buying.

Of course, I always say, if they pay me enough, they can keep all rights, dress them in furs and jewelry, and walk them down Main Street. I have the same attitude re film companies that might want to swoop up my novels for movies.

Melodie Campbell writes the multi-award-winning Goddaughter series of mob comedies, starting with The Goddaughter. It features a different kind of 'kill fee.'

On Amazon

Showing posts with label short stories. Show all posts

Showing posts with label short stories. Show all posts

26 November 2016

Want Street Cred? Write for Magazines!

Labels:

Alfred Hitchcock,

Canada,

crime,

fiction,

magazines,

Melodie Campbell,

mystery magazine,

novels,

short stories,

writing

12 November 2016

Camouflaging Clues

by Unknown

by B.K. Stevens

"The grandest game in the world"--that's how Edward D. Hoch describes the duel between mystery writer and mystery reader. In an essay called "The Pleasure of the Short Story," Hoch explains why he prefers mysteries "in which the reader is given a clue or hint well in advance of the ending. As a reader myself I find the greatest satisfaction in spotting the clue and anticipating the author. If I overlook it, I don't feel cheated--I admire the author's skill!"*

And it takes a lot of skill. In any mystery where this "grandest game" is played, the delightful challenge offered to readers poses daunting challenges for writers. We have to provide readers with clues "well in advance of the ending," as Hoch says. In my opinion (and I bet Hoch would agree), we should provide plenty of clues, and they should start as soon as possible. As a reader, I feel a tad frustrated by mysteries that hinge on a single clue--if we don't pick up on a quick reference indicating the killer was wearing gloves on a warm day, we have no chance of figuring things out. I also don't much enjoy mysteries that look like whodunits but are really just histories of investigations.

The detective questions A, who provides a scrap of information pointing to B, who suggests talking to C. Finally, somewhere around F, the detective happens upon the only truly relevant clue, which leads straight to a solution that's obvious now but would have been impossible to guess even three minutes sooner. That's not much fun.

But working in lots of clues throughout the mystery isn't easy. Hoch identifies "the great clue bugaboo" that plagues many detective stories: "Clues are inserted with such a heavy hand that they almost scream their presence at the reader." Especially in short stories, Hoch says, avoiding that bugaboo requires "a great deal of finesse." I think that's true not only in whodunits but also in mysteries that build suspense by hinting at endings alert readers have a fair chance of predicting before they reach the last page. Luckily, there are ways of camouflaging clues, of hiding them in plain sight so most readers will overlook them.

Here are five camouflage techniques--you've probably used some or all of them yourself. Since it wouldn't be polite to reveal other writers' clues, I'll illustrate the descriptions with examples from my own stories.That way, if I give away too much and spoil the stories, the only person who can get mad at me is me. (By some strange coincidence, all the stories I'll mention happen to be in my recent collection from Wildside Press, Her Infinite Variety: Tales of Women and Crime.)

Sneak clues in before readers expect them: Readers expect the beginning of a mystery to intrigue them and provide crucial back story--or, perhaps, to plunge them into the middle of action. They don't necessarily expect to be slapped in the face with clues right away. So if we slide a clue into our opening sentences, it might go unnoticed. That's what I tried to do in "Aunt Jessica's Party," which first appeared in Woman's World in 1993. It's not a whodunit, but the protagonist's carrying out a scheme, and readers can spot it if they pay attention. Here's how the story begins:

Hide a clue in a series of insignificant details: If a detective searches a crime scene and finds an important clue--an oil-stained rag, say--we're obliged to tell readers. But if we don't want to call too much attention to the clue, we can hide it in a list of other things the detective finds, making sure some sound as intriguing as an oil-stained rag. I used this technique in "Death in Rehab," a whodunit published in Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine in 2011. When temporary secretary Leah Abrams accepts a job at a rehab center, her husband, Sam, doesn't like the idea that she'll be "surrounded by addicts." Leah counters that being around recovering addicts will be inspirational, not dangerous, but Sam's not convinced:

Separate clues from context: We're obliged to provide the reader with clues and also, I think, to provide the context needed to interpret them. But I don't think we're obliged to provide both at the same time. By putting a careful distance between clue and context, we can play fair and still keep the reader guessing. In "The Shopper," a whodunit first published in a 2014 convention anthology, a young librarian's house is burglarized while she's at home, asleep. That's unsettling enough, but her real worries begin when the burglar--a pro the police have nicknamed The Shopper--starts sending her notes and returning some things he stole. He seems obsessed with her. Also, two men she's never seen before--one blond, one dark--start showing up at the library every day. She suspects one of them might be The Shopper, but which one? (And who says you can't have a puzzling whodunit with only two suspects?) Then things get worse:

Use the protagonist's point of view to mislead readers: This technique isn't reserved for mystery writers. In "Emma Considered as Detective Fiction," P.D. James comments on Jane Austen's skillful manipulation of point of view to conceal the mysteries at the heart of her novel. Emma constantly misinterprets what people do and say, and because we readers see things from Emma's perspective, we're equally oblivious to what's really going on. In our own mysteries, unless our protagonist is a genius who instantly understands everything, we can use the same technique: If our protagonist overlooks clues, chances are readers will overlook them, too. In "A Joy Forever" (AHMM, 2015), photographer Chris is visiting Uncle Mike and his second wife, Gwen. Uncle Mike is a tyrant who's reduced Gwen to the status of domestic slave--he orders her around, never helps her, casually insults her. Gwen takes it all without a murmur. After a dinner during which Uncle Mike behaves even more boorishly than usual, Chris follows Gwen to the kitchen to help with the dishes:

Distract readers with action or humor: If readers get caught up in an action scene, they may forget they're supposed to be watching for clues; if they're chuckling at a character's dilemma, they may not notice puzzle pieces slipping by. In "Table for None" (AHMM, 2008), apprentice private detective Harriet Russo is having a rough night. She's on a dark, isolated street, staking out a suspect. But he spots her, threatens her, and stalks off. Moments later, her client, Little Dave, pops up unexpectedly and proposes searching the suspect's car. Harriet says it's too dangerous, but Little Dave won't listen:

We can also distract readers with clever dialogue, with fascinating characters, with penetrating social satire, with absorbing themes, with keen insights into human nature. In the end, excellent writing is the best way to keep readers from focusing only on the clues we parade past them. Of course, that's not our main reason for trying to make our writing excellent. To use Hoch's phrase again, mysteries invite writers and readers to participate in "the grandest game," but that doesn't mean mysteries are no more than a game. I think mysteries can be as compelling and significant as other kinds of fiction. The grandest game doesn't impose limits on what our stories and novels can achieve. It simply adds another element that I and millions of other readers happen to enjoy.

Do you have favorite ways of camouflaging clues? I'd love to see some examples from your own mysteries. (*Hoch's essay, by the way, is in the Mystery Writers of America Mystery Writer's Handbook, edited by Lawrence Treat, published in 1976, revised and reprinted several times since then. Used copies are available through Amazon.)

"The grandest game in the world"--that's how Edward D. Hoch describes the duel between mystery writer and mystery reader. In an essay called "The Pleasure of the Short Story," Hoch explains why he prefers mysteries "in which the reader is given a clue or hint well in advance of the ending. As a reader myself I find the greatest satisfaction in spotting the clue and anticipating the author. If I overlook it, I don't feel cheated--I admire the author's skill!"*

And it takes a lot of skill. In any mystery where this "grandest game" is played, the delightful challenge offered to readers poses daunting challenges for writers. We have to provide readers with clues "well in advance of the ending," as Hoch says. In my opinion (and I bet Hoch would agree), we should provide plenty of clues, and they should start as soon as possible. As a reader, I feel a tad frustrated by mysteries that hinge on a single clue--if we don't pick up on a quick reference indicating the killer was wearing gloves on a warm day, we have no chance of figuring things out. I also don't much enjoy mysteries that look like whodunits but are really just histories of investigations.

The detective questions A, who provides a scrap of information pointing to B, who suggests talking to C. Finally, somewhere around F, the detective happens upon the only truly relevant clue, which leads straight to a solution that's obvious now but would have been impossible to guess even three minutes sooner. That's not much fun.

But working in lots of clues throughout the mystery isn't easy. Hoch identifies "the great clue bugaboo" that plagues many detective stories: "Clues are inserted with such a heavy hand that they almost scream their presence at the reader." Especially in short stories, Hoch says, avoiding that bugaboo requires "a great deal of finesse." I think that's true not only in whodunits but also in mysteries that build suspense by hinting at endings alert readers have a fair chance of predicting before they reach the last page. Luckily, there are ways of camouflaging clues, of hiding them in plain sight so most readers will overlook them.

Here are five camouflage techniques--you've probably used some or all of them yourself. Since it wouldn't be polite to reveal other writers' clues, I'll illustrate the descriptions with examples from my own stories.That way, if I give away too much and spoil the stories, the only person who can get mad at me is me. (By some strange coincidence, all the stories I'll mention happen to be in my recent collection from Wildside Press, Her Infinite Variety: Tales of Women and Crime.)

Sneak clues in before readers expect them: Readers expect the beginning of a mystery to intrigue them and provide crucial back story--or, perhaps, to plunge them into the middle of action. They don't necessarily expect to be slapped in the face with clues right away. So if we slide a clue into our opening sentences, it might go unnoticed. That's what I tried to do in "Aunt Jessica's Party," which first appeared in Woman's World in 1993. It's not a whodunit, but the protagonist's carrying out a scheme, and readers can spot it if they pay attention. Here's how the story begins:

Carefully, Jessica polished her favorite sherry glass and placed it on the silver tray. Soon, her nephew would arrive. He was to be the only guest at her little party, and everything had to be perfect.I count at least six facts relevant to the story's solution in these paragraphs; even Jessica's pause is significant. And there's one solid clue, an oddity that should make readers wonder. Jessica's planned the timing of this call ("time to call Grace"), but why call only five minutes before her nephew's scheduled to arrive? She can't be calling to chat--what other purpose might the call serve? I'm hoping that readers won't notice the strange timing, that they'll focus instead on hints about Jessica's relationship with her nephew and the "special present" she's giving him. I've played fair by providing a major clue. If readers aren't ready for it, it's not my fault.

Five minutes until six--time to call Grace. She went to the phone near the kitchen window, kept her eyes on the driveway, and dialed.

"Hello, Grace?" she said. "Jessica. How are you? Oh, I'm fine--never better. Did I tell you William's coming today? Yes, it is an accomplishment to get him here. But it's his birthday, and I promised him a special present. He even agreed to pick up some sherry for me. Oh, there he is, pulling into the driveway." She paused. "Goodbye, Grace. You're a dear."

Hide a clue in a series of insignificant details: If a detective searches a crime scene and finds an important clue--an oil-stained rag, say--we're obliged to tell readers. But if we don't want to call too much attention to the clue, we can hide it in a list of other things the detective finds, making sure some sound as intriguing as an oil-stained rag. I used this technique in "Death in Rehab," a whodunit published in Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine in 2011. When temporary secretary Leah Abrams accepts a job at a rehab center, her husband, Sam, doesn't like the idea that she'll be "surrounded by addicts." Leah counters that being around recovering addicts will be inspirational, not dangerous, but Sam's not convinced:

"They're still addicts, and addicts do dangerous things. Did you read the local news this morning?" He found the right page and pointed to a headline. "'Gambling Addict Embezzles Millions, Disappears'--probably in Vegas by now, the paper says. Or this story--`Small-time Drug Dealer Killed Execution Style'--probably because he stole from his bosses, the paper says. Or this one--`Shooter Flies into Drunken Rage, Wounds Two'--the police haven't caught that one, either."Savvy mystery readers may suspect one of these news stories will be relevant to the mystery, but they can't yet know which one (this is another early-in-the-story clue). In fact, I've tried to make the two irrelevant headlines sound more promising than the one that actually matters--and if you decide to read the story, that's a big extra hint for you. About halfway through the story, Sam mentions the three news stories again. By now, readers who have paid attention to all the clues provided during Leah's first day at work should have a good sense of which story is relevant. But I don't think most readers will figure out murderer and motive yet--and if they do, I don't much care. I've packed this story so full of clues that I doubt many readers will spot all of them. Even readers who realize whodunit should find some surprises at the end.

Separate clues from context: We're obliged to provide the reader with clues and also, I think, to provide the context needed to interpret them. But I don't think we're obliged to provide both at the same time. By putting a careful distance between clue and context, we can play fair and still keep the reader guessing. In "The Shopper," a whodunit first published in a 2014 convention anthology, a young librarian's house is burglarized while she's at home, asleep. That's unsettling enough, but her real worries begin when the burglar--a pro the police have nicknamed The Shopper--starts sending her notes and returning some things he stole. He seems obsessed with her. Also, two men she's never seen before--one blond, one dark--start showing up at the library every day. She suspects one of them might be The Shopper, but which one? (And who says you can't have a puzzling whodunit with only two suspects?) Then things get worse:

I'd say there are five major clues in this story. Two are contained--or, in one case, reinforced--in these paragraphs. A reader keeping careful track of all the evidence could identify The Shopper right now, without reading the remaining seven pages. But since these clues are revealing only in the context of information provided five pages earlier, I'm betting most readers won't make the connection. The Shopper's secrets are still safe with me.

She didn't really feel like going out that night, but she and Lori had a long-standing date for dinner and a movie. It'd be embarrassing to admit she was scared to go out, and the company would do her good. But when she got to the restaurant, she spotted the blond man sitting in a booth, eating a slab of pie. He has a right to eat wherever he wants, she thought; but the minute Lori arrived, Diane grabbed her hand, pulled her to a table at the other end of the restaurant, and sighed with relief when the blond man left after a second cup of coffee.

The relief didn't last long. As she and Lori walked out, she saw the dark man sitting at the counter, picking at a salad. He must have come in after she had--had he followed her? She couldn't stand it any more.

Use the protagonist's point of view to mislead readers: This technique isn't reserved for mystery writers. In "Emma Considered as Detective Fiction," P.D. James comments on Jane Austen's skillful manipulation of point of view to conceal the mysteries at the heart of her novel. Emma constantly misinterprets what people do and say, and because we readers see things from Emma's perspective, we're equally oblivious to what's really going on. In our own mysteries, unless our protagonist is a genius who instantly understands everything, we can use the same technique: If our protagonist overlooks clues, chances are readers will overlook them, too. In "A Joy Forever" (AHMM, 2015), photographer Chris is visiting Uncle Mike and his second wife, Gwen. Uncle Mike is a tyrant who's reduced Gwen to the status of domestic slave--he orders her around, never helps her, casually insults her. Gwen takes it all without a murmur. After a dinner during which Uncle Mike behaves even more boorishly than usual, Chris follows Gwen to the kitchen to help with the dishes:

As I watched her standing at the sink, sympathy overpowered me again. She was barely fifty but looked like an old woman--bent, scrawny, exhausted, her graying hair pulled back in a tight bun. And her drab, shapeless dress had to be at least a decade old.Chris sees Gwen as a victim, as a woman whose spirit has been utterly crushed by an oppressor. Readers who don't see beyond Chris's perspective have some surprises coming. But in this story, by this point, I think most readers will see more than Chris does. They'll pick up on clues such as Gwen's hard smile, her quiet "not yet." I had fun playing with point of view in this story, with giving alert readers plenty of opportunities to stay one step ahead of the narrator. It's another variation on Hoch's "grandest game."

"You spend so much on Uncle Mike," I chided. "The golf cart, all that food and liquor. Spend something on yourself. Go to a beauty parlor and have your hair cut and styled. Buy yourself some new clothes."

She laughed softly. "Oh, Mike really needs what I buy for him--he really, really does. And I don't care how my hair looks, and I don't need new clothes." Her smile hardened. "Not yet."

I felt so moved, and so sorry, that I leaned over and kissed the top of her head. "You're too good to him."

Distract readers with action or humor: If readers get caught up in an action scene, they may forget they're supposed to be watching for clues; if they're chuckling at a character's dilemma, they may not notice puzzle pieces slipping by. In "Table for None" (AHMM, 2008), apprentice private detective Harriet Russo is having a rough night. She's on a dark, isolated street, staking out a suspect. But he spots her, threatens her, and stalks off. Moments later, her client, Little Dave, pops up unexpectedly and proposes searching the suspect's car. Harriet says it's too dangerous, but Little Dave won't listen:

I hope readers will focus on the conflict and confusion in this scene, and on the unseen attack that leaves Harriet in bad shape and Little Dave in worse shape. I hope they won't pause to take careful note of exactly what Little Dave says in his phone conversation, to test it against the way he's behaved earlier and the things people say later. If readers are too focused on the action to pick up on inconsistencies, they'll miss evidence that could help them identify the murderer.

He raced off. For a moment, I stood frozen. Call Miss Woodhouse and tell her how I'd botched things--let Little Dave get himself killed and feel guilty for the rest of my life--follow him into the parking lot and risk getting killed myself. On the whole, the last option seemed most attractive. I raced after Little Dave.

He stood next to the dirty white car, hissing into his cell phone. "Damn it, Terry," he whispered harshly, "I told you not to call me. No, I won't tell you where I am. Just go home. I'll see ya when I see ya." He snapped his phone shut and yanked on a back door of the car. It didn't budge. He looked straight at me, grinning sheepishly.

That's pretty much the last thing I remember. I have some vague impression of something crashing down against me, of sharp pain and sudden darkness. But my next definite memory is of fading slowly back into consciousness--of hearing sirens blare, of feeling the cement against my back, of seeing Little Dave sprawled a few feet away from me, of spotting a small iron figurine next to him, of falling into darkness again.

We can also distract readers with clever dialogue, with fascinating characters, with penetrating social satire, with absorbing themes, with keen insights into human nature. In the end, excellent writing is the best way to keep readers from focusing only on the clues we parade past them. Of course, that's not our main reason for trying to make our writing excellent. To use Hoch's phrase again, mysteries invite writers and readers to participate in "the grandest game," but that doesn't mean mysteries are no more than a game. I think mysteries can be as compelling and significant as other kinds of fiction. The grandest game doesn't impose limits on what our stories and novels can achieve. It simply adds another element that I and millions of other readers happen to enjoy.

Do you have favorite ways of camouflaging clues? I'd love to see some examples from your own mysteries. (*Hoch's essay, by the way, is in the Mystery Writers of America Mystery Writer's Handbook, edited by Lawrence Treat, published in 1976, revised and reprinted several times since then. Used copies are available through Amazon.)

22 October 2016

Passport to Murder! Announcing...the Bouchercon 2017 Anthology Competition

First, a bit about Destination:TORONTO

Toronto the Good

Hogtown

The Big Smoke

Toronto has had a lot of nicknames, but I like this description best:

Toronto is “New York run by the Swiss.” (Peter Ustinov, 1987)

He meant that in a good way, of course! Toronto is a big city - the Greater Toronto Area is more than 6 million. Our restaurant scene is second to none. We may be the most diverse city in the world. How great is our diversity? When I worked in health care, our government agency had 105 dialects spoken by staff!

It's my great pleasure to be part of the Bouchercon 2017 Committee. Many of you know my friends Helen Nelson and Janet Costello, who are the conference co-chairs. With these gals in charge, you know it will be an unforgettable conference. Come to our town, for a great Crime Time!

You can check all the details here: www.bouchercon2017.com

Even if you aren't registered for Bouchercon 2017, you can still enter the anthology competition!

Our theme is the convention theme—Passport to Murder—so include a travel theme with actual travel or the desire to travel with or without passports. And it must include at least a strong suggestion of murder or a plan to commit murder…. All crime sub-genres welcome.

Publication date: October 12, 2017.

Editor: John McFetridge

Publisher: Down & Out Books

All stories, by all authors, will be donated to the anthology as part of the overall donation to our literacy charity fundraising efforts. All profits on the anthology (including those of the publisher) will be donated to our charity.

Guests of Honour for Bouchercon 2017 will be invited to contribute to the anthology. For open submissions, preliminary selection for publication will be blind, by a panel of three judges, with final, blind selection by the editor.

The details:

Toronto the Good

Hogtown

The Big Smoke

Toronto has had a lot of nicknames, but I like this description best:

Toronto is “New York run by the Swiss.” (Peter Ustinov, 1987)

He meant that in a good way, of course! Toronto is a big city - the Greater Toronto Area is more than 6 million. Our restaurant scene is second to none. We may be the most diverse city in the world. How great is our diversity? When I worked in health care, our government agency had 105 dialects spoken by staff!

It's my great pleasure to be part of the Bouchercon 2017 Committee. Many of you know my friends Helen Nelson and Janet Costello, who are the conference co-chairs. With these gals in charge, you know it will be an unforgettable conference. Come to our town, for a great Crime Time!

You can check all the details here: www.bouchercon2017.com

DRUM ROLL...... announcing PASSPORT TO MURDER,

the Bouchercon 2017 Anthology

Even if you aren't registered for Bouchercon 2017, you can still enter the anthology competition!

Our theme is the convention theme—Passport to Murder—so include a travel theme with actual travel or the desire to travel with or without passports. And it must include at least a strong suggestion of murder or a plan to commit murder…. All crime sub-genres welcome.

Publication date: October 12, 2017.

Editor: John McFetridge

Publisher: Down & Out Books

All stories, by all authors, will be donated to the anthology as part of the overall donation to our literacy charity fundraising efforts. All profits on the anthology (including those of the publisher) will be donated to our charity.

Guests of Honour for Bouchercon 2017 will be invited to contribute to the anthology. For open submissions, preliminary selection for publication will be blind, by a panel of three judges, with final, blind selection by the editor.

The details:

- The story must include travel and at least a strong suggestion of murder or a plot to commit murder.

- Story length: a maximum of 5000 words

- Electronic submissions only.

- RTF format, preferably double-spaced

- Times New Roman or similar font (12 point)

- Paragraph indent .5 inch (or 1.25 cm). Please do not use tabs or space bar.

- Include story title and page number in document header.

- Maximum of one entry per author

- Open to both writers who have been previously published, in any format, and those who have never been published.

- The story must be previously unpublished in ANY format, electronic or print.

- Please remove your name or any identifying marks from your story. Any story that can be associated with the author will either be returned for correction (if there is time) or disqualified.

- Please include a brief bio in your submission form (max 150 words) and NOT in the body of your story.

- After Bouchercon 2017 and Down & Out Books expenses have been recovered, all proceeds will be donated to Bouchercon 2017’s literacy charity of choice.

- Copyright will remain with the authors.

- Authors must be prepared to sign a contract with Down & Out Books.

- Submissions must be e-mailed no later than 11:59 P.M (EST) January 31, 2017. Check the website (www.bouchercon2017.com) for full details and entry form.

Labels:

anthologies,

Bouchercon,

conferences,

crime fiction,

crimes,

short stories,

Toronto

16 August 2016

Shannon and Jess Get Short with Readers

by Barb Goffman

by Shannon Baker and Jessica Lourey

Thanks, Barb Goffman, for giving up her blogging spot so Shannon Baker and I can visit, and thanks to SleuthSayers for this warm welcome! We brought popcorn and root beer floats but don’t know if there is enough to go around, so raise your hand quick if you’re hungry/thirsty.

Whee! See all those hands, Shannon? You pass out the treats while I handle the intros.

Whee! See all those hands, Shannon? You pass out the treats while I handle the intros.

The beautiful Shannon and I are on a whirlwind 25-stop blog tour, an idea that seemed genius when we realized our next books both release on September 6. Shannon’s is Stripped Bare. It’s been called Longmire meets The Good Wife and is about a woman sheriff in the Nebraska Sandhills. My book is Salem’s Cipher, a breakneck thriller about a race to save the first viable U.S. female presidential candidate from assassination. Both books are available for preorder.

Today, we’d like to talk about short stories, primarily because Barb is an Agatha Award-winning short story WIZARD, and so this is sort of a gift to her. Except not really, because Shannon and I blow at writing short stories. So, it’s either an un-gift in that we could never match Barb’s insight, or a huge gift because we’ll have set the bar so low that you’ll clamor for Barb’s return, even if she doesn’t bring the ice cream like we do.

Shannon here, adding her two cents: While Barb is undoubtedly the queen, don’t believe Jess when she says she’s not great at short stories. For a treat, grab hold of her Death by Potato Salad, Murder by the Minute. You WILL laugh.

Shannon, you vixen, sneaking in the kind words like that. Thank you. Now tell me,

what’s the first short story you ever published?

Shannon: The Phoenix chapter of Sisters in Crime, Desert Sleuths, periodically publishes an anthology and were kind enough to take on my first short story in SoWest: Desert Justice. It combined my love of the Grand Canyon and my delight at killing off lousy men. It’s roughly based on a 9-day river trip I convinced my non-lousy husband to paddle with me. Hiking, riding rapids, jumping into waterfalls, all the good stuff. He loves an exciting adventure, but has some claustrophobia and a mild fear of heights (despite being a pilot). At one point, lying with a damp sheet over us because the nights were so incredibly hot, he turned to me and sweetly said, “This is like a fucking Outward Bound trip.” Ah, good times.

Jess here. Shannon, you make me laugh. And want to take river

trips, weirdly. Okay, my first published short story was “The Locked

Fish-cleaning Room Mystery.” Snappy, yes? I wrote it at the request of a

group of Minnesota crime writers, William Kent Krueger among them, who

were putting together an anthology called Resort to Murder. When I was

asked to contribute, I said yes. I figured I could write novels, so why

not short stories?

Folks, that’s like figuring you can paint a house, so why not carve the Taj Mahal on a piece of rice. I failed miserably and repeatedly until I decided to research classic crime fiction shorts. I stumbled across the locked room mystery (a la Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Murders at the Rue Morgue”) and fell in love with its neat and sweet format. I strapped a Minnesota setting onto that structure, and voila!

Shannon, do you have a technique when it comes to writing short stories?

Shannon: No. Hell no. I wish I did. I’m going to try your method, whatever it is, because we’re both giving away shorts if readers preorder our books. I haven’t written mine, yet. I get hives thinking about it. What’s your best advice on this?

Jess again. I wish I had a technique. I write short stories like a kid runs down a hill: poorly, hoping not to fall on my face. I am exploring novellas right now, though, because there are two books left in my humorous Murder-by-Month series, and my agent and my publisher are taking forever to figure out that contract. I miss the characters in the series, and it turns out that I am free to write about them in a novella form. How fun is that? I think novellas might be a growing self-pub market.

What do you think about self-pubbing, Shannon, whether short story, novella, or novel?

Shannon: (whining) Why are you asking me the hard questions? Yes, sure. I’d love to self pub. But I’d have to write something first, wouldn’t I? The not so secret thing about me is that I’m really lazy. Right now, I’m working hard on the Kate Fox series and happily letting a publisher figure out the cover, distribution, and production side.

That’s it today with lazy Shannon (my favorite piece of furniture) and Hard-Question-Asking Jessie. Stick with us on our road trip as we head to Word Nerds tomorrow for a little friendly banter and a writing tip or two. We promise to make a potty stop along the way if you need it.

Share your favorite short story writing tip (god, please), or leave a comment below for a chance to win an advance copy of Salem’s Cipher or Stripped Bare.

And for even more fun:

If you order Salem's Cipher before September 6, 2016, you are invited to forward your receipt to salemscipher@gmail.com to receive a Salem short story and to be automatically entered in a drawing to win a 50-book gift basket mailed to the winner's home!

If you order Stripped Bare before September 6, 2016, you are invited to forward your receipt to katefoxstrippedbare@gmail.com to receive a Kate Fox short story and be entered for a book gift basket mailed to your home.

You’re welcome to preorder each to enter each contest.

Jessica (Jess) Lourey is best known for her critically acclaimed

Murder-by-Month mysteries, which have earned multiple starred reviews

from Library Journal and Booklist, the latter calling her writing "a

splendid mix of humor and suspense." She is a tenured professor of

creative writing and sociology, a recipient of The Loft's 2014

Excellence in Teaching fellowship, and leads interactive writing

workshops all over the world. Salem’s Cipher, the first in her thrilling

Witch Hunt Series, hits stores September 2016. You can find out more at

www.jessicalourey.com, or find Jess on Facebook or Twitter.

Jessica (Jess) Lourey is best known for her critically acclaimed

Murder-by-Month mysteries, which have earned multiple starred reviews

from Library Journal and Booklist, the latter calling her writing "a

splendid mix of humor and suspense." She is a tenured professor of

creative writing and sociology, a recipient of The Loft's 2014

Excellence in Teaching fellowship, and leads interactive writing

workshops all over the world. Salem’s Cipher, the first in her thrilling

Witch Hunt Series, hits stores September 2016. You can find out more at

www.jessicalourey.com, or find Jess on Facebook or Twitter.

Shannon Baker is the author of the Nora Abbott mystery series from Midnight Ink, a fast-paced mix of Hopi Indian mysticism, environmental issues, and murder set in western landscapes of Flagstaff, AZ, Boulder, CO, and Moab, UT. Seconds before quitting writing forever and taking up competitive drinking, Shannon was nominated for Rocky Mountain Fiction Writer’s 2014 Writer of the Year. Buoyed with that confidence, she acquired an agent who secured a multi-book contract with Tor/Forge. The first in the Kate Fox Mystery Series, Stripped Bare, will release in hardcover September 2016. Set in the isolated cattle country of the Nebraska Sandhills, it’s been called Longmire meets The Good Wife. Visit Shannon at www.Shannon-Baker.com.

Thanks, Barb Goffman, for giving up her blogging spot so Shannon Baker and I can visit, and thanks to SleuthSayers for this warm welcome! We brought popcorn and root beer floats but don’t know if there is enough to go around, so raise your hand quick if you’re hungry/thirsty.

Whee! See all those hands, Shannon? You pass out the treats while I handle the intros.

Whee! See all those hands, Shannon? You pass out the treats while I handle the intros.The beautiful Shannon and I are on a whirlwind 25-stop blog tour, an idea that seemed genius when we realized our next books both release on September 6. Shannon’s is Stripped Bare. It’s been called Longmire meets The Good Wife and is about a woman sheriff in the Nebraska Sandhills. My book is Salem’s Cipher, a breakneck thriller about a race to save the first viable U.S. female presidential candidate from assassination. Both books are available for preorder.

Today, we’d like to talk about short stories, primarily because Barb is an Agatha Award-winning short story WIZARD, and so this is sort of a gift to her. Except not really, because Shannon and I blow at writing short stories. So, it’s either an un-gift in that we could never match Barb’s insight, or a huge gift because we’ll have set the bar so low that you’ll clamor for Barb’s return, even if she doesn’t bring the ice cream like we do.

Shannon here, adding her two cents: While Barb is undoubtedly the queen, don’t believe Jess when she says she’s not great at short stories. For a treat, grab hold of her Death by Potato Salad, Murder by the Minute. You WILL laugh.

|

| These chips aren't in the story. They're just funny. |

Shannon: The Phoenix chapter of Sisters in Crime, Desert Sleuths, periodically publishes an anthology and were kind enough to take on my first short story in SoWest: Desert Justice. It combined my love of the Grand Canyon and my delight at killing off lousy men. It’s roughly based on a 9-day river trip I convinced my non-lousy husband to paddle with me. Hiking, riding rapids, jumping into waterfalls, all the good stuff. He loves an exciting adventure, but has some claustrophobia and a mild fear of heights (despite being a pilot). At one point, lying with a damp sheet over us because the nights were so incredibly hot, he turned to me and sweetly said, “This is like a fucking Outward Bound trip.” Ah, good times.

|

| Not Shannon. |

Folks, that’s like figuring you can paint a house, so why not carve the Taj Mahal on a piece of rice. I failed miserably and repeatedly until I decided to research classic crime fiction shorts. I stumbled across the locked room mystery (a la Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Murders at the Rue Morgue”) and fell in love with its neat and sweet format. I strapped a Minnesota setting onto that structure, and voila!

Shannon, do you have a technique when it comes to writing short stories?

Shannon: No. Hell no. I wish I did. I’m going to try your method, whatever it is, because we’re both giving away shorts if readers preorder our books. I haven’t written mine, yet. I get hives thinking about it. What’s your best advice on this?

Jess again. I wish I had a technique. I write short stories like a kid runs down a hill: poorly, hoping not to fall on my face. I am exploring novellas right now, though, because there are two books left in my humorous Murder-by-Month series, and my agent and my publisher are taking forever to figure out that contract. I miss the characters in the series, and it turns out that I am free to write about them in a novella form. How fun is that? I think novellas might be a growing self-pub market.

|

| Not a kid but still funny. |

What do you think about self-pubbing, Shannon, whether short story, novella, or novel?

Shannon: (whining) Why are you asking me the hard questions? Yes, sure. I’d love to self pub. But I’d have to write something first, wouldn’t I? The not so secret thing about me is that I’m really lazy. Right now, I’m working hard on the Kate Fox series and happily letting a publisher figure out the cover, distribution, and production side.

That’s it today with lazy Shannon (my favorite piece of furniture) and Hard-Question-Asking Jessie. Stick with us on our road trip as we head to Word Nerds tomorrow for a little friendly banter and a writing tip or two. We promise to make a potty stop along the way if you need it.

Share your favorite short story writing tip (god, please), or leave a comment below for a chance to win an advance copy of Salem’s Cipher or Stripped Bare.

|

| Not these kind of tips! |

If you order Salem's Cipher before September 6, 2016, you are invited to forward your receipt to salemscipher@gmail.com to receive a Salem short story and to be automatically entered in a drawing to win a 50-book gift basket mailed to the winner's home!

If you order Stripped Bare before September 6, 2016, you are invited to forward your receipt to katefoxstrippedbare@gmail.com to receive a Kate Fox short story and be entered for a book gift basket mailed to your home.

You’re welcome to preorder each to enter each contest.

Jessica (Jess) Lourey is best known for her critically acclaimed

Murder-by-Month mysteries, which have earned multiple starred reviews

from Library Journal and Booklist, the latter calling her writing "a

splendid mix of humor and suspense." She is a tenured professor of

creative writing and sociology, a recipient of The Loft's 2014

Excellence in Teaching fellowship, and leads interactive writing

workshops all over the world. Salem’s Cipher, the first in her thrilling

Witch Hunt Series, hits stores September 2016. You can find out more at

www.jessicalourey.com, or find Jess on Facebook or Twitter.

Jessica (Jess) Lourey is best known for her critically acclaimed

Murder-by-Month mysteries, which have earned multiple starred reviews

from Library Journal and Booklist, the latter calling her writing "a

splendid mix of humor and suspense." She is a tenured professor of

creative writing and sociology, a recipient of The Loft's 2014

Excellence in Teaching fellowship, and leads interactive writing

workshops all over the world. Salem’s Cipher, the first in her thrilling

Witch Hunt Series, hits stores September 2016. You can find out more at

www.jessicalourey.com, or find Jess on Facebook or Twitter.Shannon Baker is the author of the Nora Abbott mystery series from Midnight Ink, a fast-paced mix of Hopi Indian mysticism, environmental issues, and murder set in western landscapes of Flagstaff, AZ, Boulder, CO, and Moab, UT. Seconds before quitting writing forever and taking up competitive drinking, Shannon was nominated for Rocky Mountain Fiction Writer’s 2014 Writer of the Year. Buoyed with that confidence, she acquired an agent who secured a multi-book contract with Tor/Forge. The first in the Kate Fox Mystery Series, Stripped Bare, will release in hardcover September 2016. Set in the isolated cattle country of the Nebraska Sandhills, it’s been called Longmire meets The Good Wife. Visit Shannon at www.Shannon-Baker.com.

Labels:

Barb Goffman,

Jess Lourey,

Shannon Baker,

short stories

16 July 2016

I Like Short Shorts

by John Floyd

Two weeks ago, I was sitting in a rocker on the back porch of a beach house on Perdido Key, with sand in my shoes and "Margaritaville" on my mind. In fact I was half-dozing to the soothing sound of the incoming waves when I also heard the DING of an incoming text message. This was the sixth day of our annual family getaway, but since we never completely get away from technology I dutifully dug my cell phone out of my pocket, checked the message (from one of our kids, a hundred yards up the beach), and replied to it. I also decided to check my emails, which I hadn't done in a while. I was glad I did. At the top of the list was a note that had only just arrived, informing me of the acceptance of my 80th story in Woman's World magazine. Not a particularly round number or notable milestone, I guess, but I'll tell you, it made my day. It also reminded me how fortunate I am--a southern guy raised on cop shows and Westerns, who in school liked math and science far better than English--to have sold that many stories to, of all places, a weekly women's magazine based in New Jersey.

WW, as some of you know, has been around a long time. What makes it appealing to writers of short stories is that it features a mystery and a romance in every issue, it pays well, and it has a circulation of 8.5 million. Since I'm obviously more at ease with mysteries than romances, most of my stories for that publication have been in the mystery genre. I've managed to sell them a couple of romances too, but the truth is, I'm the great pretender: my romance stories were actually little twisty adventures that involved more deception than anything else.

Figures and statistics

Although I've been writing stories for Woman's World for seventeen years now, 50 of those 80 sales have happened since 2010, and I think that's because I have gradually become more comfortable with the task of telling a complete story in less than a thousand words--what some refer to as a short short. (At WW, the max wordcount for mysteries is 700, and mine usually come in at around 685.)

Many writers have told me they find it difficult to write stories that short. My response is that it's just a different process. I think some of the things you can do to make those little mini-mysteries easier to write are: (1) use a lot of dialogue, (2) cut way back on description and exposition, and (3) consider creating series characters that allow you to get right into the plot without a need for backstory. My latest and 79th story to appear in WW (it's in the current, July 25 issue) is one of a series I've been writing for them since 2001.

Remember too that stories that short are rarely profound, meaning-of-life tales. There's simply not enough space for deep characterization or complex plotting or life-changing messages. They seem to work best when the goal is a quick dose of entertainment and humor.

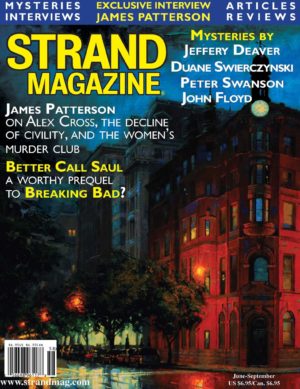

I should mention that writing very short fiction doesn't mean you can't keep writing longer stories also. To be honest, most of my stories lately fall into the 4K-to-10K range. My story in this year's Bouchercon anthology is 5000 words, the one in an upcoming Coast to Coast P.I. anthology is about 6500, and my story in Mississippi Noir (from Akashic Books, to be released in August 2016) clocks in at 10,000. Magazinewise, I've had recent stories in EQMM and Strand Magazine of 7500 and 8000 words, respectively, and my story in the current issue of the Strand (June-September 2016, shown here) is around 4500. (NOTE: As we are all aware, publication is an iffy thing at best, and I'm not implying that everything I write, short or long, makes it into print. It doesn't. But I'm a firm believer that the practice you get writing short shorts can help improve your longer tales as well. It certainly teaches you not to waste words. Besides, it's all fiction; some stories just take longer to tell.)

I should mention that writing very short fiction doesn't mean you can't keep writing longer stories also. To be honest, most of my stories lately fall into the 4K-to-10K range. My story in this year's Bouchercon anthology is 5000 words, the one in an upcoming Coast to Coast P.I. anthology is about 6500, and my story in Mississippi Noir (from Akashic Books, to be released in August 2016) clocks in at 10,000. Magazinewise, I've had recent stories in EQMM and Strand Magazine of 7500 and 8000 words, respectively, and my story in the current issue of the Strand (June-September 2016, shown here) is around 4500. (NOTE: As we are all aware, publication is an iffy thing at best, and I'm not implying that everything I write, short or long, makes it into print. It doesn't. But I'm a firm believer that the practice you get writing short shorts can help improve your longer tales as well. It certainly teaches you not to waste words. Besides, it's all fiction; some stories just take longer to tell.)

Current Events

As for Woman's World, there have been a couple of significant changes at the magazine that, if you decide to send them a story, you should know about.

First, longtime fiction editor Johnene Granger retired this past January. That's the bad news, because Johnene was wonderful, in every way. The good news is, I also like the new editor, Patricia Gaddis. She's smart, professional, and a pleasure to work with.

Second, WW recently changed over to an electronic submission system. As we've already seen at AHMM and EQMM, this makes it far easier for writers to send in their work. I'm not at all sure it makes it easier for editors--emailed submissions always means more submissions, which means more manuscripts to read--but that's another matter, for another coiumn.

Questions

To those of you who write short fiction: Do you find that you gravitate toward a certain length or a certain range? Are you more comfortable with a long wordcount that leaves you room to move around in, or do you like writing shorter, punchier stories? Does the genre matter, in terms of length? Do you already have certain markets in mind when you write a story, or do you prefer to write the piece regardless of length and genre and only then focus on finding a place to which you might submit it? Do those of you who are novelists find a certain pleasure in occasionally creating short stories? When you do, how short are they? Have any of you tried writing "short shorts"? Has anyone sent a story (mystery or romance) to Woman's World?

Final question: In the Not-So-Current Events department, are any of you old enough to remember that "I like short shorts" was a line from Sheb Wooley's "Flying Purple People Eater"?

Unfortunately, I am …

Figures and statistics

Although I've been writing stories for Woman's World for seventeen years now, 50 of those 80 sales have happened since 2010, and I think that's because I have gradually become more comfortable with the task of telling a complete story in less than a thousand words--what some refer to as a short short. (At WW, the max wordcount for mysteries is 700, and mine usually come in at around 685.)

Many writers have told me they find it difficult to write stories that short. My response is that it's just a different process. I think some of the things you can do to make those little mini-mysteries easier to write are: (1) use a lot of dialogue, (2) cut way back on description and exposition, and (3) consider creating series characters that allow you to get right into the plot without a need for backstory. My latest and 79th story to appear in WW (it's in the current, July 25 issue) is one of a series I've been writing for them since 2001.

Remember too that stories that short are rarely profound, meaning-of-life tales. There's simply not enough space for deep characterization or complex plotting or life-changing messages. They seem to work best when the goal is a quick dose of entertainment and humor.

I should mention that writing very short fiction doesn't mean you can't keep writing longer stories also. To be honest, most of my stories lately fall into the 4K-to-10K range. My story in this year's Bouchercon anthology is 5000 words, the one in an upcoming Coast to Coast P.I. anthology is about 6500, and my story in Mississippi Noir (from Akashic Books, to be released in August 2016) clocks in at 10,000. Magazinewise, I've had recent stories in EQMM and Strand Magazine of 7500 and 8000 words, respectively, and my story in the current issue of the Strand (June-September 2016, shown here) is around 4500. (NOTE: As we are all aware, publication is an iffy thing at best, and I'm not implying that everything I write, short or long, makes it into print. It doesn't. But I'm a firm believer that the practice you get writing short shorts can help improve your longer tales as well. It certainly teaches you not to waste words. Besides, it's all fiction; some stories just take longer to tell.)

I should mention that writing very short fiction doesn't mean you can't keep writing longer stories also. To be honest, most of my stories lately fall into the 4K-to-10K range. My story in this year's Bouchercon anthology is 5000 words, the one in an upcoming Coast to Coast P.I. anthology is about 6500, and my story in Mississippi Noir (from Akashic Books, to be released in August 2016) clocks in at 10,000. Magazinewise, I've had recent stories in EQMM and Strand Magazine of 7500 and 8000 words, respectively, and my story in the current issue of the Strand (June-September 2016, shown here) is around 4500. (NOTE: As we are all aware, publication is an iffy thing at best, and I'm not implying that everything I write, short or long, makes it into print. It doesn't. But I'm a firm believer that the practice you get writing short shorts can help improve your longer tales as well. It certainly teaches you not to waste words. Besides, it's all fiction; some stories just take longer to tell.)Current Events

As for Woman's World, there have been a couple of significant changes at the magazine that, if you decide to send them a story, you should know about.

First, longtime fiction editor Johnene Granger retired this past January. That's the bad news, because Johnene was wonderful, in every way. The good news is, I also like the new editor, Patricia Gaddis. She's smart, professional, and a pleasure to work with.

Second, WW recently changed over to an electronic submission system. As we've already seen at AHMM and EQMM, this makes it far easier for writers to send in their work. I'm not at all sure it makes it easier for editors--emailed submissions always means more submissions, which means more manuscripts to read--but that's another matter, for another coiumn.

Questions

To those of you who write short fiction: Do you find that you gravitate toward a certain length or a certain range? Are you more comfortable with a long wordcount that leaves you room to move around in, or do you like writing shorter, punchier stories? Does the genre matter, in terms of length? Do you already have certain markets in mind when you write a story, or do you prefer to write the piece regardless of length and genre and only then focus on finding a place to which you might submit it? Do those of you who are novelists find a certain pleasure in occasionally creating short stories? When you do, how short are they? Have any of you tried writing "short shorts"? Has anyone sent a story (mystery or romance) to Woman's World?

Final question: In the Not-So-Current Events department, are any of you old enough to remember that "I like short shorts" was a line from Sheb Wooley's "Flying Purple People Eater"?

Unfortunately, I am …

Labels:

flash fiction,

Floyd,

short stories,

Woman's World

07 April 2016

Illustrated Mayhem

by Janice Law

by Janice Law

by Janice LawIt was a great grief to me when, sometime between the late ’50’s and the ’70’s, publishers stopped illustrating adult fiction. Not that illustrations for adults ever rivaled the glories of children’s books. Forget the full color splendors for volumes like Treasure Island created by N.A. Wyeth or the marvelous line of John Tenniel’s pictures for Alice in Wonderland.

Just the same, quality novels often had line drawings to enliven the blocks of text which too often today are set up tight to save paper or, in the case of certain popular authors, given ludicrous amounts of spacing and giant margins in order to create a “big” book. Would we had pictures with either or both!

For a time in the ’80’s the lack of illustrations was to some extent compensated for by the care and technical skill of cover art. The book jackets Houghton Mifflin supplied for my first four Anna Peters novels, had beautifully wrought and realistic collage paintings, done by hand, mind you, not on the computer. And this for what were definitely ‘mid-list’ novels. Those jackets, too have gone by the board.

For a time in the ’80’s the lack of illustrations was to some extent compensated for by the care and technical skill of cover art. The book jackets Houghton Mifflin supplied for my first four Anna Peters novels, had beautifully wrought and realistic collage paintings, done by hand, mind you, not on the computer. And this for what were definitely ‘mid-list’ novels. Those jackets, too have gone by the board.I’ve been thinking about illustrations, especially illustrations for mystery novels and stories, because during a dry spell in painting, I did covers and illustrations for two little three-story collections. I wanted to learn how to put up ebooks, and thought that three mystery short stories (originally published in Alfred Hitchcock and Sherlock) and three stories of the uncanny (two unpublished, one in the old Fantasy Book, would make good test projects.

Thanks to the kindness of a very patient techie somewhere in Texas, The Double, (the mysteries) and The Man Who Met the Elf Queen are now available for 99¢ from iBooks. The Elf Queen book has chapter illustrations, too. Thus ends the commercial!

All the illustrations were done freehand on my Wacom drawing slate with an electronic pencil. Not everyone likes the process: basically one holds the pad in one hand and “draws” on the white surface with the pen, producing lines over on the computer screen. A certain ability to disassociate is probably helpful, but I like it a lot, because it is easy to combine line with perfect flat areas of color, flowed in via an icon that looks like a bucket.

The only caveat is that enclosed areas must be perfectly enclosed. Even one pixel missing and the flowed color swamps the entire image. Thankfully, there is an Undo button, and even for someone who is not neat and tidy, the bucket tool enables the creation of perfect flat ‘print like’ areas of color.

The only caveat is that enclosed areas must be perfectly enclosed. Even one pixel missing and the flowed color swamps the entire image. Thankfully, there is an Undo button, and even for someone who is not neat and tidy, the bucket tool enables the creation of perfect flat ‘print like’ areas of color. So much for technique.

The bigger problem for the non-professional is, I think, consistency of image. It is not too hard to produce an attractive illustration. What is difficult is making a character look recognizably the same in different settings and from different angles.

Similarly, the Magus in The Potion of the Empress had dark eyes in print, unsurprising as he was an ancient Roman. However, both an older drawing done in an early Apple graphic program, and my new color version, gave him a chilly light eye, very necessary given the shadows that formed his background.

Similarly, the Magus in The Potion of the Empress had dark eyes in print, unsurprising as he was an ancient Roman. However, both an older drawing done in an early Apple graphic program, and my new color version, gave him a chilly light eye, very necessary given the shadows that formed his background.If nothing else, trying to devise pictures for these little web books has given me sympathy for the illustrators at AHMM who have been illustrating my Madame Selina stories. Do they fit my ideas of the medium and her assistant? Usually not, or not entirely, but they are none the worse for that, being appropriate in size and pattern and style for the magazine and all different, too, which is really interesting.

Just the same, I thought I’d try my hand at both her and Nip and was pleased with the results, but I know better than to attempt a series of panels where I need to keep their features and expressions consistent. Amateur drawings can be lovely but the graphic novel – or even illustrations for a series – are best left to the pros.

Labels:

illustrations,

Janice Law,

John Tenniel,

N.C. Wyeth,

short stories

Location:

Hampton, CT, USA

19 March 2016

Let's Hear It for MMs

by John Floyd

No, not mss (the plural of "manuscript"). MMs (the plural of "mystery magazine"). In fact, let's hear it for MM mss.

Several years ago I was Googling markets for short mystery stories (I do that from time to time) and stumbled upon a site called, believe it or not, Better Holmes and Gardens. When I investigated, I found submission guidelines for a publication I hadn't heard of before: Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine. That's right--yet another MM.

Like all mystery writers, I love AHMM and EQMM, and I also submit a lot of stories to other current magazines that regularly feature mystery fiction, like The Strand, Woman's World, Over My Dead Body, Crimespree, Mysterical-E, BJ Bourg's Flash Bang Mysteries, etc. But the truth is, there aren't a lot of markets out there anymore--paying or non-paying--that specialize in mystery shorts.

Holmes Sweet Holmes

Back to my discovery. Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine is a product of Wildside Press, which I believe also publishes the iconic Weird Tales. As soon as I found SHMM I sent them a story, a little mystery called "Traveling Light," and was pleased and surprised when they accepted it. They paid me promptly, and when the piece was published they mailed me several copies of what turned out to be a smart-looking magazine, with an attractive cover and a wealth of interesting stories inside. Since then they've been kind enough to publish four more of my mysteries, all of them installments in a series featuring a female sheriff and her crime-solving mother.

Back to my discovery. Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine is a product of Wildside Press, which I believe also publishes the iconic Weird Tales. As soon as I found SHMM I sent them a story, a little mystery called "Traveling Light," and was pleased and surprised when they accepted it. They paid me promptly, and when the piece was published they mailed me several copies of what turned out to be a smart-looking magazine, with an attractive cover and a wealth of interesting stories inside. Since then they've been kind enough to publish four more of my mysteries, all of them installments in a series featuring a female sheriff and her crime-solving mother.

My latest is in Issue #19, and appears alongside tales by my friend Jacqueline Seewald and my fellow SleuthSayer Janice Law. I've not yet read all the stories in the issue, but I've read Jacqueline's ("The Letter of the Law") and Janice's ("A Business Proposition") and they're excellent as usual.

Anytime mystery magazines are the topic, I find myself thinking about those that have come and gone, over the years. A few were receptive to my stories and a few rejected everything I sent them (sort of like some of the magazines that are still around), but I think I tried them all. And I thought it might be fun to take a quick trip down MM-memory lane:

Mystery mags of the past

- Murderous Intent Mystery Magazine -- One of my favorites. Margo Power, editor.

- Crimestalker Casebook -- Andrew McAleer, editor. Boston-based.

- Mystery Time -- a small but wonderful little magazine. Linda Hutton, editor.

- Blue Murder -- I think I remember trying these folks and getting rejected every time.

- Red Herring Mystery Magazine -- RHMM published two of my stories, accepted another, and disappeared.

- Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine -- Sadly, before my time.

- Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine -- Sadly, before my time.

- Mouth Full of Bullets -- BJ Bourg, editor. Loved this magazine.

- Whispering Willows Mystery Magazine -- Short-lived. I barely remember this one.

- Heist Magazine -- Australian, featured stories only on CD-ROM.

- Crime and Suspense -- This had some fine stories during its short run. Tony Burton, editor.

- Nefarious -- Online-only, if I remember correctly. One of the first e-zines.

- Black Mask -- Again, before my time.

- Raconteur -- Like RHMM, this one accepted one of my stories and then put all four feet in the air.

- Detective Mystery Stories -- Print publication, editors Tom and Ginger Johnson.

- Orchard Press Mysteries -- This was an early e-zine as well. I had only one story there.

- The Rex Stout Journal -- Another short-lived print magazine.

- Futures -- Babs Lakey, editor. Later became Futures Mysterious Anthology Magazine.

NOTE: Please let me know if you remember some of the many that I've overlooked--or if any of these I've listed have taken on new life.

Square pegs, round holes

Besides the obvious choices, I also continue to try to sell my mystery/crime shorts to places that don't specialize in mysteries but that occasionally publish them anyway--and there are more of those than one might think. Here are some, from both now and long ago: Grit, Dogwood Tales, Spinetingler Magazine, Untreed Reads, Writers on the River, Yellow Sticky Notes, Prairie Times, Mindprints, Sniplits, Pages of Stories, Amazon Shorts, Just a Moment, Kings River Life, Reader's Break, Writers' Post Journal, Short Stuff for Grownups, Champagne Shivers, and The Saturday Evening Post. (Remember, it's generally accepted that a mystery is any story in which a crime is central to the plot. It doesn't have to be a whodunit.)

Besides the obvious choices, I also continue to try to sell my mystery/crime shorts to places that don't specialize in mysteries but that occasionally publish them anyway--and there are more of those than one might think. Here are some, from both now and long ago: Grit, Dogwood Tales, Spinetingler Magazine, Untreed Reads, Writers on the River, Yellow Sticky Notes, Prairie Times, Mindprints, Sniplits, Pages of Stories, Amazon Shorts, Just a Moment, Kings River Life, Reader's Break, Writers' Post Journal, Short Stuff for Grownups, Champagne Shivers, and The Saturday Evening Post. (Remember, it's generally accepted that a mystery is any story in which a crime is central to the plot. It doesn't have to be a whodunit.)

Now and then, even so-called literary magazines will feature a mystery story: Pleiades, Thema, Glimmer Train, Phoebe, some of the college lit journals, etc. Tom Franklin's short story "Poachers," which won an Edgar and appeared in The Best American Mystery Stories 1999, was first published in The Texas Review.

Anthopology

Finally, any discussion of mystery markets should include a mention of anthologies. I usually find them by Googling "anthology calls for submission" and checking Ralan's Webstravaganza, which is advertised as a science-fiction site but doesn't limit itself to that. The two advantages of anthologies over magazines, I think, are that (1) anthos usually request submissions in a fixed window of time, which can be a plus if you hop in right away, and (2) they are often "themed." If you happen to have a finished story that fits their theme--or can write one quickly--you'll already have a leg up on the competition. Another excellent site to check, for mags as well as anthos, is Sandra Seamans's My Little Corner.

Anthologies that I've been associated with, all of which contained some mystery stories and most of which you've never heard of, include Seven by Seven, Trust and Treachery, Magnolia Blossoms and Afternoon Tales, After Death, Flash and Bang, Crime and Suspense I, Mad Dogs and Moonshine, The Gift of Murder, Quakes and Storms, Short Tales, Fireflies in Fruit Jars, Sweet Tea and Afternoon Tales, Ten for Ten, Thou Shalt Not, A Criminal Brief Christmas, Rocking Chairs and Afternoon Tales, and Short Attention Span Mysteries.

Anthologies that I've been associated with, all of which contained some mystery stories and most of which you've never heard of, include Seven by Seven, Trust and Treachery, Magnolia Blossoms and Afternoon Tales, After Death, Flash and Bang, Crime and Suspense I, Mad Dogs and Moonshine, The Gift of Murder, Quakes and Storms, Short Tales, Fireflies in Fruit Jars, Sweet Tea and Afternoon Tales, Ten for Ten, Thou Shalt Not, A Criminal Brief Christmas, Rocking Chairs and Afternoon Tales, and Short Attention Span Mysteries.

A leading anthology for mystery writers is of course the "noir" series produced by Akashic Books, in Brooklyn. Several of my SleuthSayers colleagues have graced those pages, and one of my stories will be in the upcoming Mississippi Noir. Other anthology possibilities are the annual "best of" editions that feature stories published during the previous year, like Otto Penzler's Best American Mystery Stories series.

And that's it--I'm out of examples. I'll end with a question: What are some of your favorite short mystery markets, past and present?

May the ones we have now last forever.

Several years ago I was Googling markets for short mystery stories (I do that from time to time) and stumbled upon a site called, believe it or not, Better Holmes and Gardens. When I investigated, I found submission guidelines for a publication I hadn't heard of before: Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine. That's right--yet another MM.

Like all mystery writers, I love AHMM and EQMM, and I also submit a lot of stories to other current magazines that regularly feature mystery fiction, like The Strand, Woman's World, Over My Dead Body, Crimespree, Mysterical-E, BJ Bourg's Flash Bang Mysteries, etc. But the truth is, there aren't a lot of markets out there anymore--paying or non-paying--that specialize in mystery shorts.

Holmes Sweet Holmes

Back to my discovery. Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine is a product of Wildside Press, which I believe also publishes the iconic Weird Tales. As soon as I found SHMM I sent them a story, a little mystery called "Traveling Light," and was pleased and surprised when they accepted it. They paid me promptly, and when the piece was published they mailed me several copies of what turned out to be a smart-looking magazine, with an attractive cover and a wealth of interesting stories inside. Since then they've been kind enough to publish four more of my mysteries, all of them installments in a series featuring a female sheriff and her crime-solving mother.

Back to my discovery. Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine is a product of Wildside Press, which I believe also publishes the iconic Weird Tales. As soon as I found SHMM I sent them a story, a little mystery called "Traveling Light," and was pleased and surprised when they accepted it. They paid me promptly, and when the piece was published they mailed me several copies of what turned out to be a smart-looking magazine, with an attractive cover and a wealth of interesting stories inside. Since then they've been kind enough to publish four more of my mysteries, all of them installments in a series featuring a female sheriff and her crime-solving mother.My latest is in Issue #19, and appears alongside tales by my friend Jacqueline Seewald and my fellow SleuthSayer Janice Law. I've not yet read all the stories in the issue, but I've read Jacqueline's ("The Letter of the Law") and Janice's ("A Business Proposition") and they're excellent as usual.

Anytime mystery magazines are the topic, I find myself thinking about those that have come and gone, over the years. A few were receptive to my stories and a few rejected everything I sent them (sort of like some of the magazines that are still around), but I think I tried them all. And I thought it might be fun to take a quick trip down MM-memory lane:

Mystery mags of the past

- Murderous Intent Mystery Magazine -- One of my favorites. Margo Power, editor.

- Crimestalker Casebook -- Andrew McAleer, editor. Boston-based.

- Mystery Time -- a small but wonderful little magazine. Linda Hutton, editor.

- Blue Murder -- I think I remember trying these folks and getting rejected every time.

- Red Herring Mystery Magazine -- RHMM published two of my stories, accepted another, and disappeared.

- Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine -- Sadly, before my time.

- Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine -- Sadly, before my time.- Mouth Full of Bullets -- BJ Bourg, editor. Loved this magazine.

- Whispering Willows Mystery Magazine -- Short-lived. I barely remember this one.

- Heist Magazine -- Australian, featured stories only on CD-ROM.

- Crime and Suspense -- This had some fine stories during its short run. Tony Burton, editor.

- Nefarious -- Online-only, if I remember correctly. One of the first e-zines.

- Black Mask -- Again, before my time.

- Detective Mystery Stories -- Print publication, editors Tom and Ginger Johnson.

- Orchard Press Mysteries -- This was an early e-zine as well. I had only one story there.

- The Rex Stout Journal -- Another short-lived print magazine.

NOTE: Please let me know if you remember some of the many that I've overlooked--or if any of these I've listed have taken on new life.

Square pegs, round holes

Besides the obvious choices, I also continue to try to sell my mystery/crime shorts to places that don't specialize in mysteries but that occasionally publish them anyway--and there are more of those than one might think. Here are some, from both now and long ago: Grit, Dogwood Tales, Spinetingler Magazine, Untreed Reads, Writers on the River, Yellow Sticky Notes, Prairie Times, Mindprints, Sniplits, Pages of Stories, Amazon Shorts, Just a Moment, Kings River Life, Reader's Break, Writers' Post Journal, Short Stuff for Grownups, Champagne Shivers, and The Saturday Evening Post. (Remember, it's generally accepted that a mystery is any story in which a crime is central to the plot. It doesn't have to be a whodunit.)